Psychosocial Factors Affecting the Use of Mammography Testing for Breast Cancer Susceptibility: An Eight-Month Follow-Up Study in a Middle-Aged Japanese Woman Sample ()

1. Introduction

In 1994, the age-standardized incidence of breast cancer was greater than any other body region in Japanese women. The incidence rate of breast cancer is increasing every year, and about 50,000 women were diagnosed with and 12,731 women died of breast cancer in 2011 alone [1].

In Japan, as well as in other developed countries, breast cancer is one of the most common causes of death among women. To reduce these fatalities, preventive interventions based on validated research are expected. In the United States, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [2] demonstrated that a 7% - 23% reduction of breast cancer mortality rates was noticed in women aged 40 - 49 years who underwent a screening mammography. Another study [3] indicated that mammography decreases cancer-related mortality by 20% - 30% in women aged 50 - 69 years. Recently, based on a systematic review of evidence, the US Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF 2009) [4] released a new recommendation for women to begin a routine mammography screening biennially, from the age of 50 through 74. The new recommendation contrasts with their previous version, USPSTF 2002 [5], which suggested a screening every 1 - 2 years from the age of 40. However, the USPSTF 2009 had to face a number of oppositions [6-9]and a contentious debate followed. For example, there is a set of strong evidence showing the long-term positive effect of the mammography screening in lowering the mortality rate of breast cancer [6,7].

In Japan, some researchers [10-12] have suggested that mammography is an empirically supported method to decrease the relative risk of breast cancer mortality. At 2005, Japan’s national guidelines for utilizing mammography recommended that women aged over 40 years should use mammography once every year or two [13]. In addition, there is no empirical study to disprove the efficacy of mammography and the national guidelines have been succeeded till the present. However, the annual rate of utilization of mammography has continued about 20% in Japanese women aged over 40 years [14]. This rate is surprisingly low compared to the average rate of usage by middle-aged women living in Western countries, which is about 60% - 80% [11,15].

Psychosocial factors affecting mammography usage for breast cancer susceptibility have been empirically explored for a few decades in Western countries. Schuler et al. [3] performed a meta-analysis of 221 English language papers published between 1998 and 2007. He found several social factors that strongly predict women’s mammography usage: 1) access to a physician, 2) physician’s recommendation of annual mammogramphy testing, 3) past screening behavior, and 4) personal history of breast disease. In addition, McCaul, Branstetter, Shroader, and Grasgow [16] also indicated the presence of a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer.

The Common-Sense Model of self-regulation (CSM) presented by Leventhal, Brissette, and Leventhal [17] is a noteworthy theory because it has been applied to the enactment of health and illness behavior since about 40 years ago. Fundamental features of CSM (Parallel Processing Model: PPM) posit that health threats prompt emotional states of fear and distress and that there is a corresponding need for procedures to manage these emotions (fear control), as well as a cognitive representation of the threat and a corresponding need for procedures to manage the threat (danger control). Fear control and danger control referred to the parallel actions that people undertake and appraise for efficacy in reducing the negative emotions evoked by health threats (fear control) and reducing the threats themselves (danger control) [18]. The PPM was subsequently improved to add a cognitive representation of the health threat prompting the health behavior (action plans) based on combined information between illness symptoms and labels (five content domains: identity, cause, timeline, consequences, and cure). That is, the information and knowledge about disease threats within each of the five domains consists of factors such as symptoms and names (identity), expected duration or expected age of onset (timeline), severity of pain and impact on life functions (consequences), infection or genes (internal and external causes), and whether the disease was perceived as preventable, curable, or controllable (controllability) [17]. These findings suggest that the cognitive representation of disease and screening itself and emotional responses (e.g., worry) to breast cancer risk would be the critical predictors for middleaged women in the actual usage of mammography.

Several studies applied the PPM to health-related behaviors such as mammography testing usage, breast selfexamination, and genetic testing usage for breast cancer susceptibility. These studies identified key psychological factors mediating such health behaviors as perceived risk meaning cognition about the breast cancer threats and cancer worry meaning arousal affect (e.g., anxiety, fear, or worry) [15,16,19-24].

In Japan, because few studies were conducted in this area, we examined the exploratory efficacy of the PPM in mammography usage with a cross-sectional observation of a non-clinical sample of 243 college-aged women. This study explored how perceived risk and cancer worry affected the college women’s intentions to use mammography testing mediated by beliefs about mammography (i.e., benefits and distress consequences resulting from mammography testing), and we found that the PPM was applicable to Japanese women sample as well as the previous researches from Western countries [25]. Moreover, the PPM was also applied to a sample of 1319 middle-aged women (40 - 69 years), and we found that the PPM was a useful model for the Japanese middle-aged women. Furthermore, past experience of using mammography was the strongest predictor of the use of mammography testing during the four-month follow-up period [26].

In this study, 1) we continued our longitudinal observations to clarify whether the PPM is useful for the same middle-aged women’s samples [26], adding four more months to form an eight-month period after the baseline, and 2) find factors affecting mammography use by middle-aged women who have not undergone mammography testing. These results will contribute to overcome certain barriers to screening of the middle-aged women and improve the rate of mammography testing conducted in Japan.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

We surveyed 1030 middle-aged women living in all parts of Japan thrice over an eight-month period. The women aged over 40 years were contacted through a Japanese online research company, Macromill, from September 2010 to May 2011. In the baseline period (T1), 1648 women who agreed to consent form participated in this study. Of the 1648 eligible women, 1319 women (80.0%) completed a second survey four months later (T2) and 1030 women (62.5%) completed all three surveys. The last survey (T3) was implemented eight months after the first (T1). The average age of the 1030 women was 49 years (SD = 7.2, range = 40 - 69).

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Kyushu Lutheran College at Kumamoto, Japan, because the first author (Adachi) worked at this college when we planned this research (2010).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Personal information was obtained at T1 through a researcher-designed questionnaire. This information included age, residential area, employment status, marital status, cancer experience, past test usage, and family cancer history (first-degree relatives with breast and/or ovarian cancer).

2.2.2. Risk Perceptions and Cancer Worry

At T1, perceived risk and worry about breast cancer were each assessed with one item extracted from the items originally developed by Cameron & Diefenbach [19]: 1) perceived risk = “How likely do you think is it that, at some point in your life, you will get breast cancer?” and 2) cancer worry = “To what extent are you worried about getting breast cancer?” Each item was rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (almost certain or extreme).

2.2.3. Mammography Testing Beliefs

Based on the Testing Benefits Beliefs Scale (9 items) and Testing Distress Beliefs Scale (6 items) [19], a 6-item questionnaire was constructed for this study to assess participants’ mammography testing beliefs. This questionnaire was included in T1. Three items were extracted from the original Testing Benefits Beliefs Scale and three items from the Testing Distress Beliefs Scale. Exploratory factor analysis (principal component analysis) was conducted for these six items and two factors were specified following the criteria of eigenvalues ≥ 1.00. Together, these two factors accounted for 76.6% of the item variance. We applied a varimax rotation to this initial solution. Factor 1 scored highly on three items from Testing Benefits Beliefs Scale (range = 0.81 - 0.92) and Factor 2 scored highly on three items from Testing Distress Beliefs Scale (range = 0.61 - 0.89). So Factor 1 was identified as a benefits beliefs factor and Factor 2 was identified as a distress beliefs factor. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the three benefits beliefs items and the three distress beliefs items were 0.89 and 0.73, respectively. The main item for benefits beliefs was “Getting this mammography test would help me in planning my future” and for distress beliefs it was “Getting this mammography test would be very frightening”. These items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

In addition, to assess participants’ worry about being showered with radiation and having breast pains during mammography testing, we also designed one item for each: 1) radiation worry = “To what extent are you worried about radiation effects during getting mammography testing?” and 2) pain worry = “To what extent are you worried about breast pains during mammography testing?” These items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extreme) at T1.

2.2.4. Testing Intentions

At all the three surveys, participants were assessed on their intentions to use mammography testing. One item was used based on Cameron & Diefenbach [19]: “Are you planning to use mammography testing regularly for breast cancer susceptibility in the near future?” Responses ranged from 1 (definitely no) to 5 (definitely yes).

2.2.5. Information Seeking about Mammography Testing

To assess participants’ information seeking about mammography testing at times 2 and 3, we designed one item: “Have you sought for information about mammography testing since the dates of the first (second) investigation?” The response was given as a binary yes/no.

2.2.6. Mammography Testing Usage

At T2 and T3, participants were asked to whether they had undergone mammography testing during the fourmonth period following the T1 survey and T2 survey, respectively. The same item was used for each: “Have you used mammography testing since the date of the first (second) investigation?” The response was given as a binary yes/no.

2.2.7. Temperaments

Harm Avoidance (HA) and Reward Dependence (RD) from the Japanese version of the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI, 125 items [27]) were used to assess participants’ temperaments at T1. The Japanese version of the TCI-125, based on the original TCI [28], is a well-validated measure that assesses two aspects of personality: temperament and character. Temperament is assessed along four dimensions: Novelty Seeking, Harm Avoidance, Reward Dependence, and Persistence. Character is assessed along three dimensions: Self-Directedness, Cooperativeness, and Self-Transcendence. Because our previous research indicated that only HA and RD affected one’s perceived risk, cancer worry, and testing beliefs [25], we used two temperament dimensions (HA, RD). For both dimensions, items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 4 (very likely). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for HA and RD in the sample of 1030 women who completed the study were 0.88 and 0.70, respectively.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Three sets of data analyses were conducted to examine two aims using SPSS 11.0 J and Amos 18. First, descriptive data of participants’ demographics was calculated. Second, to examine the first aim, intercorrelations between demographics, psychosocial factors, and women’s mammography usage were calculated and a path analysis setting the outcome variable to mammography testing usage during an eight-month period (T2 and /or T3) following T1 (yes/no) using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted. Third, to examine the second aim, binary logistic analysis setting the outcome variable to the mammography usage during the eight-month follow-up was conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The total number of women was 110 (10.6%) from the Hokkaido or Tohoku areas, 416 (40.4%) from the Kanto area, 152 (14.8%) from the Chubu area, 203 (19.7%) from the Kinki area, 62 (6.3%) from the Chugoku or Shikoku areas, and 87 (8.4%) from Kyushu area. In all, 76.9% were married, 21.2% were working full time, 2.5% had previously been diagnosed with breast and/or ovarian cancer, 7.6% had family (first-degree relative) cancer histories of breast and/or ovarian cancer, and 40% had never undergone mammography testing (Table 1).

3.2. Correlations between Variables

Intercorrelation coefficients were calculated between demographics, TCI HA and RD, perceived risk and cancer worry, mammography testing beliefs, testing intentions, information seeking, and mammography usage (Table 2). Women who used mammography at least once during the eight-month period following baseline were assessed as “yes” (1) and women who did not use it at all were assessed as “no” (0).

Significant correlations with mammography usage (p < 0.05) were employment status (longer time employed), marital status (married), cancer experiences, past mammography testing, high RD, high perceived risk, high cancer worry, low radiation worry, low pain worry, high testing benefits beliefs, low testing distress beliefs, in-

Table 1. Demographics of the participants at baseline.

formation seeking, and high testing intentions. An especially strong correlation was observed between mammography usage and past mammography usage (r = 0.70), and a moderate correlation was observed between mammography usage and intentions (r = 0.51).

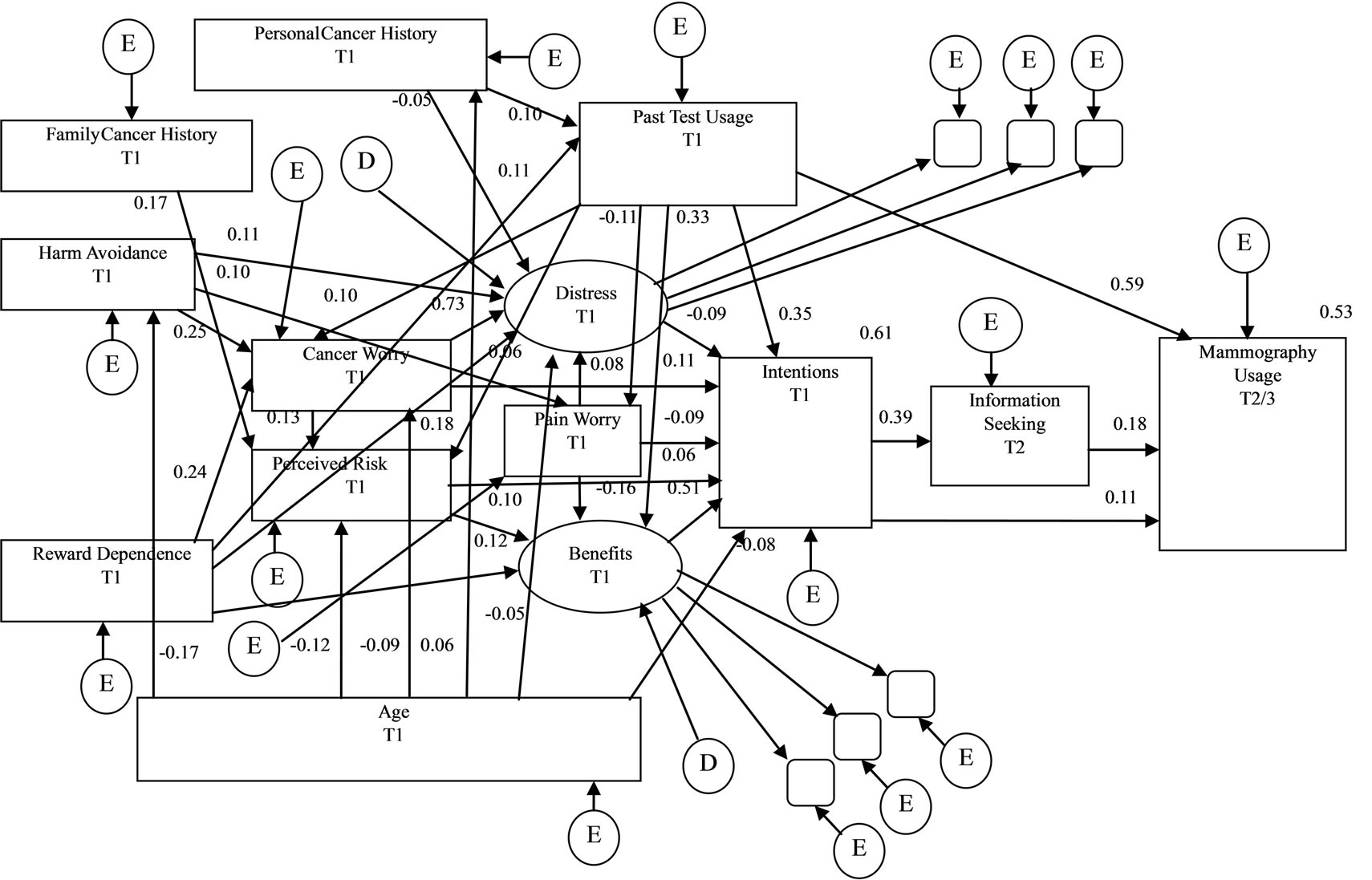

We constructed a path model setting the outcome variable to mammography usage during an eight-month period (T2 and/or T3) and calculated the fitness indices of this model using SEM. We obtained a path model that yielded acceptable fit indices with GFI = 0.949, AGFI = 0.918, CFI = 0.933, and RMSEA = 0.064. This model accounted for 53% of the variance. In this model, the main results were as follows (Figure 1). Mammography usage (T2 and/or T3) were predicted by past mammography usage (T1), high testing intentions for the T1 survey, and information seeking for the T2 survey. Testing intentions were predicted by past mammography usage, younger age, low testing distress beliefs, high testing benefits beliefs, high pain worry, high cancer worry, and high perceived risk for the T1 survey. Cancer worry (T1)

Table 2. Intercorrelations between the demographics, TCI-Harm Avoidance and Reward Dependence, perceived risk, cancer worry, mammography testing belief, intentions to utilize mammography, information seeking, and utilizing mammography.

Figure 1. Observed path model between demographics, perceived risk, cancer worry, mammography beliefs, testing intentions, information seeking, and testing usage during an eight-month period following T1. All standardized structural coefficients are significant (ps < 0.05). T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3, GFI = 0.949, AGFI = 0.918, CFI = 0.933, RMSEA = 0.064.

was predicted by younger age, high HA, and high RD for the T1 survey. Perceived risk (T1) was predicted by younger age, family cancer history, high RD, and high cancer worry for the T1 survey.

3.3. Factors Affecting Mammography Usage in Samples of Middle-Aged Women Who Had Not Undergone Mammography Prior to Study

Of the 1030 middle-aged women, 412 women who answered that they had not undergone any mammography prior to T1 (40%) were analyzed using binary logistic regression model with mammography usage (T2 and/or T3) for the binary outcome measure. The predictor variables were temperament (HA, RD), employment status, cancer experience, family cancer history (first-degree relatives with breast and/or ovarian cancer), perceived risk, cancer worry, radiation worry, pain worry, mammography testing beliefs (benefits, distress), and testing intentions for the T1 survey and information seeking for the T2 survey. The average age of the 412 women was 49 years (SD = 7.7, range = 40 - 69). Of the 412 women, 40 women (9.7%) underwent mammography testing during the eight-month period after the T1 survey. That meant that about 90% women did not use mammography testing eight months later. The demographics of this group did not differ from the trend of the original 1030 women sample.

Outcomes of the binary analysis using logistic regression are presented in Table 3. The model was statistically significant (χ2 = 77.65, df = 15, p < 0.001) and accounted for 36.5% of the variance. Mammography usage was significantly predicted by cancer worry (OR = 1.88; T1), low distress beliefs (OR = 0.71; T1), testing intentions (OR = 2.04; T1), and information seeking (OR = 6.05; T2). In particular, information seeking was associated with a nearly sixfold increase in the likelihood of the mammography usage at T2 and/or T3. No other significant effects were revealed.

In additional analysis using 1030 women data at T1, we found that women who did not have any mammography experience had significantly lower beneficial beliefs about mammography than the women had mammography in the past (inexperienced women: Mean = 9.07, SD = 3.00, n = 412; experienced women: Mean = 11.12, SD = 2.69, n = 618; t = 11.46, df = 813.78, p < 0.001) and higher distress beliefs about it than the women who got it (inexperienced women: Mean = 8.98, SD = 3.12, n = 412; experienced women: Mean = 8.14, SD = 2.85, n = 618; t = 4.35, df = 827.20, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study primarily aimed at examining the adequacy of

Table 3. Binary logistic regression for mammography usage in women who had not undergone mammography testing at baseline survey (n = 412).

the PPM in middle-aged women living in all parts of Japan and to find factors affecting mammography usage within the eight-month follow-up in 412 women who had not yet undergone any mammography testing. Consistent with our previous researches [25,26], perceived risk and cancer worry affected intentions to use mammography directly and/or mediated by mammography testing beliefs during the eight-month follow-up period. Furthermore, intentions also had the direct effect of promoting mammography screening behaviors. These results support the idea that the PPM is an applicable model that explains the mechanism of health-related behaviors such as mammography usage in Japan as well as in Western countries [e.g., 15]. In addition, 40% of middle-aged women who had not undergone mammography tended to use mammography when they had greater cancer worry, fewer distress beliefs about mammography testing, more testing intentions, and were more information seeking.

Based on the Figure 1, beneficial beliefs about mammography were the most important mediation variable affecting the intentions to use mammography. This variable was facilitated by past mammography usage, high perceived risk, and high RD, but reduced by high pain worry. On the other hand, women who did not have any mammography experience had significantly lower beneficial beliefs about mammography than the women had mammography in the past and higher distress beliefs about it than the women who got it. These results may indicate that women who have not undergone mammography don’t have enough information about testing and breast cancer because of their being based inexperienced. Furthermore this information seeking behavior is strongly associated with the likelihood of mammography usage, as indicated in Table 3. Schueler et al. [3] suggested that women who were more interested in and knowledgeable about preventive examination (e.g., mammography) were able to overcome certain barriers to screening. Aiken, West, Woodward, Reno, and Reynolds [29] reported the role of information about breast cancer prevalence rates, risk factors, and the effectiveness of mammography for early detection in middle-aged asymptomatic women. In this report, women who had received information and became more knowledgeable about breast cancer and mammography, perceived the benefits of mammography and formed intentions to use mammography. These trends are linked to behaviors of obtaining mammography.

Therefore, to improve the rate of mammography conducted, we need to give accurate information about mammography (e.g. its effectiveness in reducing breast cancer mortality, testing procedures) and breast cancer (e.g., its incidence rate, mortality rate, prognosis, treatment methods) to middle-aged women.

Consistent with results of a meta-analysis [3], past mammography usage was the strongest predictor of the use of mammography. In our analysis, 572 middle-aged women (92.5%), who had undergone mammography testing, repeated it during the next eight-month period. However, only 40 women (9.7%) who had not undergone mammography testing completed in the same period. This result also suggests that the first-usage of mammography testing will encourage middle-aged women to undergo repeated mammography.

Certainly, the use of mammography screening for early detection of breast cancer is still a controversial subject. Sharpe et al. [8] suggest, however, that the longer effect of the new recommendation remains to be seen. They also note that after the USPSTF recommenddations were issued in late 2009, the abrupt decrease in the use of screening mammography in 2010 was observed.

While this study shows very promising results, there are several limitations. First, the follow-up period was only eight months. Japan’s national guidelines for breast cancer testing recommend that women aged over 40 years use mammography testing once every year or two [13]. Different results might be observed when lengthening the follow-up period to conform to Japan’s guidelines. Second, the contents of the information that predicted the middle-aged Japanese women’s mammography usage at the eight-month period were not considered. Five domains of cognitive representation (identity, cause, timeline, consequences, and cure) produced different types of health-related behavior in the CSM theory [17]. To construct more effective programs for facilitating mammography usage, we need to conduct further studies that include these five domains.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23653216 (main researcher: Keiichiro Adachi). The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.