Dynamics in International Contract Business Negotiations: A Comparison of Brazil, Russia, Indian and China (BRIC) ()

1. Introduction

Negotiators attempt to negotiate for an optimal result minimizing conflicts and maximizing gains in a win-win negotiation scenario (Fisher & Brown, 1989; Fisher et al., 1991) . Gulbro and Herbig (1998) point out that as negotiators from different countries think and behave differently, the potential for disagreement and misunderstanding increase. Different values result in a diversity of approaches and behaviors that impact on the expected outcomes reflected in the international agreement. However, differences among negotiators from different countries may be expected and even predicted in an international business agreement. There are several issues that can cause the failure of negotiating an international agreement. To achieve consensus in an international business negotiation, negotiators have to understand traditions, ideologies, legal systems, morals and religious customs, among other factors (Liu & Liu, 2006; Baicu, 2014; Tu, 2014) . Under the globalization context, the strategies, styles, and agreements employed in international business negotiations became increasingly important (Salacuse, 2005a; Brett et al., 2017) . Thus, one of the most important issues for negotiators to achieve successful in an international agreement negotiation is to prior settle a negotiation strategy, for better understanding of international negotiations challenges.

Over the preview decades, most of the world’s economic growth has occurred in four large developing countries Brazil, India, Russia and China, coined by Jim O’Neil (2001) by the acronym “the BRICs” or the “BRIC countries”. The concept of BRIC countries is relatively new. Later on in the year 2003, Wilson and Purushothaman (2003) predicted a set of factors that would create conditions for the economic growth of the BRIC countries. BRIC countries emerged from radically different legal, economic, cultural, social and political backgrounds (Costa, 2013) . Indeed, the “fact that the concept of BRICS was created by an investment bank, while that of the Third World was formed by a demographer (Alfred Sauvy) reveals how much economic globalization has come to shape geopolitical representations” (Laidi, 2011) . In the recent past, a large number of untapped opportunities for business among BRIC countries have arisen and it became more important to take into consideration the risks involved in international negotiations among and with these countries.

Many books, articles and empirical studies have already been published concerning negotiations with different cultures (Ferraro, 1990; Salacuse, 1991, 1998, 2005b; Buttery & Leung, 1998; Thompson, 2001; Gesteland, 2002; Lewis, 2006; Costa, 2006) . Generally speaking, cultural differences, language barriers, differences in negotiation styles and lack of trust may lead to a negotiation failure. For instance, while Hofstede’s leading work on the theory of cultural dimensions help to explain cultural differences behavior (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005) based on major variables of cross-cultural differences such as power, uncertainty/avoidance, characteristics of individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity; Salacuse (1991) explores the current and characteristic elements in international negotiations. While international negotiation is a field of research with several studies, very few papers have been published internationally comparing how BRIC countries negotiate international agreements and the related implications for companies operating in and within these countries.

This paper intends to conduct empirical research in a specific business negotiation setting: negotiations of international agreements handle by BRIC countries negotiators. As misunderstandings occur during a domestic agreement negotiation within the same culture, one can affirm that the same happens when BRIC negotiators are negotiating an international business agreement. What kind of misunderstandings can prevent successful cross-cultural negotiations among BRIC negotiators? How are BRIC negotiators able to overcome the challenges of the international environment while negotiating an international agreement? Is it possible to settle a common path among BRIC negotiators based on an international business agreement negotiation? The results of this study may explain the way of doing business in and with BRIC countries, through a comparative analysis of selected usual aspects of the negotiation process of an international agreement. This study might help companies and international business negotiators in understanding BRIC’s negotiation environment and in formulating entry strategies in these emerging and challenging markets.

2. Literature Review

Negotiation is a dynamic process, involving a variety of factors that influence the negotiation outcomes (Raiffa, 1985) . Jolibert and Tixier (2002) consider that a negotiation process implies the existence of a conflict of interest among parties, without rules or pre-established fixed procedures, with the purpose of reaching an agreement. Mastenbroek (1989) describes a negotiation as a process where negotiators are in the presence of different interests, in most cases contradictory ones; however, as parties involved are some-how interdependent there is a clear advantage for all in reaching an agreement. As per Lax and Sebenius (1992) four elements characterize a negotiation process: the interdependence of the parties, the notion of conflict, the opportunistic interaction (in the current language of game theory) and the possibility of an agreement. In sum, Azieu defines negotiation as a set of contacts and maneuvers aiming to take two or more opponents sides to establish a common set-in order to reach an agreement. Negotiation strategy requires consideration of other’s party alternatives and interest in particular to create value but also to claim value during a negotiation process (Neale & Bazerman, 1983; Lee et al., 2013; Brett et al., 2017) .

A general negotiation strategy can help parties to achieve their objectives and build positive relationships. A negotiation strategy should involve the following aspects:

1) Preparation for the negotiation: Before entering into a negotiation, it’s important to prepare thoroughly by getting information about the other party’s position, as well as their interests, and values. Also, it is important to determine its own objectives and identify strengths and weaknesses, Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement, BATNA (Fisher et al., 1991) ;

2) Establishing goals: It’s crucial to set clear goals for the negotiation, in order to ensure that parties are working towards a desirable outcome;

3) Building relationships: Creating a constructive relationship with the other party can help create a cooperative and collaborative environment for negotiation (Fisher et al., 1991) . It means understanding the other party’s desires and trying to find a common ground;

4) Communication: Developing and effective communication is critical in a negotiation. Also, it is very important to listen to the other side and to learn to ask questions and seek to clarify issues that are not clear;

5) Making concessions: Negotiation may involve making concessions, as long as all the issues have been fully explored (increasing the pie of the negotiation and avoiding a fixed pie). It is necessary to understand what are the concessions that you are willing to make and what concessions are non-acceptable and in this case the choice of the BATNA is the best to do;

6) Using rational criteria: Using rational criteria, such as market value or industry standards, can help to solve disputes at the negotiation table;

7) Closing the agreement: Once an agreement has been reached and both parties agreed to the its terms of the agreement, it is important to draft a written agreement.

The scenario of domestic negotiations differs from the international one (Adler & Graham, 1989; Hendon et al., 1999) . In fact, there are some key differences between international and domestic negotiations. Domestic negotiations involve negotiators from the same culture and same country. International negotiations often involve negotiators from different cultures and different countries, which can impact communication and negotiation strategies (Brett et al., 2017) . International negotiations, contrary to domestic ones, involve negotiators who speak different languages, which can compromise communication. Domestic negotiations usually involve negotiators who speak the same language (Adler & Graham, 1989) . Domestic negotiations involve negotiating within one single legal and regulatory system. On the other hand, international negotiations involve dealing with different legal and regulatory systems, which may impact the negotiation process (Salacuse, 2005a) .

In sum, an international business negotiation can be broadly described as the interaction of two or more individuals, originating from different countries, in order to settle a business matter through the execution or not of an agreement, in written or oral form. Negotiating international agreements are typically more complex and complicated due to the involvement of multiple parties, cross-border issues, different cultural and legal systems than negotiating domestic contracts involving negotiators from the same country and legal, political, cultural and economic background (Ertel, 1999) . Actually, the international context favors the emergence of political, economic, cultural or legal conflicts and misunderstandings. International negotiations require an understanding of countries differences of the parties involved in this process in order to achieve a positive result or success in a negotiation. As per Salacuse (1991) , international negotiations have some specific characteristics. These characteristics can be used as basis to differentiate international and domestic negotiations as follows: international environment, culture, ideology, diversity of legal systems and instability.

International negotiation is a field of considerable interest in this age of globalization. As new range of international opportunities has been created in this context, the number of international agreements has increased accordingly. In fact, international business transactions, such as strategic alliances, joint ventures, financial services contracts, cross-border trading, licensing of intellectual property rights, franchising and distribution agreements became commonplace in today’s world (Nisbett, 2003; Kumar & Worm, 2011) . Despite that, international business transactions are often quite complex. The complexity aspect is mainly related to the number of variables faced by negotiators in their interactions in the international scenario (Salacuse, 1991; Brett et al., 1998; Brett, 2001; Lee et al., 2013) . In sum, international negotiation practices differ from one country to another. Based on this assumption, a special approach may be required for better comprehend the unique international environment faced by BRIC negotiators when negotiating an international agreement (Schecter, 1998; Paik & Tung, 1999; Zhao, 2000; Fraser & Zarkada-Fraser, 2002; Nisbett, 2003; Costa, 2005; Ma et al., 2013; Tu, 2014) .

3. Assumptions

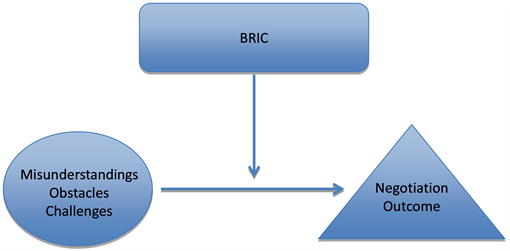

In this research study the following assumptions were tested as shown in Diagram 1: Assumptions:

Diagram 1. Assumptions.

A.1. The kind of misunderstandings that prevent successful cross-cultural negotiations among BRIC negotiators.

A.2. The kind of challenges and obstacles that BRIC negotiators have to surmount while negotiating an international agreement.

4. Methodology

Quantitative data for this study was collected by E-mail survey. Data was collected using an online survey, and a hyperlink to the survey website was provided on each e-mail invitation. Email and online survey were both in English language. No version in Portuguese, Russian, Hindi or Chinese Mandarin was provided. As the survey was related to an international agreement negotiation, respondents were expected to understand and to be able to negotiate in English. The surveys were sent to executives from BRIC countries nationalities, regardless of their current work location. One thousand questionnaires were E-mailed, representing firms listed on stock exchange market in each of the BRIC’s countries (Appendix A—Questionnaire). A cover letter with university letterhead was used to increase legitimacy. E-mail addresses of these individuals were obtained from international directories, from embassies and consulates, and from social media, in particular LinkedIn and Facebook.

All surveys’ respondents were taken randomly from several industries, such as: advertising and marketing, business support and logistics, construction, education, entertainment and leisure, finance and financial services, government, healthcare and pharmaceutical, insurance, legal services, manufacturing, non-profit, retail and consumer, telecommunications, technology, internet and electronic, utilities, among others. To avoid sampling errors, data was collected from all different sectors of the stock markets in the BRIC countries. An intensive follow-up of non-respondents was undertaken after 30 days, in particular for Chinese nationals. Generally speaking, Chinese individuals are cautions to answer surveys prepared by foreigners and related to business information considered sensitive, such as strategy, marketing, finance and contracts negotiations. Fear of the competition or governmental aspects might be some of the reasons. Data collection lasted three months. The response rate of 20 percent was low but deemed acceptable for this study (Visser et al., 1996) , as the same number of respondents from each BRIC country (50 questionnaires for each country) has been achieved, otherwise this research would have a response bias (Eisenhardt, 1989; Bryman, 2008; Yin, 2009; Burns, 2010) .

The recipients were asked to answer several questions based on their perception of a recent past negotiation experience related to an international agreement (see Appendix A). The questionnaire has eight-pages, and it is divided into two sections. The first section of the questionnaire consists of thirteen items related to organizational characteristics and recipient demographics (gender, age, nationality, level of education, language, religion, job position, work location and sector). The second section of the questionnaire takes into consideration the perceived process factors associated with a previous negotiation of an international agreement. It contains twenty-one items as follows: place where negotiations have occurred, formal or informal aspect of the negotiation, kind of agreement that has been negotiated, number of negotiators involved, respondents’ perceptions of the most relevant skills for international negotiators, preparation process for the negotiation, the actual negotiation process and outcomes of the negotiation, including the celebration or not of the international agreement.

In order to confirm the quantitative data collected by the survey, qualitative data was undertaken in each of the BRIC countries. Five personal interviews on each BRIC country were conducted. Respondents have been selected per industries sectors based on the largest number of respondents received on the survey, as follows: finance and financial services; telecommunications, technology, Internet and electronics; legal services; education and business support and logistics. One interview per industry sector from a national of each BRIC country was made, in a total number of twenty interviews with five respondents per country and industry sector.

5. Results

The results collected by this survey are divided into two sections: negotiators’ profiles and outcomes of the negotiation.

5.1. Negotiators’ Profiles

The first section of the questionnaire is related to organizational characteristics and respondents’ demographics. Overall, the majority of the respondents are male (Mazei et al., 2022) , representing seventy-eight percent of the total (Figure 1).

Ninety percent of the respondents have a graduate level of education, mainly in business, law, engineering and economics (Figure 2).

Over fifty-four percent of respondents have a senior or medium management position and thirty-six percent of respondents are top executives of private companies or owners of private firms (Figure 3).

The average age of respondents ranges between thirty and forty-nine years old (Figure 4).

English is the most spoken language of international negotiations, representing over eight seven percent ( Figure 5 ).

In sum, Figures 1-5 present the profile of BRIC countries negotiators respondents in this study.

5.2. Negotiation Outcomes

The second section of the questionnaire consists of the perceived negotiation process factors associated with a previous negotiation of an international agreement. Respondents were asked to identify a recent past negotiation of an international agreement in order to reply to the survey. Joint ventures, cross-border trading and commercial agents, financial services and services in general and distribution agreements were the most cited examples by respondents (Figure 6).

Most of recipients referred to a recent international agreement with counterparties from Europe and the US. Asia (excluding China), Brazil and China were the other counterparty’s nationalities involved, as shown in Figure 7.

![]()

Figure 5. Foreign language used on international negotiations.

![]()

Figure 7. Nationality of the other party on the negotiation.

The negotiation of an agreement, both at the domestic or international level, has three different stages: preparation for the negotiation, actual negotiation, and post negotiation phase. An effective preparation for an international negotiation is closely connected with the success of the whole negotiation process. When parties are negotiating an international agreement, the geographical and physical distance may compromise the results of the negotiation. Indeed, parties are more familiar with their own country’s environment and often ignore the peculiarities of their counterparty’s environment. Lack of preparation in an international business negotiation brings difficulties for the next stages: the actual negotiation and the post negotiation. In fact, this first step is decisive for the success of any international negotiation. As per the results of the survey, over fifty percent of negotiators from BRIC countries spent around two weeks before the first meeting preparing for the negotiation of an international agreement. More than twenty-five percent of respondents spent one day only, and two percent did not prepare at all in advance (Figure 8).

Two weeks’ preparation may not be enough if negotiators do not have previous experience with the counterparty’s environment, in particular if considered that majority of respondents were negotiating an international joint-venture agreement, a quite complex agreement.

5.2.1. Preparation for the Negotiation

Regarding the hour/length for preparing to an international negotiation, overall thirty-five percent of respondents spent more than ten hours; twenty-seven percent spent more than five hours; eighteen percent took more than two hours and three percent less than one hour (Figure 9).

Even if the overall length of preparation of the majority of respondents is more than ten hours, it may be deemed short when considered that the majority of respondents was preparing for a complex international contract negotiation such as a joint venture agreement. The classic win-win negotiation approach (“creating value”) based on Fisher’s assumption that a good negotiator must “put yourself in the other side shoes” (Fisher et al., 1991) is not considered relevant by recipients of the survey and from their perspective this assumption has no impact on the outcomes of the negotiation (Figure 10). In sum, BRIC negotiators should improve their preparation process in order to obtain better negotiation process and results.

5.2.2. Actual Negotiation

In general, the second stage of the negotiation process, the actual negotiation, involves face-to-face interactions, virtual interactions, methods of persuasion and concessions and the use of negotiation tactics in order to increase the “negotiation pie” towards a win-win negotiation (Fisher et al., 1991) . A formal negotiation process is important for most BRIC negotiators. The survey shows that eight one percent of the negotiations were formal or extremely formal in BRIC countries. In contrast, informal negotiations represent merely seventeen percent of the results, as shown in Figure 11.

BRIC’s negotiators performed international negotiations at least with another negotiator (seventy-nine percent). A sole negotiator handled very few negotiations (Figure 12).

![]()

Figure 8. Length of the preparation for the negotiation: day, month, year. * Others: 1 respondent: no preparation specifically; ** 3 respondents skipped this question.

![]()

Figure 9. Length of the preparation for the negotiation: hours. * 1 respondent skipped this question.

![]()

Figure 10. “Put yourself in the other side shoes”. * 2 respondents skipped this question.

![]()

Figure 11. Formal and informal negotiations. * 2 respondents skipped this question.

Team negotiations may provide a better environment for the exchange of information and value creation in a negotiation process than solo negotiators. This survey shows that BRIC negotiators are much more group oriented which enlarges chances of increasing the negotiation pie and value creation. Building trust and developing a relationship with the other party is important for BRIC nationals, and failure to establish trust can make difficult to reach an agreement. Face-to-face negotiations are commonplace among BRIC negotiators.

Most of the respondents handled the negotiation in their respective home countries. Few have used Internet, conference calls and similar means to negotiate an international agreement (sixteen percent). A third neutral country was barely used, representing only three percent of the survey (Figure 13).

The most relevant tools for a negotiator from BRIC countries are language skills closely followed by listening to the other party (Figure 14).

To improve the counterparty understanding of certain aspects, most of the recipients endorsed the use of examples, as well repeating in other words what has been said during the negotiation. Much of the communication breakdown in international negotiations can be attributed to language understanding.

BRIC negotiators understand how important communication is when negotiating an international agreement and make efforts to tackle the challenges of negotiating in a foreign language (Figure 15).

These behaviors are consistent with the international style of “win-win” negotiations and creating value strategy.

BRIC negotiators frequently use bargaining tactics (“win-lose” negotiations). Sixty-four percent of recipients fell extremely or quite comfortable bargaining and negotiating prices, as shown in Figure 16 and Figure 17.

![]()

Figure 13. Negotiation place. * 1 respondent skipped this question.

![]()

Figure 14. Important skills to master’s in international negotiations.

![]()

Figure 15. Improving communication skills. * 2 respondents skipped this question.

![]()

Figure 16. Negotiating prices. * 2 respondents skipped this question.

![]()

Figure 17. Bargaining tactics. * 1 respondent skipped this question.

Bargaining tactics are more consistent with the standard of win-lose negotiations (“claiming value”). These tactics aim to promote the largest slice of the negotiation pie for one side, while the other side remains with the smallest possible slice (Saner, 2000; Kern et al., 2020) . The role of relationship is recognized by eight seven percent of recipients in the process of influencing or forcing an international negotiation, as well as making concessions—in most cases mutual concessions but not necessarily—in order to reach an agreement. These behaviors are coherent with the international style of “win-lose” negotiations.

However, the use of rational criteria to convince the counterparty is endorsed by ninety-eight percent of respondents, being a tactic consistent with the “win-win” negotiation style (Figure 18).

The result shows that seventy-four percent of recipients concluded a formal and detailed written agreement, while twenty-two percent reached an informal agreement. A minority of three percent of BRIC negotiators did not reach an agreement at all (Figure 19). As a formal negotiation process is important for BRIC negotiators, it makes sense that the outcome of the negotiation is in fact a formal and detailed legal agreement.

![]()

Figure 18. Tactics to persuade the other party. * 2 respondents skipped this question.

5.2.3. Post Negotiation

The post negotiation phase tackles the evaluation of the agreement and by consequence of the negotiation process performed during the two previous stages. Besides focusing on the conclusion and execution of the agreement, other intangible aspects are explored in this phase, such as the overall level of satisfaction related to the negotiation process. Following Fisher’s seminal work Getting to Yes (1991), reaching an agreement does not mean success in a negotiation process. Said that, ninety-six percent of respondents reached an agreement. From this total, thirty-four percent of BRIC negotiators were very satisfied; a similar percentage was moderately satisfied, and twenty-five percent of negotiators were satisfied with the agreement. A minority of five percent claimed not completely satisfied and a single respondent declared as not satisfied at all (Figure 20).

Negotiators may have achieved the conclusion of the agreement but failed to get success in the negotiation process and probably in the agreement itself.

![]()

Figure 19. Outcome of the negotiation. * 9 respondents skipped this question.

![]()

Figure 20. Satisfaction with the outcome of the negotiation.

6. Conclusion

This study compares aspects related to international contracts negotiations handled by negotiators from BRIC countries nationals. Based on past experiences of international negotiations, this study explores the outcomes and relevant negotiation process issues. The results of this study show that negotiation of international agreements by BRIC countries is a very complex process. Negotiating international agreements by BRIC countries can be challenging, and there are several issues that can cause negotiations to breakdown. Negotiators from BRIC countries need to understand these issues and try to avoid them in order to make a successful deal.

What can be learned from this study? First, BRIC negotiators may improve the preparation process in order to overcome misunderstandings and to improve outcomes of negotiating international agreements. Preparation is mandatory for success on negotiations. Negotiators have to be prepared since the beginning of the negotiation process, by collecting information, refining objectives, and fixing limits. By using the data collected in this study related to the lack of an appropriate preparation in future negotiations, BRIC countries negotiators may overcome difficulties, challenges and obstacles appointed by the survey and commonly faced in the negotiation of international agreements.

Misunderstanding and miscommunication may contribute to failure in negotiating an international agreement. Language barriers are also a significant obstacle in international negotiations. In fact, negotiators who are not fluent in the language of the other party may have difficulty understanding key concepts or expressing their own ideas and proposals. This means, BRIC negotiators have to work harder in communication skills, in clarifying aspects related to negotiations in a foreign language and in understanding the different international environments.

Cultural differences can pose a significant challenge in international negotiations by BRIC countries, as negotiators from very different cultures may have not the same communication styles, values, and beliefs. Culture may have a significant influence on BRIC negotiation, as cultural norms and values impact how negotiators handle the negotiation process. Cultural differences may impact negotiation strategies, such as how negotiators approach relationship, sharing information, and bargaining techniques. When negotiators understand the cultural differences, they can find mutually beneficial solutions. Otherwise, these differences can lead to misunderstandings and misinterpretations that can interfere in the negotiation process. Differences in culture can lead to different negotiation styles that may lead to failed negotiations. Negotiators from some cultures from BRIC countries may prefer to engage in a collaborative negotiation style, while other negotiators from other BRIC cultures may prefer a more competitive negotiation style. This can lead to a breakdown and a failure in negotiations.

BRIC countries and their negotiators must realize that the negotiation of an international agreement may be the beginning of a long-term process and the frequently use of bargaining tactics might compromise the creation of a win-win negotiation process. Bargaining tactics are more consistent with win-lose negotiations and should not be used in international agreements, in general long-term and creating-value relationships. Recurrent difficulties experience by BRIC nationals negotiating international agreements may limit the opportunities of the globalization era. BRIC negotiators must devote more time and efforts to improve their knowledge on “putting yourself in other side shoes”. This implies that negotiators should devote more time creating collaborative opportunities and increasing the “negotiation pie”. In summary, failure to address the critical issues mentioned above can lead to the failure of negotiations of BRIC countries.

This study is based on perceptions of previous international negotiations of BRIC nationals. Respondents may have emphasized their perceptions instead of their experiences in answering the questionnaire. This can limit the results of this research. In order to obtain a large number of respondents, the questionnaire has been limited to explore certain selected aspects of the negotiation process of an international agreement. A number of other issues related to negotiations of international agreements by BRIC nationals have been identified, in particular during the personal interviews. Nevertheless, this paper has not an attempt to provide an exhaustive analysis. There are several issues that have not being addressed in this paper that clearly deserve close examination. The results of this study encourage future research on a better understanding of each BRIC country and to explore the differences and similarities encountered among them. Gender aspects involving negotiation of international agreement by BRIC countries nationals may be further examined.