“Better Angels of Our Nature”: Warmth and Optimism in Presidential Leadership ()

1. Introduction

Among historians, political scientists, and philosophers, there is scant theory of the political leader who engenders warmth, confidence, optimism, and charisma among his or her followers. Perhaps form follows function. After all, leadership is hard work, and fraught with crises and risks—not only to the polity but also to one’s own career. Thus, Machiavelli advised the prince, “it is much safer to be feared than to be loved… [men] are ungrateful, fickle, simulators and deceivers, avoiders of danger, greedy for gain; and while you work for their good, they are completely yours… but when [danger] comes nearer to you they turn away” (Machiavelli, 1984 [1513]: p. 56) . Hobbes argued for powerful state leadership out of no vision for a better life, but rather the avoidance of a bad one: “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Voltaire’s Candide vigorously assaulted optimism in public affairs, a theme sustained by Nietzsche, Marx, and Sartre. Modern observers have diagnosed dark personality traits in some U.S. presidents (Freud & Bullitt, 1966; Barber, 1972; Shenk, 2005; Ghaemi, 2011; Buser & Cruz, 2017).

Yet for every example, there are counterexamples: Reagan (“Morning in America”), George H.W. Bush (“a kinder, gentler nation”), and Clinton (“Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow”). On a typical New Year’s Day, Theodore Roosevelt personally greeted thousands of visitors to the White House with a hearty handshake, toothy grin, and the word, “Dee-lighted!” Edmund Morris wrote, “He indeed delights in every aspect of his job” (Morris, 1979) . In 1933, Oliver Wendell Holmes assessed FDR as “A second-class intellect, but a first-class temperament” (Ward, 1989) . Dwight Eisenhower wrote that FDR “exuded an infectious optimism… [He was] able to convey his own exuberant confidence to the American people” (Greenstein, 1994: pp. 54-55) . Even Lincoln routinely mustered humor and expressions of optimism to motivate those around him—and in his first inaugural address, he appealed to “the better angels of our nature” to promote negotiation to restore the Union.

These examples and counter-examples beg this inquiry: are warmth and optimism attributes of presidential leadership? If so, in what ways are they manifest? Are they associated with a president’s life background or current context? And do warmth and optimism presage the esteem in which a president is later held? These are important questions, answers to which can illuminate presidential style and the dimensions by which we define leadership.

Missing in research on leadership is an assessment of warmth and optimism as a leadership style, their prevalence and dimensions, the instruments by which warmth and optimism are intentionally practiced, and the elements of context and life experience that seem to presage them. “Optimism,” says the Oxford English Dictionary, is “Disposition to hope for the best or to look on the bright side of things; general tendency to take a favourable view of circumstances or prospects” (Simpson & Weiner, 1989: p. 10, 877) . The creed of the Optimist International organization offers attributes: sunny, enthusiastic, cheerful, and happy (Optimist International, 2023) . “Warmth,” says the OED, is defined including “strength or glow of feeling, …ardor, enthusiasm; cordiality, heartiness” (Simpson & Weiner, 1989: p. 19, 918) .

This study examines self-narrative texts of post-World War II presidents, including memoirs, inaugural addresses, and State of the Union messages. It is the first to assess sentiments in presidential memoirs, and to compare attributes of personality among presidents using natural language processing. Analysis reveals that these presidents express sentiments of warmth and optimism significantly more than a mass of post-World War II literature. Yet the presidents vary considerably in these sentiments, which are significantly associated with aspects of a president’s own life experience, and with aspects of the context of the president’s time in office. The findings reveal no association of warmth and optimism with one measure of a president’s legacy, the ranking by historians. The findings here are consistent with the broader literature on personality and leadership and help to inform the ongoing study of the presidency by historians and political scientists. The analysis of presidential sentiment appears to be a fruitful avenue for future research.

This discussion proceeds as follows. Part 2 highlights prior research on optimism as an attribute of personality and on its potential relation to leadership. Part 3 reviews the research design and method for textual analysis applied here, natural language processing, as well as the sample of presidential texts to be examined. Part 4 presents the findings. And Part 5 concludes the study with a summary and questions for future research.

2. Warmth and Optimism as Attributes of Presidential Leadership

Warmth as an instrument of influence was a subject of comment from the early 20th Century. Dale Carnegie’s book, How to Win Friends and Influence People, described smiling as a “simple way to make a good first impression…The effect of a smile is powerful” (Carnegie, 1936: pp. 66-68) . In more recent research, Robert Cialdini highlighted liking as a lever of social influence: “Few of us would be surprised to learn that, as a rule, we most prefer to say yes to the requests of people we know and like. What might be startling to note, however, is that this simple rule is used in hundreds of ways by total strangers to get us to comply with their requests” (Cialdini, 1993: p. 136) .

The scholarly literature on leadership attributes is vast. Clawson (2012) estimates that some 300 leadership attributes have been identified. Stogdill (1981) surveyed over 3000 sources published from 1947 to 1980 and summarized attributes of leaders such as task orientation, persistence, originality in problem solving, social initiative, self-confidence, resilience to stress and frustration, and social intelligence (Clawson 2012: p. 81) . Seligman and Peterson (2004) concluded from laboratory studies that leadership is a cluster of personality traits that include cognitive, interpersonal, and administrative strengths (Seligman & Peterson, 2004: pp. 366-367) .

Martin Seligman advanced the relation between optimism and leadership in his research on “learned optimism.” Marshalling a large volume of studies, he argued that an explanatory style (to oneself and others) of optimism or pessimism is associated with various outcomes. For instance, the pessimist will “back talk” in self-defeating terms. He said that pessimists have an explanatory style that defeats attempts to recover from setbacks, whereas optimists’ style assists recovery. In politics, he found that the candidate with a more pessimistic style will make less effort to win, will be less well liked by voters, and inspires less hope among constituents; all of this predicts that the more pessimistic candidate will lose the election. Seligman studied hundreds of presidential campaign speeches from 1948 to 1984 and found that “the more optimistic candidate won nine of the ten elections” (Seligman, 1991: p. 189) . Moreover, the size of the electoral victory was positively associated with the degree of the candidate’s optimism. He later expanded the study to cover all presidential elections from 1900 to 1984 and found that the more optimistic candidate won in 18 of 22 elections and added, “In all elections in which an underdog pulled off an upset, he was the more optimistic candidate…with landslides won by candidates who were much more optimistic than their opponents” (Seligman, 1991: p. 252) .

Positive psychology and research on optimism are not without their critics. Barbara Ehrenreich (2009) faulted the optimism research for thin evidence, low statistical significance, and findings that could not be replicated or, if replicated, could not be affirmed. She chastised the “ideology” of positive thinking and encouraged readers to replace it with “existential hope.” She noted that the unpreparedness for disasters is founded upon optimistic bias. Weighing research on optimism, Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman (2011) warned against optimistic bias as a significant source of risky behavior (Kahneman, 2011: p. 252) .

To these criticisms of positive psychology, Seligman (2011) cited even more scholarly research, and accused Ehrenreich of “cherry-picking” the research to suit her claims. And he argued that Kahneman’s view amounts to Seligman’s own recommendations against delusional optimism.

This dispute about the validity of optimism as a leadership attribute invites a re-examination of presidential leadership. Do these modern leaders display attributes of optimism and warmth in their self-narratives, and do they differ in their degree of optimism? I study the hypothesis that presidents and their narratives will be more optimistic than others. These individuals have run an extraordinarily demanding and selective gauntlet to gain the presidency, which, consistent with Seligman’s findings, would tend to screen out pessimists. As the presidential memoirs unanimously describe, the White House is a consuming experience for its occupant and probably requires emotional reinforcement of some kind. Plausibly, optimism is an element of that reinforcement.

The texts of presidential self-narratives can tell us much about accountability, the historical context, conflict as the tool of leaders, ideologies, authenticity, and leadership in general. This study focuses on what this literature can tell us about the optimism of presidents, and thereby complements other insights about the attributes of presidential leadership.

Roderick Hart pioneered the computer-based analysis of the communication style of U.S. presidents in his 1984 study of over 400 speeches by presidents from Truman to Reagan (Hart, 1984) . Using the DICTION application software (which he developed), Hart identified stylistic consistencies of presidents versus other speakers. And he found stylistic differences among the presidents. Truman, Eisenhower, and Ford were relatively awkward and rough-hewn in speech-making—all seemed ill-at-ease. At the other extreme, Kennedy and Reagan proved to be adept rhetorical stylists. Summarizing research on presidential speeches, Hart and Daughton wrote, “Generally speaking, three features seemed linked to presidential role: 1) humanity (presidents used the most self-references, were most optimistic, and compared to business executives, were more people-centered); 2) practicality (presidents used concrete language and chose a simpler style than their counterparts); and 3) caution (presidents used less assured language than those running for office and dramatically less than the preachers studied)” (Hart & Daughton, 2005: p. 216) . In a recent analysis of presidential leadership rhetoric, Diane Heith found that Presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama displayed a “universality of voice…used the same levels of Activity, Optimism and Certainty in their national addresses” (Heith, 2015: p. 141) .

Presidential memoirs are a neglected subject of research. Scholars deem some of these texts to have been significantly staff- or ghost-written, and tend to view them as exercises in self-promotion, selective memory, and even mendacity. Nonetheless, these texts reveal what these leaders valued in their own stories, and what legacy they sought to shape. Seligman noted that what candidates say, “usually reflects the underlying personality of the speaker. Either he rewrites the speech to his level of optimism, or he picks ghostwriters who match him on this important trait” (Seligman, 1991: p. 191) . Presidential self-narratives warrant closer study as resources for the development of new leaders. What the presidents say about their own leadership—and how they say it—can be powerful examples to others. Just as important, these narratives can illuminate the attributes to seek or avoid in candidates for the presidency. Even if one denies that the words in a memoir reflect what happened, it seems reasonable to assume that those words reflect virtues that the former president wished to signal to the broader public, as the basis for a legacy. Important are the sentiments and attributes by which the president wished to be remembered.

3. Research Design and Method of Analysis

I investigate the linguistic sentiment or tone that appears in post-World War II presidential memoirs, inaugural addresses, and State of the Union addresses—these being the prominent tone-setting texts for each presidential administration. The three kinds of texts afford different vantage points at which to measure the sentiment of optimism of the respective presidents: 1) upon taking office (the inaugural addresses), 2) while in office (the State of the Union addresses), and 3) subsequent perspectives on development as a leader or on public service (the memoirs).1

3.1. Hypotheses

The alternative hypothesis of this study is that attributes of warmth and optimism characterize presidential self-narratives. I analyze the texts in four ways:

1) Presidential optimism compared to public optimism. Do U.S. presidents express themes of warmth and optimism relatively more than a broad sample of contemporary writing?

2) Variation of optimism among presidents. How unified or different are the presidents in expressing such sentiments?

3) Contingency of presidential optimism. Is the extent of optimistic sentiment associated with the person’s life experience and the context while serving in office?

4) Association of presidential optimism with historical reputation. Ultimately, is optimistic sentiment linked with a president’s legacy?

The general null hypothesis is that attributes of warmth and optimism do not characterize presidential leadership.

3.2. Method of Analysis

To explore these questions, this study of presidential self-narratives applies an algorithm used in academic and professional literature, the DICTION text-analysis program (version 7.0). In general, each of the text analysis algorithms tabulates the frequency of particular words associated by prior linguistic research with specific sentiments. DICTION provides measures of sentiment on 40 dimensions, of which 18 are consistent with the focus of this study. DICTION affords a measure of optimism, which is a concatenation of six attributes (praise, satisfaction, inspiration, blame, hardship, and denial). In addition, since optimists tend to express confidence about the future, I report a measure of certainty, which is a concatenation of six attributes (tenacity, leveling, collectives, numerical, ambivalence, self-reference, and variety). Regarding warmth, I refer to measures of rapport, cooperation, inspiration, and satisfaction. See Appendix 1 for the definitions of these attributes.

The DICTION algorithm reports the standard deviation of the count of words associated with each attribute in 500-word segments of each text from a mean of word counts in some 50,000 texts of material published since 1950. This metric is useful for testing the first and second research questions, the similarity of presidential texts to the general mass of published texts and the variation among the presidents.2 To address the third research question, I tested the association between the metrics of optimism and various measures of context and life experience, using the Pearson correlation coefficient. And regarding the fourth research question, the Pearson coefficient tests for association between the metrics of optimism and ranking of the presidents in two prominent surveys.

3.3. The Sample of Study

This study considers the memoirs and major speeches of presidents Harry Truman through Barack Obama. The memoirs of life and presidential experience range from Lyndon Johnson’s single volume memoir to Eisenhower’s three volumes and to Jimmy Carter’s corpus (to date) of 36 volumes, whose subjects range across memoir, political commentary, and religion. John F. Kennedy left no memoir; Gerald Ford gave no inaugural address. To gain the presidents’ self-reflective insights, I focused exclusively on the major addresses and those books dealing directly with the presidents’ time in office (including the White House and other elected or appointed positions) and earlier life. The texts analyzed in this study are given in Table 1. The 20 volumes of memoir aggregate to about 4.5 million

![]()

Table 1. Sample of presidential self-narratives studied.

*Reflects multiple State of the Union messages by a president in one year.

4. Findings: What the Sentiment Analysis Reveals

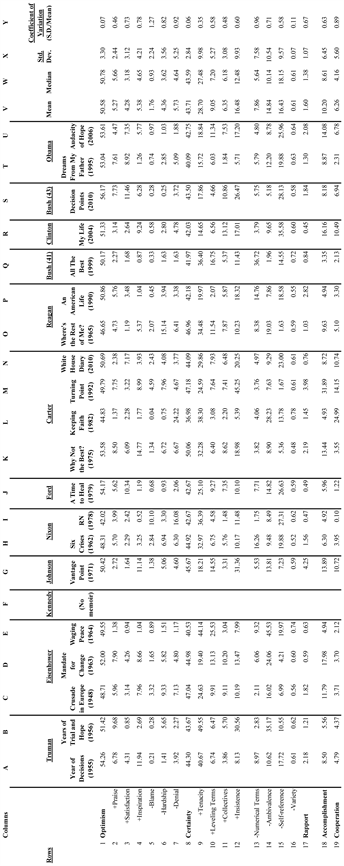

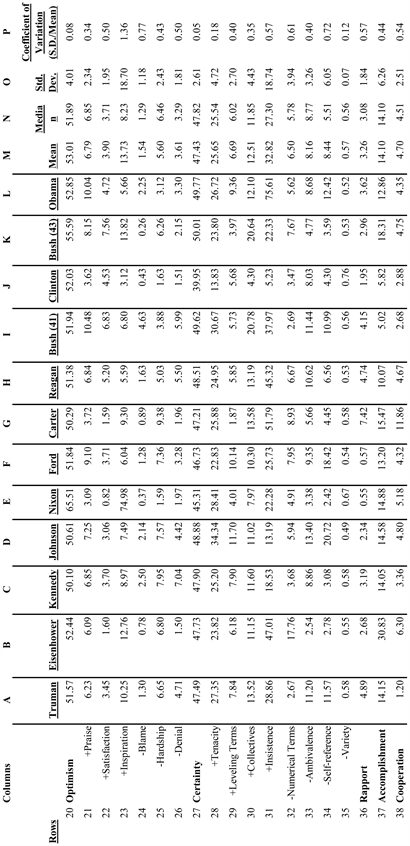

Tables 2-4 report the attributes of presidential self-narratives compared to a mass of 50,000 post-war texts. Each cell in these tables presents the standard deviation of word counts of the memoirs relative to the benchmark mass of texts for the presidents’ memoirs (Table 2), State of the Union Addresses (Table 3), and inaugural addresses (Table 4). By the convention of Student’s t-test, values greater or equal to 2.04 indicate a chance of less than five in one hundred that the result could be due to random error. These tables also present summary statistics on every measured dimension (see right-hand columns) and for every president (see Table 4, rows 58-62).

The first notable insight offered by these results is that the presidential self-narratives display high positive measures of optimism (52.19 standard deviations from the mean), certainty (46.54), accomplishment (10.21), and cooperation (5.00)—all of which are highly significant. Even rapport, though comparatively smaller in measured effect (2.42) still exceeds conventional levels of statistical significance (see Table 4, Column M, rows 58-62).

A second insight concerns the difference of perspective. Comparing the memoirs (Table 2) to State of the Union Addresses (Table 3), and then to inaugural addresses (Table 4), measures of optimism generally change—the presidents seemed to get less optimistic with the passage of time. Inspecting Table 2, column V, and Table 3 and Table 4 column M:

· Optimism declines slightly (53.68 to 53.01 and to 50.58) owing to substantial declines in the incidence of language of praise (12.44 to 5.27) and inspiration (12.2 to 5.38).

· Certainty declines materially (50.32 to 47.43 and to 43.71) because of a large decline in use of the language of insistence (27.66 to 16.48) and of a material

Table 2. Memoirs. measures of optimism in presidential self-narratives estimated as standard deviations from the mean of a distribution of 50,000 post-war documents.

Table 3. State of the union addresses. Measures of optimism in presidential self-narratives estimated as standard deviations from the mean of a distribution of 50,000 post-war documents.

Table 4. Inaugural addresses (Panel A) and summary averages (Panel B) for measures of optimism in presidential self-narratives estimated as standard deviations from the mean of a distribution of 50,000 post-war documents.

increase in the language of ambivalence (9.93 to 14.84). The use of language of tenacity declines modestly (31.52 to 28.70).

· Rapport falls by half (3.23 to 1.60).

· Perhaps offsetting the trends of optimism, certainty, and rapport over time, the use of language of cooperation rises (4.62 to 6.26).

Though the sentiments of optimism remain statistically significant across the three kinds of text, the components and intensity of this optimism decline from before, during the presidential administration, and to the memoirs.

Third, the results show the extent of variations in optimism among the presidents. The coefficient of variation (Table 2, column Y and Table 3 and Table 4 column P) indicates relative unanimity among the observations. In Table 4, rows 58 and 59 column P are very close to zero, indicating little relative variation in the summary measures of optimism and certainty in Tables 2-4—the presidents are well aligned on these two dimensions. Inspecting the components of the optimism measure, one sees relatively large variation in the degree to which presidents use language of inspiration (rows 4, 23, 42), blame (rows 5, 24, 43), hardship (rows 6, 25, 44), and denial (rows 7, 26, 45). In other words, variation in optimism arises not from accentuating the positives but rather from the degree to which they accentuate negatives.

The differences among the presidents are displayed in Table 4, panel B, rows 58-62, which give the average measures for the addresses and memoirs by individual. Across the five summary dimensions, a few presidents stand out:

· Optimism: Johnson (55.18 standard deviations from the mean) rates highest owing to a very high optimism score for his 1965 Inaugural Address. G.W. Bush (43) rates second-highest (55.10) reflecting the high measured optimism in his memoir (56.17). At the other end of the scale are Kennedy (48.96) and Reagan (50.00).

· Certainty: Kennedy (49.15) and Johnson leads the field (47.56), followed by Truman (47.19)—both presidents are notable for their sentiment of tenacity in their addresses. Hart and Childers (2004) find that verbal certainty has declined in the presidents since 1945. The lowest measures are associated with Ford (44.70) and Clinton (44.51) who are notable for the low incidence of the language of insistence in their narratives.

· Rapport: Kennedy (3.79) and Reagan (3.33) stand out for their sentiment of rapport; at the other end of the scale are Eisenhower (1.52), Nixon (1.62), and Ford (0.53). Mervin (1995) wrote, “The man in the White House must be able to speak to the American people in a language that they can understand; it is essential that they establish a rapport with their fellow citizens and this requires that they command their trust. Reagan was able to do this” (Mervin, 1995: p. 23) .

· Accomplishment: Truman (12.65) and Obama (12.85) employ this language most heavily. Eisenhower (4.24) and G.H.W. Bush (41) (4.85) use this language the least.

· Cooperation: Carter (11.47) stands apart from the field in the heavy use of this language; Ford (2.77) and Bush (41) (3.41) use it the least.

Perhaps the significant variation in measures of optimism that we observe among the post-World War II presidents is an artifact of their formative experiences in life (such as military experience, years in political life, major offices held before the presidency) or circumstances that prevailed during the particular presidential administration (such as war or economic growth/recession, or same-party political majority). The texts express one’s experience, and context could account for the sentiments in each president’s self-narrative. Therefore, I tested for possible association between measures of context or life experience and the elements of sentiment assessed by DICTION.

The measures of context and life experience considered in this analysis consisted of the following:

· Economic growth: measured as the arithmetic average of the growth rate of real gross domestic product (GDP) rate per capita during the years in which the individual occupied the White House. The estimates of growth were adopted from the Maddison Project Database (Bolt & van Zanden, 2020) .

· War footing: measured as number of persons on active duty in the U.S. military as a percentage of the total U.S. population at the end of the president’s administration. This is a broader and better measure than formally declared wars by act of Congress, since the Cold War entailed the stationing of active-duty troops without engagement of adversaries and since some other hostilities in the post-World War II era were “police actions” taken by executive order, not act of Congress.

· Offices held: measured as binary variables, whether the president had previously served in the U.S. House, Senate, state legislature, state governor, ambassador, or as vice president.

· Years in White House: measured as years served as president.

· Alignment with Congress: measured as size of the president’s own party’s voting bloc in the House and Senate, at the start and end of the president’s occupancy of the White House.

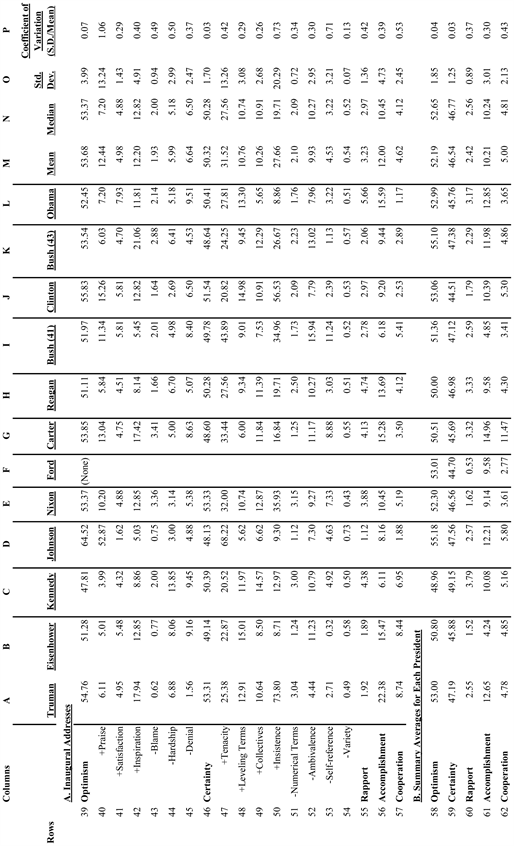

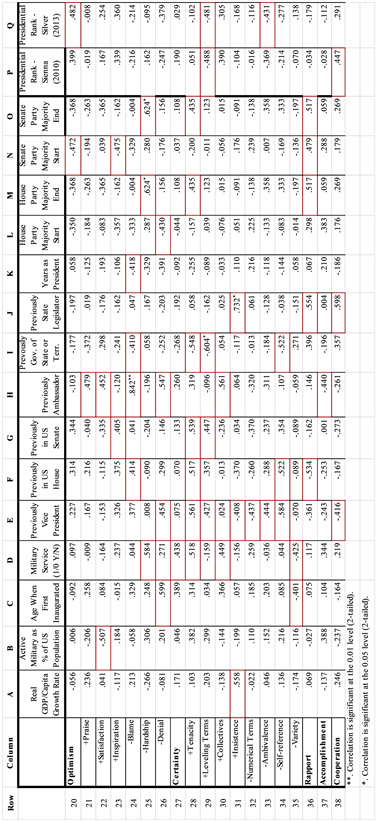

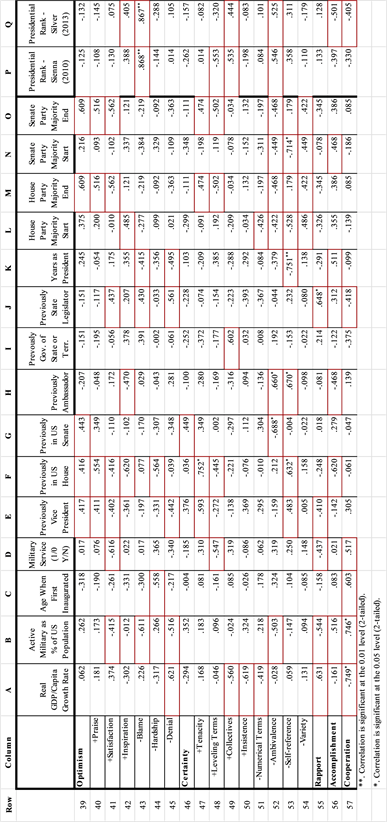

As a test of association, I report the Pearson bivariate correlation coefficient as estimated between these measures and the attributes of optimism, estimated upon the word counts in the memoirs, State of the Union Addresses, and Inaugural Addresses. Tables 5-7 present the coefficients, highlighting both statistical significance and materiality (i.e., in excess of ±0.40).

Numerous coefficients are material and/or significant—significance is estimated through conventional statistical tests; materiality is indicated in Tables 5-7 as those coefficients at 0.40 or greater. The significant coefficients are somewhat more numerous in the addresses (Table 6 and Table 7) than in the memoirs (Table 5). The noteworthy associations reside not in the meta-measures (optimism and certainty) but in their components. And the coefficients show little consistency in the size, sign, or significance of the coefficients from one table to the next—the impact of context and life experience varies over time.

Table 5. Memoirs. Pearson correlation coefficients, estimating levels of association between optimism attributes and factors of context and life experience as displayed in the self-narratives of post-world war ii presidents of the U.S.

Note: highlighted cells indicate correlation coefficients in excess of ±0.40.

Table 6. State of the Union Addresses. Pearson Correlation Coefficients, Estimating Levels of Association Between Optimism Attributes and Factors of Context and Life Experience as Displayed in the Self-Narratives of Post-World War II Presidents of the U.S.

Note: highlighted cells indicate correlation coefficients in excess of ±0.40.

Table 7. Inaugural addresses. Pearson correlation coefficients, estimating levels of association between optimism attributes and factors of context and life experience as displayed in the self-narratives of post-world war II presidents of the U.S.

Note: highlighted cells indicate correlation coefficients in excess of ± 0.40.

A close inspection of Tables 5-7 highlights attributes significantly associated with the factors of context and life experience:

· Satisfaction: negatively associated with war footing (significant in the memoirs, Table 5, row 3; material and insignificant in the addresses Table 6, row 22 and Table 7, row 41). Perhaps this reflects the impact of military activities in Korea, the Cold War, Vietnam, the Middle East, and various smaller police actions.

· Inspiration: in the memoirs is positively associated with Congressional majorities (memoirs, Table 5, row 4)—however the sign changes to negative in the addresses. Perhaps the memoirs reflect the benefits of Congressional majorities, whereas in the addresses the majorities relieved the need for presidents to give a legislative “call to arms.”

· Tenacity: in the memoirs, this is significantly associated with GDP growth, war footing, and the president’s own military service (Table 5, row 9). In the addresses, tenacity shows a material association with prior political and military service (Table 6, row 28 and Table 7, row 47).

· Insistence: in the memoirs, this is significantly associated with Congressional majorities at the end of the president’s term (Table 5, row 12). Yet such an effect disappears in the addresses.

· Numerical terms: the perfectionism implied in the use of such terms is significant and negative in the memoirs in relation to Congressional majorities at the start of the term—and significant and positive in regard to previous experience as an Ambassador (Bush (41)) (Table 5, row 13). Yet such an effect disappears in the addresses.

· Ambivalence (or caution): in the memoirs is significantly associated with war footing (Table 5, row 14) and is materially associated with several factors in the inaugural addresses (Table 7, row 52), though it is not significant or material in the State of the Union addresses.

· Self-referential language shows numerous significant coefficients in the inaugural addresses (Table 7, row 53), though the significance vanishes in the State of the Union Addresses. Perhaps this is an artifact of the aspirational nature of the Inaugural—platitudes versus policies. Inaugurations are more about intentions, while State of the Union addresses are about specific actions and outcomes.

· Cooperation is significantly associated in the memoirs with Congressional majorities at the end of the president’s term (Table 5, row 19). In the Inaugural Addresses, cooperation (Table 7, row 57) is positive and significant with war footing and negative and significant with GDP growth.

In short, Tables 5-7 affirm that context and life experience are associated with sentiments in the presidential self-narrative. The clear association between optimism and relations with Congress is consistent with a close reading of the memoirs. Every post-WWII president experienced significant episodes of tension and resistance from Congress, which were mitigated by supporters from the same party. To the extent that party-line support was sufficient to sustain the presidential program, accomplishment, rapport and collective feeling would likely be higher. Worthy of further research is the lower level of satisfaction expressed in these memoirs, as the president experienced House and Senate majorities by the end of his term in office.

Given the very large number of coefficients tested for significance in Table 3, some of the significant findings may be the result of Type II Error (accepting a false). Yet overall, it seems safe to conclude that context and life experience have an important association with the optimism expressed in presidential self-narratives: what matter in the presidents’ expression of optimism are congressional majorities, the president’s previous public service, and national context (war and economic growth). In short, optimism is contingent: one size does not fit all presidents or their situations.

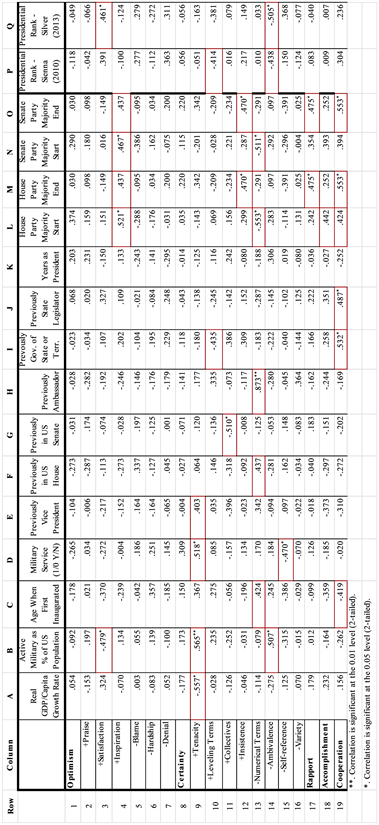

It may be tempting to infer an association between optimism and the regard in which history has held a president. Table 8 presents the rankings of the post-World War II presidents from two sources. The Siena College Research Institute Survey of 2010 polled 238 scholars. The other ranking by Nate Silver of the New York Times in January 2013, was based on a composite of previous surveys of scholars. Is there any statistical support for this inference?

Tables 5-7 (columns P and Q) presents the Pearson bivariate coefficients for correlation between the measures of optimistic sentiment and the rankings of presidents according to two prominent surveys of historians and political scientists. A

![]()

Table 8. Ranking of post-World War II presidents according to two surveys of historians and political scientists.

Note: The Siena College Research Institute Survey of 2010 polled 238 scholars. The ranking by Nate Silver of the New York Times in January 2013 was based on a composite of previous surveys of scholars.

hypothesis of higher optimism with a more esteemed legacy (i.e., a lower rank number) would imply a negative sign on correlation coefficients. The rankings and attributes of optimism show generally low and insignificant levels of association--yet, for memoirs and inaugural addresses, the correlation coefficients for optimism are negative, consistent with the hypothesis (Table 5, lines 1 and Table 7, row 39, columns P and Q). And more language of satisfaction in memoirs is associated with a better rank (see Table 5, row 14). But generally, the findings suggest little to no association between a president’s ranking and the attributes of optimism and warmth in his texts.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

This study examined self-narrative texts of post-World War II presidents, including memoirs, inaugural addresses, and State of the Union messages. It is the first to assess sentiments in presidential memoirs, and to compare attributes of personality among presidents using natural language processing.

Analysis reveals that these presidents express sentiments of warmth and optimism significantly more than a mass of post-World War II literature. Yet the presidents vary considerably in these sentiments. The variation is significantly associated with variance across the presidents’ own life experience, and with aspects of the context of the presidents’ time in office. The findings reveal no association of optimism with one measure of a president’s legacy, the ranking by historians.

This warrants a reconsideration of the role of warmth—the “happy warrior”—in leadership. Presidents reveal levels of warmth and optimism that significantly exceed the mass of modern writing. These sentiments shift modestly over time for each president, as seen in declining levels of praise, satisfaction, and inspiration, and the rising expression of ambivalence or caution—perhaps this is a natural result of aging or hard experience. And optimism varies among the post-World War II presidents, especially in their expressed blame, inspiration, hardship, and denial. The evidence suggests that variations in context and life experiences of the presidents are associated with variations in attributes of optimism. In short, optimism is a significant and material attribute of presidential self-narratives.

Yet, optimism is not associated with rankings of the individual presidents. With exceptions, the correlation of optimism with rankings is modest and insignificant. The inaugural addresses display somewhat greater association, and the memoirs somewhat less. In other words, optimism is a prominent attribute of presidents, but has little to no association with legacy: what might explain that conundrum?

One hypothesis, worthy of further study is that optimism is an instrument of leadership rather than an outcome by which the president could be remembered; it is a means, rather than an end; it is an affectation rather than a personality attribute. For instance, archival materials suggest that Eisenhower harbored anger and fears in private but presented confidence and warmth to the public.

Perhaps the incredible gauntlet by which Americans select their presidents may demand the attributes outlined in this study. Clinton Rossiter argued that affability “must be among the qualities that a man must have or cultivate if he is to be an effective modern president” (Rossiter, 1956: pp. 165-166) . According to James David Barber, “politicians continually reconstitute a sense of community, of sharing, of simple affection and mutuality as they exude the balm of political love…Nor does it make sense to think that all or even most of this geniality is phony in its motive” (Barber, 1972: p. 173) .

However, if warmth and optimism are merely affectations or instruments, then how are we to “know” the real president? What counts for authenticity in political life? Should we naturally discount presidential warmth and optimism as elements of the cunning by which Machiavelli advises the Prince to rule? Answers to such questions are worthy of deeper exploration.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks anonymous reviewers, Bill Antholis, Jim Detert, Roderick Hart, Will Hitchcock, Gary King, Melvyn Leffler, Sidney Milkis, Barbara Perry, and seminar participants at University of Virginia Miller Center of Public Affairs for helpful comments. The University of Virginia Darden School Foundation provided financial support. Andrew Meade McGee gave valued research assistance. Any errors or omissions remain the author’s.

Appendix 1. Names and Definitions of DICTION Attributes Surveyed in This Study

aThe descriptions are quoted from the Diction 7.0 Help Manual.

NOTES

1My thesis is that self-narratives of most kinds are exercises in virtue signaling. The researcher’s task is to identify the attributes with which the president sought to frame his public service. Leaders may vary in the literary form they choose, including full autobiography, memoir of particular events and episodes, and edited diary. Most of the texts studied here are memoirs, including reflections on earlier public service (Eisenhower’s memoir of service in World War II (Eisenhower, 1948) , Nixon’s memoir as Vice President (Nixon, 1962) , and Carter’s memoir as a public official in Georgia (Carter, 1975) ) and preparation to serve ( Reagan (1965) , and both volumes of Obama). Such texts convey signals about the virtues with which the individual sought to be remembered.

2DICTION describes these normalized scores this way: “the results from the analysis of the passage against the “normal range of scores” therefore providing you a “snapshot” of your results against the normative database contained in DICTION. …The means are derived from analyzing some 50,000 passages drawn from a wide variety of English-language texts from all sectors—business, politics, law, science, fiction, media, etc.” The normalized score, Δ, may be represented this way:

where X is the observed count of words represented in a dictionary associated with the attribute of optimism, Xmean is the average of the distribution of words associated with the attribute of optimism, and SD is the standard deviation of the distribution.

3This statistic measures the elapsed time between leaving the White House and publication of the first volume of memoirs about the presidential administration. For instance, the statistic does not count memoirs published before entering the presidency and the timing of publication of the second or later volumes of memoir.

4This t-value is approximately correct whether the degrees of freedom are 19 (for the memoirs) or nine for the two groups of addresses.