Evaluation of the Global Growth Effectiveness of Expansionary Fiscal Policies in Contracting Periods through Country Practices ()

1. Introduction

Expansionary fiscal policies implemented in periods when economies are shrinking, whether pro-growth or not, it is a question. However, its effectiveness at the global level is also a matter of debate. Combining theoretical ideas with practices is the ideal way to understand growth effectiveness. As a result, this study aims to start from the light of the literature perspective to the policy practices. Thus, this study shows the global growth effect while analyzing from the ideal to the application area.

The second part includes discussions in the literature about how expansionary fiscal policies should be to ensure growth efficiency. Although these approaches have different discourses on expenditures, tax policies, and effective distribution of resources, they complement each other to support growth. While pro-growth fiscal policy should be with effective allocation of resources, the importance of long-term spending and tax policies also becomes apparent. Almost all opinions have argued that expenditures and taxes during a contraction should support investments and areas where the private sector cannot intervene. However, long-term sustainability approaches emphasize that these expenditures should not lose the budget balance. Demand-side supports should also be policies that will directly affect consumption in the most obvious way.

The third section, using data from 55 developed and 55 developing countries, examined the expansionary fiscal policies implemented in 2007-2009. Graphs observed the similarities and differences in the two sets of countries. In addition, the policies examined implementations from the sample taken from these two sets of countries in detail. The view revealed in data and practice also enables us to observe the functionality of fiscal policies on global growth.

As a result, within the scope of this study, approaches to expansionary fiscal policies implemented in contracting periods were researched with their differences in the literature. Developed and developing country data sets comprised 110 countries comparatively searched in 2007-2009. In addition, fiscal policy practices consisting of examples of selected countries are analyzed to see the overall outlook on global growth. In conclusion, there is no uniformity in fiscal policies in both sets of countries due to budget constraints and preferences, and they cannot affect growth in the same direction.

2. Literature Review

There are many discussions in the literature about the growth effectiveness of fiscal policies in contracting periods. While some views argue that these policies are pro-growth, many approaches state that they will not be effective in the long run due to their inflationary effects and budget deficits ( Demirtaş, 2023 ). Expenditures and taxes are the primary tools for expansionary fiscal policies. However, discussions about the importance of effective distribution of resources before the type and quantity of policies date back to the Physiocrats in the 15th century. For them, the essential part is to determine the source of economic growth, identify the productive area, and transfer resources there. For fiscal policy to be pro-growth, taxes on productive areas must be reduced ( Yong, 1994: p. 5 ; Quesnay, 1963 ; Higgs, 2001: pp. 23-27 ). For this reason, the pro-global growth policy component can only be achieved by distributing resources to effective areas among all these countries.

It has been widely discussed in the Keynesian and Post-Keynesian literature that expenditures may be pro-growth despite budget deficits and indebtedness. In times of contraction, prioritization supports the loss in effective demand with government expenditures. The suggestion is to increase public investments, direct expenditures, unemployment, and cash aid ( Keynes, 2010: pp. 91-92, 319 ). The argument supports the idea that, especially in periods of falling private sector profitability and payment crises of consumption, public expenditures will ensure faster recovery and prevent the deepening of the contraction ( Minsky, 1995 ). When public expenditures increase, growth is supported through two channels. These are the direct effects of public procurement and the indirect increase in labor consumption resulting from income ( Lopez & Assous, 2010: p. 131 ). In addition, the collected tax revenues method should not suppress expenditures to support public investments ( Kalecki, 1955: pp. 13-19 ). However, some arguments emphasize that the inflationary effect of expenditures will be less in the Keynesian perspective, below the full employment level, and in the Post-Keynesians, below the natural growth ( Harrod et al., 2015: pp. 364, 376 ). On the other hand, the classic discussions on growth developed inclusively and emphasized the support of the entire economy, not just specific sectors. In other words, the economy as a whole will grow with the development of all sectors ( Smith, 2015: pp. 298-306, 752-762 ). From another perspective, expenditures should be transferred from the non-productive area (war expenditures and others) to the productive area. The resources transferred to the non-productive area do not support growth, as authorities withdraw them from the productive area ( Mill, 2009: pp. 96-98 ). On the other hand, it was also crucial that the expenditures should be sustainable and not limited to narrow periods. For example, the New Classics argued that transferring the expenditures made in these periods, especially to the field of investment, and balancing them with income in the following periods would support long-term growth ( Baxter & King, 1993 ). In addition, some arguments support that countries concentrate on public investment areas where the private sector could not achieve more success in growing. For this reason, neo-Keynesians suggested that areas such as education, health, communication, defense, justice, and regulation of financial markets remain as public policy ( Stiglitz & Square, 1998 ). They tried to explain the success of policies in some countries not only with the level of inflation over the years but also with structural factors. However, since the cause of every crisis or contraction period is not the same, they have gained a new perspective by examining that implementing expansionary policies will not be pro-growth in every case; on the contrary, contractionary policies may need to be implemented to ensure growth in the long term. However, the policies implemented in the exit strategy from contracting economies are generally expansionary ( Stiglitz et al., 1998: pp. 1-28, 73-82 ).

Different opinions come to the fore in tax policies, as in expenditures. For example, Keynes argues that income tax, inheritance tax, and capital profits directly affect the tendency to consume. Similarly, increases in taxation to pay debts directly affect the consumption channel. For this reason, fiscal policy is decisive in increasing effective demand and, therefore, supporting growth through taxes ( Keynes, 2010: p. 89 ). The issue of supporting growth by increasing effective demand through income tax exemptions has been approached critically. Since the exemption is generally more reflected in the upper-income segment and the expenses of this segment constitute a smaller proportion of their income, its impact on consumption remains lower. On the other hand, since the reflection of exemptions on the group income of the deprived segment is lower than the upper segment, it also reduces the contribution from this segment, where consumption is intense compared to income. For this reason, as the exemption rate increases, the reflection of the possible consumption channel contribution remains limited. The recommendation is that exemptions be made only under a specific income group. Another method suggestion is to reduce the social security payments of the same group ( Kalecki, 1946: p. 82 ). On the other hand, many perspectives emphasize the concept of a balanced budget since they emphasize that income should support tax expenditures ( Smith, 2015: pp. 767-1085 ; Ricardo, 2008: p. 165 ; Friedman, 1948: pp. 2-3 ; Baxter & King, 1993 ).

In summary, the literature has a broad perspective on the spending and tax channel to be pro-growth. Although each school operates from different starting points, they complement each other in the required policy set. The main arguments for policies to be pro-growth are the importance of transferring expenditures to productive areas, supporting investment and production, and making taxes and exemptions sustainable in the long term while increasing consumption. For this reason, global growth can only be achieved by effectively using resources in all countries.

3. Expansionary Fiscal Policies and Country Examples

Fiscal policy uses public finance tools to achieve specific economic goals. The main objectives of fiscal policy are to ensure full employment, support economic development and growth, support price stability and financial stability, ensure fairness in income distribution, and close the balance of payments deficit. In order to achieve these goals, fiscal policy can regulate public expenditures, taxes, budget, and borrowing policies, either expansionary or contractionary, in different periods. In their most general definition, expansionist fiscal policies transfer more money to the economy than is available by stimulating total demand through increasing public expenditures, reducing taxes, and increasing transfers1. Regarding public expenditures, current, investment, transfer, social, economic, and financial transfer expenditures come to mind. In the income policy, there are incomes such as fees, duties, goodwill, and parafiscal incomes. Regarding expansionary regulations in policies, the first tool used is taxes ( Öztürk, 2013: pp. 163-180 ; Pınar, 2017: pp. 26-44 ).

Due to the differentiation of public expenditures, the preferred policy combination becomes essential. Current expenditures are to provide public services. Payments made to employees are also under current expenditures. Since they include public goods and services, they are expenditures made to maintain the operation in general. However, investment expenditures and transfers come to the fore regarding expansionary policies in contracting economies. While investment expenditures include incentive and support packages, transfer expenditures increase purchasing power because they include unrequited payments. Social expenditures are transfer expenditures; they manifest as unrequited transfers to a specific segment of society with income difficulties, primarily when expansionist policies are implemented and aim to increase disposable income. On the other hand, tax policies can be implemented by changing tax rates or exemption from taxes.

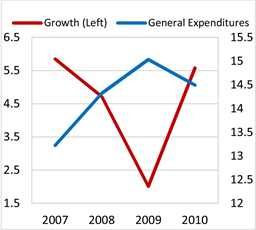

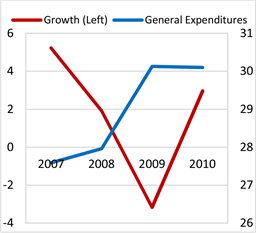

The share of general expenditures in GDP in developed and developing countries between 2007 and 2010 are in Graph 1 and Graph 2. A faster increase in spending was seen in both developed and developing countries in the 2007-2009 period. However, in the developing countries, expenditures decreased relatively in the 2009-2010. On the other hand, developed countries accomplished to keep the level of expenditures the same in the 2009-2010 period.

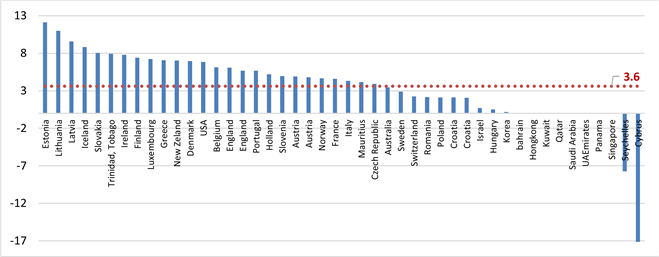

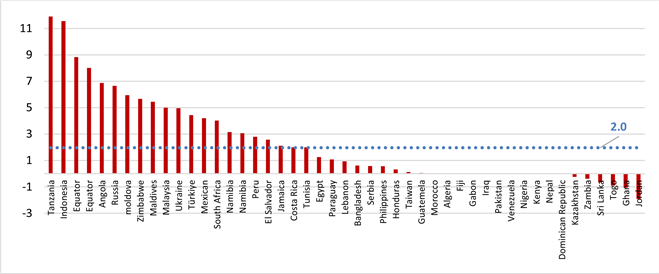

Graph 3 and Graph 4 show general spending levels on a country-by-country basis. In some countries, general spending levels remained unchanged or decreased. This situation is because of the budget constraints in the countries during the crisis period. When we look at the countries whose general expenditure

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 1. GDP share of general expenditures and growth in developing countries (%).

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 2. GDP share of general expenditures and growth in developed countries (%).

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 3. Distribution of general expenditure increase in developed countries by country (2007-2009).

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 4. Distribution of general expenditure increase in developing countries by country (2007-2009).

levels showed an upward change in the 2007-2009 period in the graphs, we see that the share of general expenditures in GDP increased by 12% in the maximum level in both groups. However, an average increase in general expenditures is only approximately 3.6% in developed and 2% in developing countries. The general outlook also shows that developing countries are more cautious about spending, and developed countries are more comfortable increasing spending due to budget constraints.

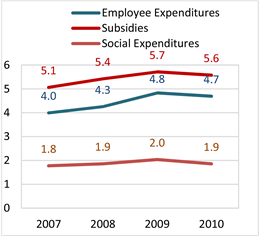

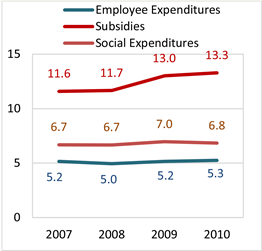

Broken down general expenditures show that the share of subsidies in GDP is higher in both country groups; it increased by approximately 1.4% in developed countries and 0.6% in developing countries in 2007-2009. Although the level of social expenditures is higher in developed countries, the share of increased expenditures in GDP in the same period (0.26% - 0.28%) is almost at the same level. On the other hand, the situation is different in employee expenses. Although there was no significant change in developed countries during this period, there was a 0.8% increase in employee expenditures to GDP ratio in developing countries (Graph 5, Graph 6).

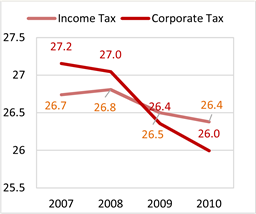

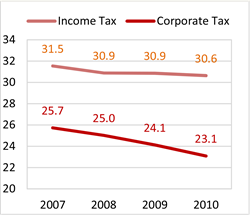

Graphs show that corporate tax rates were significantly reduced in both developed and developing countries in 2007-2009. Corporate tax rates have been reduced to 0.8% in developing countries and 1.6% in developed countries. Income tax rates were reduced by 0.2% in developing countries and 0.7% in developed countries. It can also be seen from the data that tax rates have been reduced more significantly in developed countries (Graph 7, Graph 8).

Table 1 includes the measures taken in some developed and developing countries. Table 1 shows that expenditures are both supply and demand-side. On a country basis, in some, financial expenditures are also transferred to priority sectors and areas such as infrastructure, education, defense, energy, automotive,

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 5. Distribution of general expenditures in developing countries (%GDP).

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 6. Distribution of general expenditures in developed countries (%GDP).

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 7. Tax ratios in developing countries (%GDP).

Source: World development indicators.

Graph 8. Tax ratios in developed countries (%GDP).

and agriculture. Some sectors were supported with loan guarantees, tax reductions, and supply-side direct cash aid. Some practices include cash aid for households, child support, tax deductions, and salary increases. Others have turned to increasing employment through education and have made long-term programs. Although tax incentives stand out with income and corporate tax reductions, some countries have also tried to support consumption with VAT discounts. However, the composition of countries’ financial expenditures and the allocated resource rates change as the areas are transferred. During this period, the countries’ priorities differed; while some countries allocated resources more efficiently, others expanded with a more limited budget. While some developing countries borrowed from institutions such as the World Bank and IMF in order to increase their spending, others were able to make limited spending increases due to indebtedness (Tanzania, Ukraine, Belarus, Hungary, Georgia, Hungary, Iceland, Lithuania, Pakistan2, etc.) and tried to support their fiscal policies. For this reason, when viewed from the perspective of expansionary fiscal policies, there is no uniformity in country practices focused on a specific area.

![]()

Table 1. Examples of expansionary fiscal policies in developed/developing countries.

1H.R.5140—110th Congress (2007-2008): Economic Stimulus Act of 2008|http://congress.gov/|Library of Congress; 2Actions—H.R.1—111th Congress (2009-2010): American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009|http://congress.gov/|Library of Congress; 3GAO-10-521R Health Coverage Tax Credit: Participation and Administrative Costs; https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication13504_en.pdf; 4https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/economic_governance/sgp/pdf/20_scps/2008-09/01_programme/de_2008-12-03_sp_en.pdf0; 5https://www.smh.com.au/business/france-unveils-511b-stimulus-plan-20081205-6rvv.html; 6https://www.reuters.com/article/g20-britain-brown-idINLI60838820090218. Tax hit to fund £20 billion fiscal stimulus|Financial Times (https://ft.com/). A budget for British business from Darling and Brown: Too little, far too late—World Socialist Web Site (https://wsws.org/); 7https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/economic_governance/sgp/pdf/20_scps/2008-09/01_programme/nl_2008-12-19_sp_adde%20ndum_en.pdf. Netherlands: New Stimulus Package|Library of Congress; 8https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/27/business/worldbusiness/27iht-peseta.4.18215053.html; 9https://treasury.gov.au/speech/australias-response-to-the-global-financial-crisis. Report: Government’s economic stimulus initiatives: https://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/wopapub/senate/committee/economics_ctte/completed_inquiries/2008_10/eco_stimulus_09/report/report_pdf.ashx; 10https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/156019/adbi-wp164.pdf; 11Barisitz S., Holzhacker H., Lytvyn O. vd., “Crisis Response Policies in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus Stock-Taking and Comparative Assessment”, Focus on European Economic Integratiion, Q4/10.

4. Conclusion

Within the scope of this study, the aim is to examine the contribution of expansionary fiscal policies implemented in countries to global growth during periods when economies shrank. In this context, the study first includes the discussions in the literature. Secondly, the study analyzes the data set from the developed and developing countries to see the policy direction. Finally, the study evaluates the selected country samples for the 2007-2009 practices.

It is possible to say that the literature discussions in the second part converge on the effective distribution of resources, as well as spending and tax policies that support long-term growth. Although the approaches are different, they complement each other. Even though some approaches argue that long-term policy effectiveness is impossible due to budget limits and inflationary effects, transferring resources to channels such as investment, production, and direct consumption will be adequate. The most mentioned argument is that taxes and incentives will directly support decreasing consumption in contracting periods and supply-side expenditures, especially in areas where the private sector cannot intervene.

In the third section, the appearance and implementation of policies are aggregated and examined with country examples. Expansionary fiscal policies are increases in spending, reductions in taxes, exemptions, as well as incentives and subsidies. Among the findings that emerge are those expansionary policies, which change with the increase in expenditures, are versatile and differ according to the areas preferred by countries. The policy preferences and resource transferred areas implemented by developed and developing countries in the 2008-2010 period vary. The total public expenditures under subsidies, employees, and social expenditures are evaluated here. More subsidy expenditures were made in developed countries in 2007-2009, while social expenditures remained almost the same. However, employee expenditures had increased relatively more in developing countries. When looking at tax reductions, it is clear that developed countries further reduced corporate and income tax rates during this period. However, budget constraints prevent some countries from resorting to expansionary policies, while some countries direct their expenditures by borrowing from international organizations. In addition, the direction of public expenditures, which can be both supply and demand-oriented, and the preferred sectors differ.

While some countries aim to revitalize production-oriented sectors, others allocate resources to education, infrastructure, and defense. However, sectoral preferences have also varied. Meanwhile, supply-side supports and transfers vary depending on the source countries, demand-side cash aid, support, salary increase, etc. Practices also vary from country to country. While demand-side supports remain very limited in some countries, the resources allocated are low in some countries. However, some countries prioritize long-term investments and education. Some countries allocated resources to future projects independent of the economic contraction. In other words, fiscal policies have variable policy sets shaped according to the resources and preferences of countries that emerge rather than a general practice aimed at increasing incentives and supports that will stimulate specific sectors in the supply and direct demand channels.

In summary, within the scope of this study, an attempt was made to evaluate the situation while examining expansionary fiscal policies conceptually and in terms of their application areas in countries. From the perspective of fiscal policies, although it is desirable to revitalize the economies with supply and demand side expenditures, some countries need more due to budget constraints. In contrast, some countries have prioritized only certain areas. For this reason, the resources allocated in the total sample of countries are not in the same direction to stimulate demand, and supply-side incentives and expenditures differ according to the countries’ preferences. It becomes clear that fiscal policies supporting global growth in periods of economic contraction can only be achieved by more efficient use of resources in all countries.

NOTES

1https://www.investopedia.com/financial-term-dictionary-4769738.

2https://www.twn.my/title2/ge/ge30.pdf.