Recognition of Child Maltreatment by Mothers Raising Infants Up to Four Months of Age and Types of Support Felt Necessary ()

1. Introduction

“Maltreatment,” which refers to physical, sexual, and psychological abuse and neglect in other countries, is the equivalent of child abuse in Japan [1] . It is also referred to as interactions between adults and children that may not definitely qualify as abuse, but should be avoided [2] . In Japan, the number of maltreatment consultation cases handled by Child Guidance Centers has continued to rise since collection of statistics started [3] . Among maltreatment-related deaths, infants account for over half of the cases, and in more than half of such cases, the primary perpetrators are mothers [4] . Since the 1970s, it has been believed that even lay parents engage in maltreatment [5] . According to an investigation of fatal cases of maltreatment, some perpetrators were not considered to be at high risk of committing maltreatment [6] , and 70% of mothers responded that they did not think maltreatment was someone else’s problem [7] . This goes to show that maltreatment is an act that could be committed by anyone, not only high-risk mothers, as has been previously identified, but also by low-risk mothers.

Due to the declining birth rate and families becoming increasingly nuclear, the passing on of child-rearing experiences from the grandparents’ and parents’ generations is decreasing. In addition, there has been a decrease in the number of experiences of exposure to small children in the early years of women’s lives. Therefore, it is not uncommon for a woman to experience caring for a child for the first time only after giving birth. Furthermore, the erosion of community ties may be reducing the parenting capabilities of individuals at home and in the community.

In the Japanese perinatal system, support shifts from the medical institution to the community after the first month of delivery. When the location of support provision changes, challenges arise in coordinating the transition [8] . It is more likely that some women may fall through the cracks of receiving assistance when the locus of support changes. Maternal role attainment is generally believed to be acquired around four months postpartum [9] . The risk of maltreatment is thought to increase due to feelings of anxiety and isolation that stem from the lack of familiarity with parenting [10] . Thus, assistance for maltreatment prevention requires a population approach targeting all postpartum women. However, in Japan, no interventional studies have targeted women at low risk of committing maltreatment. There have also been very few international studies. While it has been reported that preventive interventions for maltreatment are more effective when the problems of the children or parents are more severe [11] [12] , studies have also shown that interventions targeting groups at relatively low risk of engaging in child abuse can also have an impact on reducing child abuse [12] - [17] .

Therefore, the present study focused on mothers considered to be at low risk for child maltreatment, that is, mothers who had completed their one-month checkup at an obstetrical care facility, had transitioned the location of support provision from a medical institution to the community, and who were raising children up to four months of age, for whom ongoing support was difficult to obtain. The present study aimed to identify the mothers’ recognition of child maltreatment, the coping strategies they used to calm their emotions during those moments, and the types of support felt necessary. This, in turn, could help in the development of a guide for preventing maltreatment that healthcare professionals could use during one-month postpartum checkups.

2. Study Objective

The present study aimed to identify whether mothers who had undergone their one-month checkup at obstetrical care facilities and were raising infants up to four months of age recognized behavior constituting child maltreatment, the coping strategies that they used to calm their emotions during those moments, and the type of support that they felt was necessary.

3. Definition of Terminology

Maltreatment: This is a broader term for child abuse that includes physical, psychological, and sexual abuse as well as neglect by a child’s caregiver. It refers to “inappropriate involvement” and “parenting to be avoided” that includes all actions, which though may not definitely qualify as abuse nevertheless hinder the development of a child.

Population approach: This is an approach that targets a population, which may also include individuals at low risk of engaging in maltreatment, to shift the risk distribution of a whole population towards a lower overall risk and more favorable direction.

4. Study Method

4.1. Study Design

A qualitative descriptive design.

4.2. Study Participants

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “Criteria for assessing high-risk maltreatment defined in Chapter 2: Prevention of Occurrence of the Child Abuse Response Manual” [18] was used as a reference, and participants that met the criteria of being at high risk were excluded.

Twenty-one (21) first-time mothers raising infants up to four months who met the following criteria were included: 1) lived in a nuclear family; 2) were currently not residing in one’s hometown with one’s own parents; 3) ≥20 years of age; 4) had singleton childbirth with no severe maternal complications; 5) had no previous history of mental illness such as depression; and 6) were not currently working or were taking childcare leave until at least four months after birth.

4.3. Recruitment Procedure

Verbal requests were made to the heads of obstetrical or pediatric care facilities for their research cooperation. Upon receiving approval for their research cooperation, the investigator was introduced to the first-time mothers with infants up to four months of age who fit the study participant profile. Using the snowball sampling method, the research participants referred by cooperating institutions were asked to participate in the study and to assist in recruiting new research participants. The purpose of the study and methods were explained verbally when the participants were contacted by phone. An interview date and location were arranged once consent was obtained.

4.4. Duration of Data Collection

From July 2022 to March 2023.

4.5. Data Collection Method

An interview guideline was prepared based on the references previously provided on the content of child maltreatment. Semi-structured interviews were conducted using an interview guideline. The mothers raising their first child up to four months of age were asked questions relating to the following: basic attributes, details of situations that they recognized as having been child maltreatment, the coping strategies that they used to calm their emotions during those moments, and the types of support felt necessary. The mothers were told that they could speak freely. A typical question asking them whether they recognized situations of maltreatment and what coping strategies they used to calm their emotions was as follows: “Please tell me about a parenting situation in which you felt that your actions towards your child were inappropriate or should have been avoided. What coping strategies did you use during those moments to calm your emotions?” As for questions on necessary support, the investigator asked questions such as: “Please tell me what type of support you felt you needed while parenting so far.” Upon receiving consent from the participants, the conversations were recorded using a digital voice recorder. The conversations were transcribed and used as data.

Each subject was interviewed once.

4.6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the content analysis method. In analyzing the data of the present study, the content analysis method was considered ideal in its ability to objectively identify the characteristics of subjective experiences in individuals concerned that they may engage in maltreatment or may already be doing so [19] . The data were extracted in units of sentences that made sense and were related to the mother’s perception of her child, what calmed her down at that time, and what support she felt was necessary. Data were collected and coded according to similar content. The extracted codes were classified and aggregated based on homogeneity and heterogeneity, and subcategories were created. A higher level of abstraction was used for generating categories. Throughout the entire research process, to increase the validity of data analysis and interpretations, faculty advisors who are experts in the field of maternal nursing and midwifery supervised the qualitative research.

4.7. Ethical Considerations

The present study was conducted after receiving approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University (Approval No.: 2021-155). The identity of the research investigator was revealed to the study participants. The study’s intent, purposes, methods, and ethical considerations were explained both orally and in writing. The participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and that withdrawal at any time was guaranteed. The participants were also told that they could share however much they wanted to share and were allowed to withhold any information they did not feel comfortable sharing. They were assured that the information shared in the study would not be used for purposes other than the present study. Assurance was given that refusing participation in the study would not result in any disadvantages. Consent was obtained after these issues were communicated both orally and in writing.

Data of the study participants were anonymized to protect their privacy from the transcript generation stage.

5. Results

5.1. Overview of the Participants

The participants were mothers raising their first child up to four months of age, residing in the Kinki region of Japan. No major abnormalities were observed in their previous medical histories, obstetrical histories, or pregnancy/delivery/postpartum periods. No depressive tendencies were identified during the interview. The participants were financially stable and were either taking childcare leave for more than one year or unemployed. They all belonged to nuclear family households, and parenting assistance was provided by either their husbands or their own mothers. The mean age of the mothers was 31.7 ± 4.7 years (range, 27 - 46 years), and the mean age of the children was 3.3 ± 0.8 months (range, 2 - 4 months). The number of interviews was one interview per person, and the mean duration of each interview was 33.8 minutes (range, 17 - 95 minutes) (Table 1).

![]()

Table 1. Overview of the participants.

5.2. Recognition of Child Maltreatment by Mothers Raising Infants Up to Four Months of Age, the Coping Strategies That They Used to Calm Their Emotions during Those Moments, and the Types of Support Felt Necessary

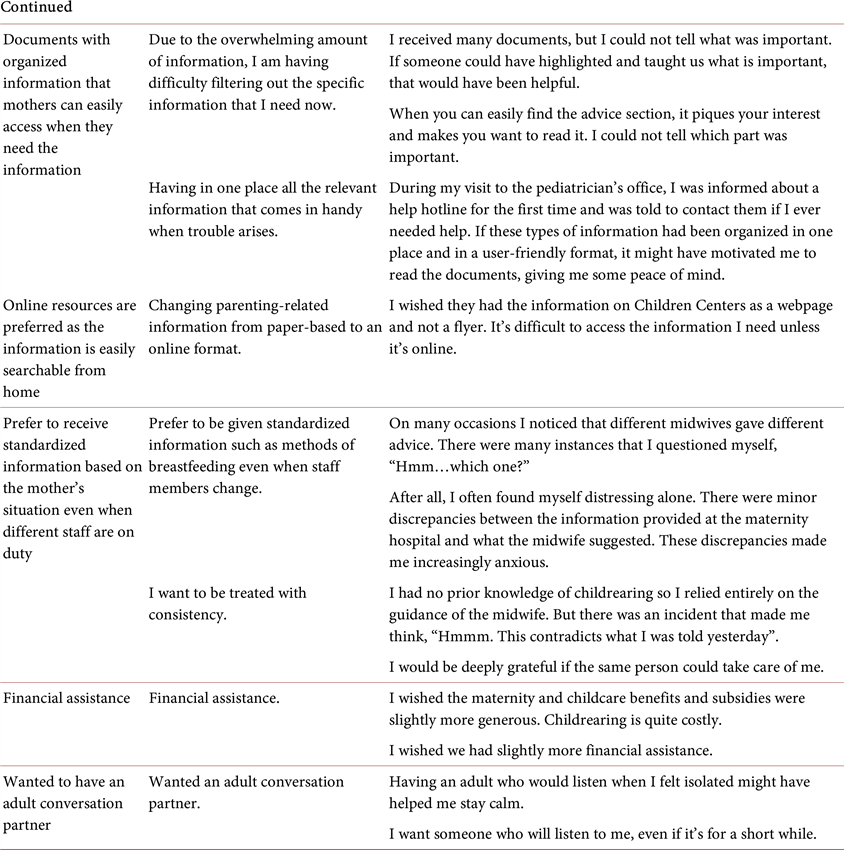

Situations that mothers caring for infants up to four months of age recognized as child maltreatment were classified into 11 categories (Table 2). The coping strategies they used to calm their emotions during those moments were classified into 10 categories (Table 3), and the types of support felt necessary were classified into 14 categories (Table 4). The meaning of the categories developed through the analysis and the constituent subcategories will be partially explained in the following section using codes and representative narratives. The following

Table 2. Situations that mothers caring for infants up to four months of age considered child maltreatment.

Table 3. Coping strategies that mothers used to calm their emotions when they recognized that they may be committing maltreatment.

symbols were used: [ ] for categories; < > for subcategories; “Italics” for the narrative; and ( ) for additional information from the author. In the main text, 21 study participants were assigned identification symbols (A to U) and are shown at the end of the narratives.

1) Situations that mothers caring for infants up to four months of age recognized as child maltreatment

a) [Becoming emotional for not understanding the child’s needs or the reason for the child’s crying and reacting confrontationally towards the child]

This comprised three subcategories: < In the beginning, I felt unsettled because I did not know why my child was crying > ; < I confronted (my child) with a questioning tone about his or her inability to stop crying > ; and < My emotions were stirred up because I did not know why my child would not stop crying > . The mothers knew they had to do something about the crying child, but they became emotional because they did not understand why their child was crying, and because of these feelings, they confronted the child with a questioning tone of voice.

Table 4. Types of support felt necessary.

b) [Acting out one’s frustrations and taking them out on the child]

This comprised two subcategories: < I lost control of my emotions over the crying and shook my child > ; and < My frustration caused me to handle my child roughly > . Triggered by the child crying, the frustrations became uncontrollable, resulting in a behavior that was deemed detrimental for the child. “Well, there was one time while I was breastfeeding at night. (My child) started wailing. So, I woke up, and I started breastfeeding. But the baby would not stop crying. Only that one time I became very frustrated with my child. It was like really feeling blood rushing to my head. At that moment, how should I put it, I shook my child a little bit, forcefully, like this. It was more like pressing my child tightly against my body.” (case: K)

c) [Failure to adapt responses to the child’s growth and development]

This comprised four subcategories: < I left my child crying without taking age-appropriate measures > ; < I ignored and left the child crying > ; < Very limited talking to my child > ; and < I prioritized my needs and had limited physical interaction with my child>. These pointed to situations where mothers did not attend to their children even when they were crying, and the interactions were primarily one-sided from the mother without adjusting responses to the child’s growth stage.

d) [Engaging in loud arguments with one’s husband in front of the children, resulting in conveying a negative message]

This comprised three subcategories: < Engaging in loud arguments with one’s husband in front of the children due to feelings of frustration towards the husband > ; < Feeling guilty about having couple’s arguments in front of the children due to parenting under tense situations > ; and < Experiencing frustration towards the husband over having to care for the child all alone > . Venting on the husband about the exhaustion and frustration of having to devote time to raising the child single-handedly resulted in arguments with the husband in the presence of the children.

e) [Becoming emotional due to breastfeeding challenges and voicing negative comments]

This comprised two subcategories: < Growing irritable due to breastfeeding challenges > ; and < Voicing negative comments to the child due to breastfeeding challenges > . The mothers voiced negative remarks because they were increasingly irritated by their breastfeeding challenges and blamed the challenges on the children.

f) [Excessive nervousness hindering one’s ability to practice parenting that is responsive to the child’s needs]

This comprised three subcategories: < Excessive nervousness limiting one’s ability to accept parenting methods other than those being taught > ; < Excessive nervousness about childcare > ; and < Excessively nervousness about the health of one’s child following the onset of jaundice > . Triggered over concerns for the child’s health, these were situations where mothers only accepted guidance provided by experts and advice written in parenting books for all aspects of a child’s living environment.

g) [Incapable of facing one’s child due to the lack of emotional control]

This comprised two subcategories: < I left home as I felt that I could not face my child in my current mental state > ; and < I became too emotional and could not interact calmly with my child > . This shows that the mothers were not always in an appropriate mental state for interaction with their children.

h) [Intense desire to be alone and putting thoughts of my child aside]

This comprised two subcategories: < Putting thoughts of my child aside and prioritizing my own desires > ; and < I would not say that I have negative feelings towards my child, but I would like some space and time alone > . This highlights how a mother feels the urge to set aside thoughts of her child, because once the child became the central focus of her life, she finds it challenging to do things that she used to be able to do. “I wish my child had not been born. I had fun when I was alone. I always have distressing thoughts like wishing I did not have a child.” (case: Q)

i) [Obsessing about taking care of the child]

This comprised three subcategories: < Trying to take care of my child all on my own > ; < Hesitation towards leaving my child in the care of others > ; and < Spending so much time with my child makes it difficult for me to let go and it can be very challenging > . In the process of parenting, when a mother tried to handle all childcare duties on her own, she became obsessed with taking care of her child and struggled to seek help from others.

j) [Growing anxious after searching for information online]

This comprised two subcategories: < Worried that my child is different from information posted online > ; and < Searching online and comparing my child to other children > . When mothers searched for parenting information online, they became concerned when encountering information suggesting that their children may be growing or developing differently. Comparing their children to others made them increasingly anxious.

k) [Incapable of interacting with my child due to physical pain]

This comprised two subcategories: < Not being able to fully pay attention and leaving my child unattended due to physical pain > ; and < Believing that one must do house chores even when exhausted leads to putting off the needs of my child until later > . This revealed how mothers felt compelled to do house chores since they were at home, even when they had not fully recovered physically.

2) Coping strategies that they used to calm their emotions when they recognized that they may be committing maltreatment

a) [Conversing with adults around them]

This comprised two subcategories: < Conversing with one’s husband or one’s own mother >; and < Conversing with adults other than family members > . This is a period when mothers spend extended periods of time alone with their children. Thus, they were regaining calmness by conversing with the adults around them.

b) [Venting frustrations and dissatisfactions to one’s husband]

This comprised two subcategories: < Lash out at the husband > ; and < Frustrated with the husband > . This indicated that the mothers were relieving their frustrations from parenting by lashing out at their husbands and not their children.

c) [Co-parenting with the husbands]

This comprised two subcategories: < My husband took childcare leave and helped me > ; and < My husband helped me care for my child even while he was working > . Feeling and realizing that they are not raising the child alone and that the husbands are co-parenting with them brought a sense of calm to the mothers’ emotions.

d) [Initiating communication by consulting with others and seeking advice]

This comprised two subcategories: < Consulting and seeking advice from those who have parenting experience > ; and < Consulting and seeking advice from experts > . This demonstrated that mothers were calming their emotions by proactively consulting others and seeking advice on their own initiative when faced with challenges and concerns over parenting.

e) [Strongly believing that one is not alone in having concerns about one’s child]

This comprised three subcategories: < Listening to parenting stories from one’s own parents and sharing current concerns with them > ; < Meeting others who are raising similarly aged children and realizing that similar concerns are shared > ; and < Receiving empathy from those who feel the same way > . Mothers calmed their emotions when they connected with others while leading isolated lives at home with just their children and realized that they were not the only ones with the same concerns.

f) [Family members are readily available to provide childcare whenever the mother is in need]

This comprised two subcategories: < Whenever I feel overwhelmed, I can swiftly leave my child in the care of family members > ; and < When I cannot look after my child, I can swiftly leave my child in the care of family members > . This shows that mothers could readily leave their children in the care of others in situations such as when they were exhausted from parenting or when they had to go to places like hospitals where they could not bring their children.

g) [Relieving their frustrations by doing something they liked]

This comprised two subcategories: < De-stressing with food > ; and < Engaging in physical activities for a change of mood > . Mothers were calming their emotions and frustrations about parenting through approaches that suited them, such as through eating or engaging in physical activity.

h) [Creating a temporary physical distance between myself and my child]

This comprised one subcategory: < Creating a temporary physical distance between myself and my child > . “Leaving my child for a while, I walk away temporarily. I take a deep breath and then return to my child.” (case: R)

i) [Experiencing a positive emotional exchange with my child and realizing that feelings are not one-sided]

This comprised one subcategory: < My child began responding to my words and actions in ways other than crying, making me realize that feelings are not one-sided > . Mothers’ emotions calmed when they sensed that their child was responding somehow.

j) [Suddenly becoming aware of one’s own actions]

This comprised one subcategory: < Suddenly becoming aware of one’s own actions > . Realizing that they had acted on their emotions and took action against their children, mothers exercised self-control through their own willpower.

3) Types of support that the mothers felt necessary

a) [Guidance from experts on the growth and development of their children, even after leaving the maternity facility]

This comprised two subcategories: < Seeking guidance from healthcare professionals on my child’s growth > ; and < Seeking guidance from experts on how to engage with my child according to its growth and development > . Mothers were seeking guidance from experts as they witnessed their children grow and encountered new reactions for the first time.

b) [Midwives being readily available to offer guidance on parenting concerns even after leaving an obstetric care facility]

This comprised three subcategories: < There is a midwife at the maternity facility who listens to my current concerns > ; < I wished there was someone available to listen to my concerns immediately when I need assistance, rather than having to wait for a scheduled appointment > ; and < I wish there was a midwife (expert) nearby during my child-raising period > . This reveals that mothers wished for midwives to be readily accessible to address their immediate concerns and anxieties. “I gave birth at a general hospital. The midwife encouraged me to ask questions if needed, but it wasn’t as if I could suddenly go and ask my question. In the end, I could not get an appointment on that day. They encourage you to ask, but the question is how should we go about asking them?” (case: K)

c) [During home visitations, I would appreciate it if an expert could listen to and empathize with my worries and concerns]

This comprised two subcategories: < I wanted more newborn visitations > ; and < Experts addressing my worries and concerns during newborn visitations > . This highlighted the fact that mothers wanted the following: i) to have experts visit their homes, where mothers care for their children every day, such that mothers can directly ask the experts whether the child-rearing environment is suitable; and ii) to be able to consult the experts in the peaceful comfort of their own home without having to go out with their child.

d) [A place where children could be cared for at the mother’s convenience]

This comprised two subcategories: < A place where children could receive care even for a short period of time if the mother needed some sleep > ; and < A place where children could receive care without worrying about the time > . This shows that mothers wanted a place where children could receive care promptly at the mother’s convenience.

e) [Provision of a gathering place for mothers with children of similar ages]

This comprised two subcategories: < Provision of a place where children of similar ages could gather > ; and < Provision of a place where mothers raising children of similar ages could interact > . This shows that the mothers wanted to interact with other mothers raising children of similar ages.

f) [Services that focus on caring for the mother’s physical and mental well-being]

This comprised two subcategories: < A place where mothers could receive care for their physical and mental well-being > ; and < Services that provide housekeeping and meal preparation support during the parenting phase > . This illustrated that mothers wanted to rest their bodies and alleviate physical and mental fatigue by reducing time spent on housekeeping chores.

g) [Interactive in-person parenting workshops]

Mothers wanted < Interactive in-person parenting workshops > . During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, opportunities to interact with others were limited due to the cancelation of in-person events. That is why mothers were looking for places to go with their children.

h) [A place where husbands could also learn parenting]

Mothers wanted < A place where husbands could also learn parenting > . This points to the fact that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, opportunities for husbands to learn directly from experts about parenting had been limited due to the cancelation of parenting workshops.

i) [Learning about postpartum mental characteristics, postpartum life, and available resources during the prenatal stage]

This comprised two subcategories: < Learning about postpartum mental instability during the prenatal stage > ; and < Learning about postpartum life during the prenatal stages > . Mothers wanted to know what would happen to their bodies both physically and mentally so that they could prepare beforehand.

j) [Documents with organized information that mothers can easily access when they need the information]

This comprised two subcategories: < Due to the overwhelming amount of information, I am having difficulty filtering out the specific information that I need now > ; and < Having in one place all the relevant information comes in handy when trouble arises > . This showed that mothers were struggling to use the information provided to them through various documents given during pregnancy. They preferred to be given information in a sequential manner that aligned with the growth process of their children.

k) [Online resources are preferred because the information is easily searchable from home]

This comprised one subcategory: < Changing parenting-related information from being paper-based to an online format > . Due to the challenges of going out with children, mothers were looking for online search tools to find consultation services and play areas.

l) [Prefer to receive standardized information based on the mother’s situation even when different staff are on duty]

This comprised two subcategories: < Prefer to be given standardized information such as methods of breastfeeding even when staff members change > ; and < I want to be treated with consistency > . This brings to light the fact that mothers were confused about receiving varying advice and interactions from different staff members.

m) [Financial assistance]

Mothers wanted < Financial assistance > . They wanted financial aid to buy items needed for the child, such as diapers and formula milk.

n) [Wanted to have an adult conversation partner]

Mothers < Wanted an adult conversation partner > . Mothers wanted someone to talk to because it was difficult for them to go out with their children, and they were increasingly spending time alone just with the child.

6. Discussion

1) < Situations that postpartum mothers up to four months after birth recognized as child maltreatment >

Maltreatment recognized by mothers raising infants up to four months of age was classified into two categories: situations where actual words were used or actions were taken against the child and situations where no actual actions were taken.

Situations where actual actions were taken were as follows: [Becoming emotional due to not understanding the child’s needs or the reason for their crying, and reacting confrontationally towards the child]; [Acting out one’s frustrations and taking them out on the child]; [Failure to adapt responses to the child’s growth and development]; [Engaging in loud arguments with one’s husband in front of the child, resulting in conveying a negative message]; and [Becoming emotional due to breastfeeding challenges and voicing negative comments].

Mothers raising infants up to four months of age perceived maltreatment as a) voicing negative words against the child, b) physical behaviors such as shaking the child, and c) having arguments with one’s husband in the presence of the child. Though these behaviors are not serious, they are considered maltreatment as defined in laws preventing child abuse. This suggested that mothers who were not considered at high risk of engaging in maltreatment were actually engaging in behaviors that could be considered maltreatment.

Triggered by events such as a child crying no matter what they did or not being able to breastfeed well, mothers lost control of their emotions when they could not have their way in managing their children’s behavior. This resulted in words and actions that were perceived to be negative to the child. Children up to four months of age can only communicate their needs through crying. Thus, unable to communicate with words, mothers must imagine their child’s needs and respond accordingly. Moreover, infants around one to two months of age go through a phase where they cry uncontrollably no matter what [20] , which is known to be unrelated to the mother’s caregiving. In addition, breastfeeding is a new experience for both the mother and child, and it is a skill that is developed gradually over time. However, with infants breastfeeding more than six times a day, regardless of time of day, and mothers becoming increasingly irritable, it is easy to imagine why the mothers might harbor negative feelings towards the child. Mothers raising infants up to four months of age often spend the entire daytime alone with their children. During these hours, even when it becomes difficult to control emotions, the mothers themselves need to find ways to calm those emotions. Therefore, it is important for mothers to learn means of self-regulating their emotions and to learn strategies for resetting their mindset when things go wrong.

As noted by < Very limited talking to my child > and < I prioritized my needs and had limited physical interaction with my child > , mothers perceived maltreatment as not actively interacting with their children due to the children’s limited responses aside from crying. Mothers who respond to the child’s needs and initiate contact through actions such as physical touching build affection between the mother and child [21] . Furthermore, it is known that active physical contact with the child intensifies feelings towards the child [22] [23] . In this age of a growing proportion of nuclear families and declining birth rates, it is not uncommon for many mothers to have their first experience of touching and caring for a child with the birth of their own child. Thus, it is possible that they may not know how to interact with children. In addition to the physical aspects of childcare, from the perspective of emotional bonding between a mother and child, it is important to encourage mothers to actively talk to their children and have physical contact with them.

Situations where actual actions were not taken but were recognized as maltreatment were as follows: [Incapable of facing one’s child due to the lack of emotional control]; [Incapable of interacting with my child due to physical pain]; [Obsessing about taking care of the child]; [Excessive nervousness hindering one’s ability to practice parenting that is responsive to the child’s needs]; [Intense desire to be alone and putting thoughts of my child aside]; and [Growing anxious after searching for information online]. Mothers working too hard to care for their children felt that they needed to interact with their children even when they were in physical and mental distress. On the other hand, there were situations where some mothers were [Obsessing about taking care of the child] and had [Excessive nervousness hindering one’s ability to practice parenting that is responsive to the child’s needs]. Furthermore, the category of [Intense desire to be alone and putting thoughts of my child aside] and the mothers’ perceiving their children negatively were recognized as maltreatment. Mothers pointed out that their ideal image of a mother and their sense of responsibility as a mother contribute to their exhaustion [24] . Because the mothers aimed for perfection in parenting, they felt guilty for not being able to interact with their children and for viewing their children negatively. This might create an environment where mothers would hesitate to seek guidance about issues of their physical and mental imbalances and the negative feelings harbored towards their children. Moreover, < Worried that my child is different from information posted online > and < Searching online and comparing my child to other children > showed that mothers are increasingly anxious about raising children. The internet does not have all the information about any individual’s child, so mothers need the skills to sift through and select pertinent information [25] . When mothers could not effectively use the information they wanted, overreliance on online information was also perceived as inappropriate childcare.

2) < Nursing implications that focus on i) how postpartum mothers up to four months after birth calmed their emotions when they suspected they might be engaging in child maltreatment and ii) types of support felt necessary >

It was suggested that mothers raising infants up to four months of age who were not considered at high risk of engaging in child maltreatment were actually engaging in behaviors that could be viewed as child maltreatment. Child maltreatment occurs in settings that are not visible from the outside, making its identification a challenge [26] . In addition, the closed nature of families makes it difficult to observe childcare from the outside [27] . Considering these factors, it is important to adopt an approach that includes providing social support to mothers who are often alone with their children and introducing a child maltreatment prevention approach for all postpartum mothers. A challenge in preventing the occurrence of child abuse is the “need to provide appropriate support when concerning signs are observed before it escalates to abuse (parenting isolation, prevention of parenting anxieties)” [18] . Therefore, to prevent mothers from becoming isolated, it might be pertinent to advise mothers to plan early where they can turn for advice.

Mothers who care for infants up to four months of age interact with their growing children daily. However, existing knowledge may not be sufficient when dealing with situations because children’s reactions change as they grow. As mentioned earlier, in this era of an increasing proportion of nuclear families and declining birth rates, many mothers will find that the child they give birth to is their first experience in child-rearing. Thus, it will be challenging for these mothers to raise their children without worries based on a self-styled parenting approach. In this situation, mothers are expected to seek support for themselves. After the one-month postpartum checkup, the setting of care provision shifts from obstetrical care facilities to the community. This timing coincides with fewer opportunities for supporters to interact with mothers. Mothers wanted to have timely access to experts who could provide guidance according to their children’s stage of growth. On the other hand, this is how they felt about information provided by current medical institutions and authorities: < Due to the overwhelming amount of information, I am having difficulty filtering out the specific information that I need now > . While there is not enough support for mothers raising infants up to four months of age, the findings of the present study highlighted the importance of: a) communicating to mothers the growth and developmental characteristics of children in short spans of time, such as at one or two months after birth; and b) providing step-by-step support for mothers, keeping in mind that the mothers are in the preparation period of raising their children in the community and in everyday life.

Through the present study, it was shown that, when some mothers felt that they might be engaging in child maltreatment, they tried to calm their feelings by [Strongly believing that one is not alone in having concerns about their children], and some mothers wished they could share parenting concerns and worries with other parents raising children of similar ages. This highlighted the importance of identifying what all mothers raising infants up to four months of age recognize as child maltreatment. The study also demonstrated the importance of learning how to control emotions and reset one’s mindset when facing challenges related to a child crying or other parenting difficulties, since these situations could act as triggers that complicate control of one’s emotions. Mothers were looking for places where they could temporarily leave their children at their own convenience, especially during moments when they faced difficulties in caring for their children due to poor physical or emotional health or when they needed to go somewhere where bringing children would not be possible. Access to postpartum care services and temporary daycares is hindered by financial constraints [28] and complicated procedures [29] . Furthermore, weak ties in the community also make it difficult for mothers to easily entrust their children to the care of others. There is a need to offer more flexible places where mothers can leave their children.

Mothers also wanted information for their partners co-parenting the children with them. [Co-parenting with the husbands] and [Venting frustrations and dissatisfactions to one’s husband] had soothing effects on mothers’ feelings. A study found that mothers experienced less parenting burden and tended to have a higher degree of happiness when they perceived that the fathers actively participated in parenting [30] . As birth rates decline and families become more nuclear, child-rearing will increasingly be carried out by the husband-and-wife team. This means that partners will assume an even more crucial role in parenting in the future. Thus, instead of providing parenting information to mothers only, it is important to offer support that allows both mothers and their partners to access and benefit from the same information.

According to the results of this study, the maltreatment perceived by mothers up to four months postpartum fell into two categories: situations in which the behavior towards the child was not at a serious level requiring some immediate intervention, but which nevertheless constituted inappropriate parenting, and situations in which the behavior was not actually committed. Even acts that do not actually constitute maltreatment were recognized by mothers as maltreatment. During parenting, every mother may experience negative feelings towards her child and may face moments when she feels incapable of engaging with her child. Simultaneously, this study identified what was holding them back in such moments from engaging in behavior that would have led to severe child maltreatment. These new findings have yet to be reported in previous studies. Based on the results, a maltreatment prevention support guide and pamphlet will be developed, and information will be provided to all mothers who have given birth to a child at medical facilities.

3) Limitations of the study and future tasks

Since the data collection period overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, behavioral restrictions and other limitations may have affected the content of the narratives. As future tasks, there is a need to develop a maltreatment prevention support guide that healthcare professionals will implement at the one-month postpartum checkup, conduct an intervention study using this guide, and verify its effectiveness in preventing maltreatment.

7. Conclusions

1) Actions considered maltreatment were observed in mothers raising infants up to four months of age.

2) Maltreatment recognized by postpartum mothers up to four months after birth was classified into two categories: situations involving actions taken towards the child and situations where no actual actions were taken.

3) Even acts that do not constitute maltreatment were recognized as maltreatment by mothers raising infants up to four months of age.

4) The importance of socially supporting mothers who are often alone with their children and providing preventive approaches for all postpartum mothers were suggested as support needed to prevent maltreatment by mothers raising infants up to four months of age.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their deepest appreciation to all the mothers and the hospital staff for their cooperation throughout this study. The present study is part of a doctoral dissertation intended to be submitted to the Graduate School of Nursing at Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University.