Preliminary Palynostratigraphic Data on the Middle Albian-Lower Cenomanian of the Tarfaya Basin, Southwest Morocco ()

1. Introduction

The Northwestern African continental margin, particularly the Moroccan Atlantic margin, is among the oldest passive continental margins [1] . They have been of particular interest for oil exploration, as oil and/or gas shows have been recorded in most of the drilled wells (unpublished reports, ONHYM, 1999, 2000). The sedimentary deposits in the Tarfaya-Laayoune-Boujdour basin are Mesozoic and Cenozoic, overlying crystalline rocks of Proterozoic and Paleozoic age [2] [3] [4] .

The geological evolution of the Tarfaya, Laayoune, Boujdour sedimentary basin is linked with the geological history of the African craton and the opening of the Atlantic. This opening resulted in a major accident (the Zemmour fault, following the separation to the East of the Anti-Atlas massif and the Tindouf basin). On the other hand, it was led by the establishment of sediments rich in organic matter, which allowed the installation of many oil basins, precisely in the estuaries, at larger depths of burial.

To achieve a better assessment of the sedimentary formations making up a petroleum system, several sedimentological, biostratigraphic, geochemical, geophysical and micropalaeontological approaches have been carried out since the 90’s [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] .

Albian-Cenomanian palynology is poorly developed on the Moroccan Atlantic margin, except for the work of [10] and [11] . On the other hand, previous work concerning this interval is well developed in the northern and central Atlantic [12] - [17] .

Palynostratigraphic studies realized in the Tarfaya-Laayoune-Boujdour basin are rare, punctual and limited to subsurface data. Those carried out on the Upper Cretaceous deposits include the Cenomanian-Turonian [6] [7] and the Upper Cenomanian-Coniacian [8] . However, studies on the upper Albian-lower Cenomanian transition are rare, which makes this work important and complementary. The identification of stratigraphic taxa importance from this study will permit establishing a refined and precise biostratigraphic data of the Albian-Cenomanian interval in Moroccan basins, particularly in the Tarfaya_Laayoune_Boujdour basin.

The present work was proposed by the National Office of Hydrocarbons and Mining, it aims to create a coherent biostratigraphic framework of the 3404 m to 3408.5 m interval from FD.1 well located in the offshore of the Tarfaya_Laayoune_Boujdour basin.

2. Geographic and Geological Setting for Southwest Morocco

The Tarfaya Laayoune Boujdour basin in Southwest Morocco stretches along the coast in the south of Morocco between 28˚N and 24˚S. Its depending on the definition of its southern margin and whether its offshore extent is taken into account. It is bounded to the south by the Mauritanides, to the north by the Anti-Atlas, to the east by the Reguibats and to the west by the Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1). Extending parallel to the coast in a NNE. SSW, most of it lies in the

![]()

Figure 1. Geological maps of the Moroccan Sahara showing the location of the studied Well [FD-1], after [37] .

Moroccan Sahara. It has been the subject of several regional geological studies. These include: [18] - [30] .

The evolution of the Tarfaya, Laayoune, Boujdour basin is intimately associated to the geological history of the African craton and the opening of the Atlantic [21] , with the transition from a rift to a marginal basin. This basin was formed during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic in the marine direction of the stable West African craton [31] . The basement is made up of folded Precambrian and Paleozoic rocks unconformably overlain by Mesozoic and Cenozoic sediments. Detailed and comprehensive geological descriptions of this region have been published by: [32] and [26] .

In response to early rifting of the central and southern North Atlantic, and a marine incursion into this rift system during the Triassic, a major phase of evaporite deposition occurred in this region [19] [33] and [31] . Today, this salt province extends along the northwest coast of Morocco, and salt diapirs are important offshore structural features. The Jurassic was initiated by a major marine transgression and was characterized by high subsidence rates, generally offset by thick terrigenous clastic sequences and carbonate platform accumulations in the shallow-water plateau zone. A thick Lower Cretaceous (Aptian-Albian) deltaic sequence accumulated during and after a major global Valanginian regression with sediments probably originating from the Tindouf basin and the African craton to the southeast [34] .

According to Ratschiller [35] , a series of major transgressive cycles in the Upper Cretaceous (Albian/Cenomanian, Cenomanian/Turonian, Santonian/Campanian) caused repeated and extensive flooding of the continental margin of NW Africa and initiated the deposition of over 800 m of laminated biogenic sediments of Cenomanian-Santonian age in the Tarfaya-Laayoune-Boujdour basin. These sediments consist mainly of calcareous nannoplankton, dispersed biogenic silica and planktonic foraminifera, and are high in marine organic matter. Sedimentation rates exceeded 10 cm/ky. The sediments were deposited in a nutrient-rich environment in which an upwelling system developed on an open plateau [36] . During the Miocene, the Upper Cretaceous succession was eroded and the deposition of the relatively thin Moghrebian formation took place.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Material

A total of 10 cutting samples were examined from FD-1 well. The latter is located 25 km from NNW of Tan Tan and 200 km SW of Agadir, offshore Morocco (Lat. 29˚29'53.008"N, Long. 11˚29'47.711"W) (Figure 1).

The interval between 3404 m and 3408.5 m was analyzed to investigate palynological analyses. This interval is predominated by grey to grey-brown sub blocky calcareous claystone. The general preservation of organic matter is good and palynomorphs are therefore abundant.

The latter consists of spores, pollen grain and acritarchs. Dinoflagellate cysts were also available within the studied material in high percentages in comparison with the other palynomorphs. Consequently, age assessment in this work is primarily based on ranges of dinoflagellate cysts.

3.2. Method

The ten samples were made using standard palynological methods [38] . All preparations were carried out in the laboratory of palynology, FSBM, Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco. The first step corresponds in removing contaminants by washing the samples with distilled water and then drying in an oven at 50˚C. The acid attack involves an initial immersion of 40 gramme of rock in HCl (37%) followed by digestion in hot HF (40%) during 48 h and further immersion in hot HCl (20%) to dissolve the carbonate and siliceous contents. After successive washes, the residue is sieved through 15 µm filter mesh to remove some of the fine material, and stained with safranin (C20H19ClN4) to enhance the colors of the palynomorphs. Palynological material is mounted on microscope slides using glycerin jelly. Two slides from each sample were routinely examined under a Leica transmitted light microscope equipped with a digital camera (Leica DFC450C). The palynological slides are stored in the laboratory of palynology, FSBM (Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco) and observed with a light microscope (Leica) Dinoflagellate cyst nomenclature is based on Dinoflaj 3, [39] and [40] . All dinoflagellate cyst taxa identified in this study are listed alphabetically in the species list (Appendix A) and their distribution in the studied well is plotted in Table 1.

4. Palynostratigraphic Results and Discusion

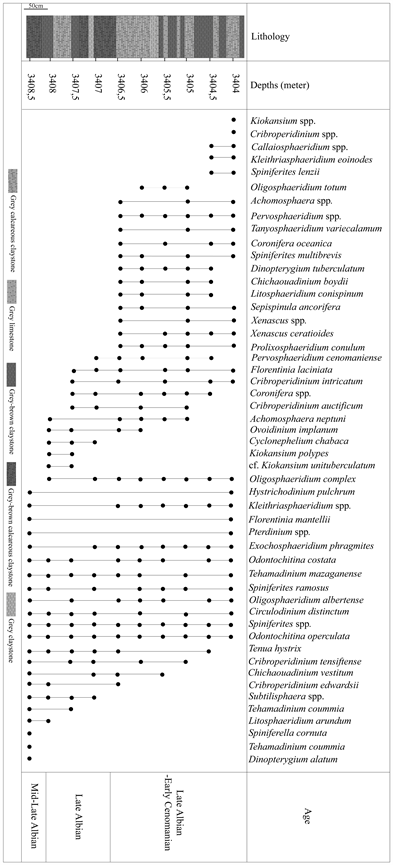

Palynological analysis of the organic matter contained in the studied samples revealed the presence of preserved, diverse and significant palynomorphs dominated by dinoflagellate cysts (81.97%) and sporomorphs (22%). Other marine palynomorphs (foraminiferal test linings, acritarchs and algae) (Plate 1) are rather rare and do not exceed (4.07%) (Figure 2). The vertical stratigraphic distributions of palynomorphs are shown in Table 1. Thus, some forms of dinocysts have been represented in (Plates 2-5).

Age assessment of the studied interval from FD-1 well is based on the first occurrences (Fos) and last occurrences (Los) of marker dinoflagellate cyst species, as well as on the presence of significant species associated with their acme. The listed associations are compared to the upper Albian-lower Cenomanian

![]()

Figure 2. Percentages: dinoflagellate cysts, sporomorphs, foraminifera-Acritarchs and algae, in the studied interval from FD-1 well.

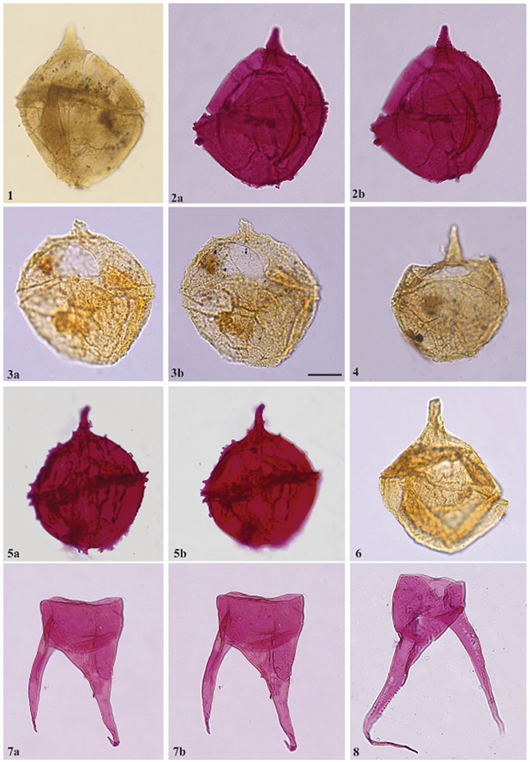

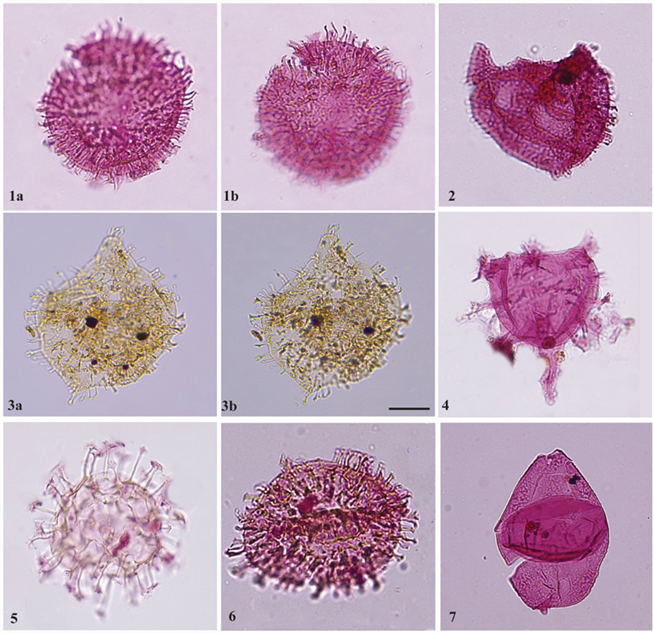

Plate 1. Photo micrographs of palynomorphs from FD-1 well. Scale bar in Fig. 5 represents 20 µm: 1: Classopollis sp. (Sample 3405, slide 1, EF X41.); 2, 3: Gnetaceapolenites jansonii (2 Sample 3408, slide 2, EF M32/3. 3 Sample 3404, slide 2, EF U 47/1.); 4, 5,6: Elaterosporites sp. (4: Sample 3407, 5: Sample 3404, 6 Sample 3407); 7, 10: Phytoclast (Sample 3407, slide 1, EF L33/L34.); 8: Acritarches (Sample 3408, slide 1, EF H44/3.); 9: Leosphaeridia (Sample 3406.5, slide 2, EF R39.); 11: Kiokansium spp. (Sample 3404, slide 1, EF U44); 12: Moa (amorphous organic matter) (Sample 3407, slide 2, EF O40/2).

Plate 2. Dinoflagellate cysts recovered from the FD-1 well. Scale bar in Fig. 3b. represents 20 µm for all specimens: 1a,b: Tehamadinium coummia (Below, 1981a) Jan du Chêne et al., 1986b. (Sample 3408,5, slide 2, EF G50/1.); 2: Spiniferites ramosus (Ehrenberg, 1837b) Mantell, 1854. (Sample 3407, slide 1, EF L41); 3 a,b: Oligosphaeridium albertense (Pocock, 1962) Davey and Williams, 1969. (Sample 3404,5, slide 3, EF U37/4); 4: Oligosphaeridium totum (Brideaux, 1971). (Sample 3405, slide 1, EF V41/2); 5: Oligosphaeridium complex (White, 1842) Davey and Williams, 1966b. (Sample 3405.5, slide 2, EF O43/2). 6 a,b: Coronifera spp. (Sample 3405, slide 2, EF U 43/1.); 7: Callaiosphaeridium spp. (Davey and Williams, 1966b). (Sample 3404.4, slide 1, EF P25.); 8 a,b: Kleithriasphaeridium eoinodes (Eisenack, 1958a). Sarjeant, 1985a (Sample 3404, slide 2, EF X50/1).

Plate 3. Dinoflagellate cysts recovered from the FD-1 well. Scale bar in Fig. 3b. represents 20 µm for all specimens: 1; 2a, b: Cribroperidinium tensiftense (Below, 1981a). (1: Sample 3405, slide 1, EF O29/2. 2a, b: Sample 3407.5, slide 1, EF N45/4.); 3a, b; 4: Cribroperidinium intricatum (Davey, 1969a). (3a, b: Sample 3404,5, slide 2, EF U25. 4: Sample 3407,5, slide 2, EF J55); 5a, b: Cribroperidinium edwardsii (Cookson and Eisenack, 1958) Davey, 1969a. (Sample 3408, slide 2, EF O33/1); 6: Cribroperidinium spp. (Neale and Sarjeant, 1962) Davey, 1969a (Sample 3404, slide 4, EF U27); 7 a, b: Odontochitina operculate (Wetzel, 1933a) Deflandre and Cookson, 1955. (Sample 3408.5, slide 3, EF E29/E30); 8: Odontochitina costata (Alberti, 1961) Clarke and Verdier, 1967 (Sample 3404, 5, slide 2, EF T50).

Plate 4. Dinoflagellate cysts recovered from the FD-1 well. Scale bar in Fig. 3. represents 20 µm for all specimens: 1 a,b: Florentinia mantellii (Davey and Williams, 1966b) Davey and Verdier, 1973. (Sample 3404, slide 1, EF O36/O37); 2 a,b: Florentinia laciniata (Davey and Verdier, 1973). (Sample 3405, slide 1, EF P54/2.); 3: Exochosphaeridium phragmites (Davey et al., 1966). (Sample 3406.5, slide 1, EF K33/K34); 4 a,b, c: Pervosphaeridium cenomaniense (Norvick, 1976) Below, 1982c. (Sample 3407, slide 2, EF V42/4); 5 a,b: Pervosphaeridium spp. (Yun Hyesu, 1981). (Sample 3406, slide3, EF T35/4); 6 a,b: Sepispinula ancorifera (Cookson and Eisenack, 1960a) Islam, 1993. (Sample 3404, slide 1, EF M15/4).

Plate 5. Dinoflagellate cysts recovered from the FD-1 well. Scale bar in Fig. 3b. represents 20 µm for all specimens: 1 a,b: Tenua hystrix (Eisenack, 1958a) Sarjeant, 1985a. (Sample 3404,5, slide 1, EF T46/2); 2: Circulodinium distinctum (Deflandre and Cookson, 1955) Jansonius, 1986. (Sample 3408.5, slide 1, EF Y45); 3 a,b: Circulodinium distinctum (Deflandre and Cookson, 1955) Jansonius, 1986. (Sample 3408, slide 3, EF C35/3); 4: Xenascus spp. Cookson and Eisenack, 1969 (Sample 3406.5, slide 2, EF Q28/1. slide 1, EF H37); 5: Cf. Kiokansium unituberculatum (Tasch et al., 1964) Stover and Evitt, 1978. (Sample 3407.5, slide 1, EF W44/2); 6: Kiokansium spp. (Stover and Evitt, 1978). (Sample 3404, slide 2, EF I47/1. slide 2, EF R50); 7: Ovoidinium implanum (Sample 3406, slide 1, EF V29)

assemblages from contemporary basins in the Atlantic and Tethyan domains (e.g. [10] - [15] [17] [41] - [55] ).

4.1. Mid to upper Albian (3408 - 3408.50 m)

The dinoflagellate cyst association recorded at this depth includes: Litosphaeridium arundum, Chichaouadinium vestitum, Tehamadinium coummia (Plate 2),

Table 1. Vertical distribution of the recorded dinoflagellate cysts in the FD-1 Well, Tarfaya-Laayoune-Boujdour basin, Morocco.

Dinopterygium alatum, Cribroperidinium tensiftense (Plate 3), Spiniferella cornuta and Tehamadinium coummia is known to occur in the middle of the Albian, characterizing the Tehamadinium coummia zone defined in Italy by the FO of Tehamadinium coummia at the base of the zone and the LO of Litosphaeridium arundum. This taxon has also been recorded in the middle and upper Albian period of the EGA.1 well [Agadir basin, SW Morocco] [11] . The Litosphaeridium arundum zone is defined by the FO of Litosphaeridium arundum at its base and the FO of Tehamadinium mazaganense at the top, and marks the middle to upper Albian [56] . In EGA.1 well, the LO of Litosphaeridium arundum coincides with the first appearance [FO] of Tehamadinium mazaganense. In France, it is a marker of the mid- to Upper Albian [43] , middle Albian in DSDP Hole 400 in Australia [44] and upper Albian in the offshore Moroccan site DSDP 545 [10] .

From the above, the depths interval between 3408 m and 3408.50 m could correspond to the middle Albian-upper Albian transition.

4.2. Upper Albian (3406.5 - 3408 m)

Marker taxa occurring throughout this interval include Cyclonephelium chabaca, Cribroperidinium auctificum and Chichaouadinium boydii.

The recognition of the upper Albian is based on the FOs of Cyclonephelium chabaca at the base of this interval, followed by the successive FOs of Cribroperidinium auctificum (depth 3407.50 m) and Chichaouadinium vestitum (depth 3407 m). Cyclonephelium chabaca is considered as a stratigraphic marker of the upper Albian in the Atlantic and Tethyan domains, such as in Libya [57] [58] , in DSDP 627B and DSDP 635B in the Bahamas [13] and in DSDP 547A and DSDP 545 [10] , as well as in EGA.1 well in Morocco [11] . The FO of Cribroperidinium auctificum is recorded in the Upper Albian in Italy [56] and in Morocco in the Agadir basin (EGA.1 well) [11] . The upper part of this interval is defined by the FOs of Chichaouadinium boydii, Litosphaeridium conispinum, Dinopterygium tuberculatum, Sepispinula ancorifera and Xenascus ceratioides. All these findings allowed us to assign the interval between 3406.5 m and 3408 m to the upper Albian.

4.3. Upper Albian_Lower Cenomanian (3404 - 3406.50 m)

In this interval, The Fos of the Sepispinula ancorifera (Plate 4), Chichaouadinium boydii, Litosphaeridium conispinum, Dinopterygium tuberculatum, Prolixosphaeridium conulum and Xenascus ceratioides are recorded at sample 3406.50 m. These taxa have been observed in association with Pervosphaeridium cenomaniense and Cribroperidinium intricatum (Plate 3). Pervosphaeridium cenomaniense (Plate 4) characterize the middle Cretaceous of the offshore Camp Basin, southeastern Brazil [59] and the upper Albian-middle Cenomanian of Atlantic Ocean [60] . Australia’s upper Albian-lower Cenomanian transition is indicated by Sepispinula ancorifera [61] . Litosphaeridium conispinum characterizes the Upper Albian-Lower Cenomanian transition in EGA.1 well, southwest of Morocco [11] and the Upper Albian in DSDP Hole 545 in the offshore of Morocco [10] . It also marks the upper Albian-lower Cenomanian transition in France [62] and in the DSDP Hole 635 on the Atlantic Ocean [13] . Other taxa also occur in this interval and show stratigraphic interest, Xenascus ceratioides is a good marker of the Upper Albian-Lower Cenomanian in England [63] , in Egypt [64] , in Libya [57] [46] and in the southwest of Morocco [10] [11] . Cribroperidinium intricatum is a marker for the Upper Albian-Lower Cenomanian in Atlantic Ocean [65] [13] , in NW Europe [66] [45] and in the Tethyan domain [67] . Dinopterygium tuberculatum characterize the upper Albian-Cenomanian in Australia [68] , in Egypt [69] , in Libya [58] , in Iraq [70] and in southwest of Morocco [10] [11] . Prolixosphaeridium conulum is considered a marker of the Cenomanian in France [66] [71] , in England [72] , in Australia [73] and in Morocco [11] [74] . It characterizes the upper Albian-middle Cenomanian of the Atlantic Ocean [13] and the Upper Albian-Lower Cenomanian of Libya [58] . Therefore, the interval between 3404 m and 3406.5 m may correspond to the Upper Albian-Lower Cenomanian.

4. Conclusion

The interval between 3404 m and 3408.5 m from FD.1 yielded rich and well preserved organic matter dominated by dinoflagellate cysts. Based on the association of dinoflagellate cysts: Cribroperidinium tensiftense, Chichaouadinium vestitum, Tehamadinium coummia, Spiniferella cornuta, Dinopterygium alatum, Litosphaeridium arundum, Cyclonephelium chabaca, Cribroperidinium auctificum, Chichaouadinium boydii, Sepispinula ancorifera, Litosphaeridium conispinum, Dinopterygium tuberculatum, Prolixosphaeridium conulum and Xenascus ceratioides; we assign an age to the studied interval. We assigned depths 3408 m and 3408.5 m to the middle-upper Albian transition. The upper Albian lies between 3406.5 m and 3408 m and the upper Albian-lower Cenomanian is identified between 3404 m and 3406.5 m.

Acknowledgements

We thank ONHYM (Office National des Hydrocarbures et des Mines) Rabat, Morocco for providing the borehole equipment. We would also like to thank the editor of Open Journal of Geology for treating our manuscript. This study is led by T. Hssaida.

Appendix A

Dinocysts species identified in this study and classified alphabetically. Details and references not provided are given in [75] [40] [76] .

Achomosphaera neptuni (Eisenack, 1958a) Davey and Williams, 1966a.

Achomosphaera spp. (Evitt, 1963).

Callaiosphaeridium spp. (Davey and Williams, 1966b).

Cf. Kiokansium unituberculatum (Tasch et al., 1964) Stover and Evitt, 1978.

Chichaouadinium boydii (Morgan, 1975) Bujak and Davies, 1983.

Chichaouadinium vestitum (Brideaux, 1971) Bujak and Davies, 1983.

Circulodinium distinctum (Deflandre and Cookson, 1955) Jansonius, 1986.

Coronifera oceanica (Cookson and Eisenack, 1958) May, 1980.

Coronifera spp. (Cookson and Eisenack, 1958) Davey, 1969a.

Cribroperidinium auctificum (Brideaux, 1971) Stover and Evitt, 1978.

Cribroperidinium edwardsii (Cookson and Eisenack, 1958) Davey, 1969a.

Cribroperidinium intricatum (Davey, 1969a).

Cribroperidinium spp. (Neale and Sarjeant, 1962) Davey, 1969a; Sarjeant, 1982b; Helenes, 1984.

Cribroperidinium tensiftense (Below, 1981a).

Cyclonephelium chabaca (Below, 1981a).

Dinopterygium alatum (Cookson and Eisenack, 1962b) Fensome et al., 2009.

Dinopterygium tuberculatum (Eisenack and Cookson, 1960) Stover and Evitt, 1978.

Exochosphaeridium phragmites (Davey et al., 1966)

Florentinia laciniata (Davey and Verdier, 1973).

Florentinia mantellii (Davey and Williams, 1966b) Davey and Verdier, 1973.

Hystrichodinium pulchrum (Deflandre, 1935)

Kiokansium polypes (Cookson and Eisenack, 1962b) Below, 1982c.

Kiokansium spp. (Stover and Evitt, 1978).

Kleithriasphaeridium eoinodes (Eisenack, 1958a). Sarjeant, 1985a.

Kleithriasphaeridium spp. (Davey, 1974) Torricelli, 2001; Fensome et al., 2009.

Litosphaeridium arundum (Eisenack and Cookson, 1960) Davey, 1979b.

Litosphaeridium conispinum (Davey and Verdier, 1973) Lucas-Clark, 1984.

Odontochitina Costata (Alberti, 1961) Clarke and Verdier, 1967.

Odontochitina operculata (Wetzel, 1933a) Deflandre and Cookson, 1955.

Oligosphaeridium albertense (Pocock, 1962) Davey and Williams, 1969.

Oligosphaeridium complex (White, 1842) Davey and Williams, 1966b.

Oligosphaeridium totum (Brideaux, 1971).

Ovoidinium implanum (Davey, 1979b).

Pervosphaeridium cenomaniense (Norvick, 1976) Below, 1982c.

Pervosphaeridium spp. (Yun Hyesu, 1981).

Prolixosphaeridium conulum (Davey, 1969a).

Pterodinium spp. (Eisenack, 1958a) Yun Hyesu, 1981; Sarjeant, 1985a.

Sepispinula ancorifera (Cookson and Eisenack, 1960a) Islam, 1993.

Spiniferella cornuta (Gerlach, 1961) Stover and Hardenbol, 1994.

Spiniferites lenzii (Below, 1982c)

Spiniferites multibrevis (Davey and Williams, 1966a) Below, 1982c.

Spiniferites ramosus (Ehrenberg, 1837b) Mantell, 1854.

Spiniferites spp. (Mantell, 1850) Sarjeant, 1970.

Subtilisphaera spp. (Jain and Millepied, 1973) Lentin and Williams, 1976.

Tanyosphaeridium variecalamum (Davey and Williams, 1966b).

Tehamadinium coummia (Below, 1981a) Jan du Chêne et al., 1986b.

Tehamadinium mazaganense (Below, 1984) Jan du Chêne et al., 1986b.

Tenua hystrix (Eisenack, 1958a) Sarjeant, 1985a.

Xenascus ceratioides (Deflandre, 1937b) Lentin and Williams, 1973.

Xenascus spp. Cookson and Eisenack, 1969.