1. Introduction

The past few years have been characterized by a significant rise in terrorist activities worldwide. Although many cases involve problems experienced at the national level, recent occurrences have been linked to international geopolitical differences. Terrorism causes significant economic disruption due to the loss of human life and injuries sustained (Clark et al., 2020) . The loss of lives, the disability caused by accidents, and the devastation of private and public property are all examples of the direct economic costs of terrorism (Clark et al., 2020) . Beyond the immediate effect, terrorism causes economic disturbances, which do not manifest for days, weeks, or months after the terrorist attack. The economic impact of terrorism on growth, investment, consumption, and tourism seriously threatens a country’s economic development and growth, depending on the scale and frequency of terrorist incidents (Clark et al., 2020) . Terrorism’s wider consequences depend on the economy’s ability to reallocate and distribute capital from the affected sectors smoothly.

Background

Terrorism changes economic behavior by shifting expenditure and consumption habits, diverting public and private capital from productive activities, and implementing defensive steps, weakening a country’s financial capabilities. Consequently, understanding the magnitude of the aftermath, assessing the economic impacts of domestic terrorism, and devising effective techniques to circumvent or prevent future invasions became increasingly important following the direct result of the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001. As global societies continue to experience a growing number of violent extremism and radicalism, the effects have baffled economies on national and international scales (Light & Thomas, 2020) . Although most terrorist acts occurred in countries amid violent conflict, many countries at peace were also affected (Clark et al., 2020) . As a result, radicalism has prompted a strong policy response, both in terms of counterterrorism and prevention efforts, in response to its spread (Clark et al., 2020) .

Understanding the economic effects of terrorism provides a solid foundation for assessing the number of funds that can be utilized on counter-terrorism initiatives and activities. Measuring the scope and expense of terrorism has significant consequences for evaluating its short- and long-term impact on economic activity. Estimating terrorism’s economic effect will assist policymakers in providing evidence for assessments such as cost-benefit analyses of terrorism prevention programs. Various literature discussed in this paper has examined the extent to which researchers have analyzed the economic effects of terrorism on both the local and global economies.

2. Dominant Theories/Hypothesis

Based on this literature review, psychology has yet to develop or discover any models and motivating factors that adequately explain aggressive behavior in explanatory and empirical models. The issue is not that researchers, academic institutions, and professionals have not yet tried to find such an explanation; the “ultimate goal” has eluded them. In essence, it is more reasonable to assume that the development of psychological theories to explain the cause of terrorism activities has received less attention, resulting in delayed advancement.

The psychoanalytic model is probably the most widely recognized theory that describes the causative factors of terrorism. However, this concept has flawed rational, conceptual, and qualitative underpinnings regardless of its impact on social science, history, and clinical psychology writers. For example, Sigmund Freud generalized aggression as a natural and intrinsic social phenomenon that most people should outgrow (Garofalo & Velotti, 2017) . From an ethological standpoint, Anderson and Bushman (2018) proposed that terrorism stemmed from a basic biological need. The authors claimed that the desire for antagonistic behavior is instinctive and that people only learn to express it through environmental exposure and interaction.

The theory of animalistic drive for violence is also evident in the literature. According to Garofalo and Velloti (2017) , this aggression develops over time and is often aggravated by empathic or neurophysiological stimulation, expelling it through catharsis, thereby reducing the urge to commit violence. Although anthropologists and other social scientists have unveiled significant differences in the nature and intensity of aggression across cultures and experimental research demonstrating that the environment can manipulate violence, both findings contradict a universal human instinct.

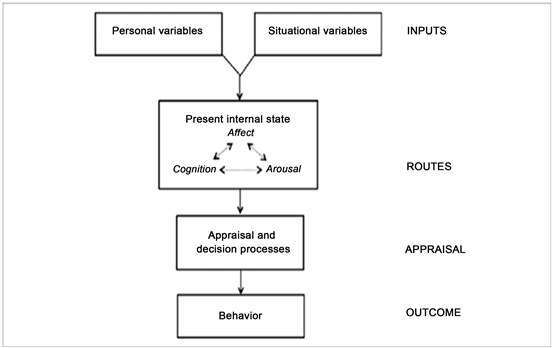

The drive theory, which links frustration and aggression, supports the literature. Some even consider it a “master explanation” for determining what causes human violence. For example, a common notion based on the Frustration-Aggression (FA) hypothesis is that frustration always causes aggression (Anderson & Bushman, 2018) . However, research has revealed that frustration only sometimes leads to an attack when put to the test. Instead, it can bring about problem-solving or dependent behaviors; for example, violence is known to happen without frustration (Anderson & Bushman, 2018; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2018) . As a result, considering frustration as a critical and sufficient causal factor is irrational (see Appendix A).

Terrorism is also exacerbated by neuropsychological factors that affect self-awareness and self-control. Evidence of the association between executive deficits and aggression has been found among incarcerated subjects, normal subjects in laboratory situations, and non-selected populations. The magnitude of the effects ranges from small to moderate, but they are consistent and reliable. Theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that prefrontal cortex dysfunction or impairment may be responsible for the psychophysiological deficits in individuals engaging in antisocial and aggressive behavior (Anderson & Bushman, 2018) . Indeed, numerous experts concerned with brain imaging, neurological, and animal studies posit that prefrontal dysfunction may account for low arousal levels, low-stress reactivity, and heroism.

3. Methods

The preponderance of researchers explored literature based on previous articles and related studies written by scholars to review the effects of terrorism on the economy. Identification of the relevant journals involved an electronic search using the terms “economic impacts of terrorism” as in the paper’s title. It restricted the examination to articles published within the last five years between 2016 and 2021. The initial results of the investigation yielded a total of 38 papers. Each journal was studied to determine if it has pertinent information about the impact of terrorism on global economics. Individual articles were carefully read to increase the review’s reliability, and 22 relevant journals were found.

In most of the peer-reviewed journals presented, the authors used a qualitative approach to reveal the underlying causes and patterns in feelings, beliefs, and motives. The information gathered helped clarify quantitative analysis theories and provided insight into the research issue. A quantitative method presented quantifiable data on the study goals, which was then converted into accessible statistics. The information was also helpful in quantifying attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors and identifying variables so that findings could be applied to a broader population. The survey design was suitable since it required both descriptive and inferential statistics. Therefore, it was appropriate to analyze respondents’ viewpoints on the impact of terrorism on the national and global economy.

Sample/Unit of Analysis

The literature focuses on the effects of local and international terrorism on national and global economies. Light and Thomas (2020) delve into how immigration plays a significant role in radicalism as people move from their home countries to foreign nations. This tendency results in inefficient resource allocation and stifles capital formation and economic development. Terrorism adversely affects local and global financial markets since it destabilizes the environment in which businesses thrive. As a result, real GDP per capita growth in targeted countries is frequently reported to be declining (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2018; Light & Thomas, 2020) . Furthermore, investor confidence is fading, resulting in a drop in FDI, a decrease in non-defense stock prices, and a drop in bilateral trade and tourism.

Further, terrorism is a non-revenue-generating frictional activity instigated by political, religious, or commercial problems. Governments must set aside funds to impede extremist movements, battle terrorist groups, and finance rescue and clean-up operations. However, the cost of violence is extremely high, and many countries have failed to execute appropriate counter-terrorism methods. Radicalism threatens the entire global economy, even though it is most prevalent in the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa (Böhmelt & Bove, 2020; Adamson, 2020; Féron & Lefort, 2019) . Terrorist groups, as seen in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia, will influence the local economy, neighboring states, and nations leading anti-terrorism operations.

4. Findings

Terrorism has claimed the lives of countless people all over the world. While the loss of human life is tragic, it is frequently held accountable for obscuring other societal consequences of terrorism. The most noticeable of these effects can be felt at the national and global levels of the economy regarding international economic cooperation. The IMF reveals that acts of terrorism have direct and indirect implications on government spending, which affect the economy (Coupe, 2017) . Direct costs impact an economy’s short-term nature, whereas indirect costs affect the economy over time as the business cycle progresses through its trajectories (Böhmelt & Bove, 2020; Adamson, 2020) . According to Light and Thomas (2020) , direct economic costs are directly proportional to the severity of the attacks and the economy’s size and characteristics, whereas indirect costs are primarily comparable. As a result, the economic impact of terrorism on an economy has direct and indirect financial outlays, impacting a nation’s economic well-being immensely.

For example, within the last 20 years, two noteworthy domestic terrorist attacks have had significant economic consequences. The first attack was Al Qaeda’s and Osama Bin Laden’s attack on America’s financial and military symbols, which destroyed the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center in New York City, and the Pentagon attack. The domestic terrorist attack resulted in the casualties of approximately 3000 human beings (Light & Thomas, 2020; Okafor & Piesse, 2018) . The incident paralyzed Manhattan’s financial district for six days before reopening on 17 September 2001. Coupe (2017) reveals that the second major terrorist operation was the Paris attacks on 13 November 2015, which shocked Paris and the European Union, prompting increased security measures. A series of three attacks targeting a major football stadium, an active city square, and a famous theatre sparked panic in Paris, prompting France to close its borders for a while. In addition, the attack resulted in baffled trade and free movement within Europe.

Terrorism’s direct economic costs are most pronounced in the immediate aftermath of attacks and, thus, matter more in the short term. Unprecedented expenditure on outcomes such as loss of life and property, emergency response, restoration of damaged systems and infrastructure, and temporary living assistance restrain the national budget (Okafor & Piesse, 2018) . Direct economic costs are likely proportional to the attacks’ severity and the affected economy’s size and characteristics (Chaudhry et al., 2018; Coupe, 2017; Okafor & Piesse, 2018) . Following the 9/11 attack, travel and tourism-related businesses, particularly stocks related to the travel industry, took a significant hit, resulting in billions of dollars in losses and a substantial drop in stock value.

For instance, the stock value of popular travel website Expedia fell by 2.7 percent, Delta Airlines fell by 0.84 percent, and American Airlines Group’s stock value remained unchanged (Light & Thomas, 2020) . While a drop in travel stocks is an expected reaction to the violent events, the longer-term economic damage was caused by fearful consumers who were much less likely to fly or travel. In addition, the United States government restricted border entry (Coupe, 2017) . Tighter borders and lower consumer spending had dangerous consequences for the United States as consumer spending was a critical factor in GDP calculation and impacted it directly.

The US GDP, which grew much slower from 2001 to 2002 than from 2000 to 2001, demonstrated this impact. According to Silva et al. (2020) , the US decision to tighten entry restrictions from other countries resulted in significant GDP loss, as immigration into the country slowed, and fewer taxpayers resulted in lower government spending. In the aftermath of the violence in Paris, one can see similar results of terrorist attacks. Since trading routes that ran through France were temporarily closed due to the attacks, the entire European Union’s economy was baffled (Coupe, 2017) . Before the attacks, the European Union was in serious trouble. The whole zone grew by only 0.3 percent in the third quarter of the fiscal year, well below economists’ expectations worldwide (Masinde et al., 2016) . Silva et al. (2020) argue that the 9/11 attacks directly impacted current spending and deterred shoppers from spending in crowded retail areas before the busiest season when people flock to the markets for festive activities and holiday shopping.

While this decrease in spending has not been visible in the economy for some time, France’s GDP is still expected to decline. However, the drop may be more significant than in the US, mainly since most of France’s economy is based on tourists visiting the famous romantic city of Paris or the French Alps. Coupe (2017) speculates that France’s GDP will fall significantly without these services’ critical revenue. Corbet et al. (2019) unveiled that there is yet to be pure numerical evidence of the impact. However, statistical evidence suggests that British shoppers stayed home in the weeks following the Paris attacks and avoided visiting retail markets. Most of Europe was on terror alert, with several threats against European cities occurring in the weeks following the bombings (Coupe, 2017) . While this fear will fade if the country is not terrorized for long, another medium-term damage may significantly impact the European Union.

Terrorism activities also have a profound impact on the stock markets of the targeted nations. According to Chaudhry et al. (2018) , violence causes an external shock to the economy, resulting in short-term and long-term effects. Significant evidence shows that an extremist attack on one nation can affect another country’s stock market due to economic integration. For example, the attacks on 9/11 impacted the major industrial countries, mainly in Asia and Europe, due to decreased demand caused by a loss of confidence, which affected their ability to produce enough to meet their own economic needs (Chaudhry et al., 2018) . Today’s global economy is deeply integrated, so each country’s stock market interlinks with another nation to enhance international trade and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

Developing countries were harmed as external demand fell, and industrial countries’ production costs rose to the point where providing resources to emerging markets became increasingly difficult. However, following the immediate direct and short-term indirect expenses, the attacks on 9/11 could regain strength quickly (Chaudhry et al., 2018) . The attempt to completely cripple the US economy failed due to the country’s market’s resilience; however, it is safe to say that its economy was not the same in GDP growth a few years after the attacks, owing to the direct costs of the attacks. Moreover, the US’s ability to recover quickly was hampered by significant activity disruptions caused by considerable damage to property and communication systems (Chaudhry et al., 2018) .

The government and personal transactions had to be cleared manually, causing significant delays and numerous compelling investors to liquidate their assets due to the uncertainty of recovery. In addition, essential markets were unable to trade due to infrastructure damage. This scenario, combined with society’s reluctance to deposit money in banks, resulted in a reduction in the money supply in the immediate aftermath, prompting abrupt government intervention before hyperinflation could occur (Chaudhry et al., 2018) . Furthermore, a series of problems, including banks refusing to execute payments due to shortages in the United States Federal Reserve, further worsened the economy at both local and international levels.

Insurance companies also suffer massive losses in case of a terrorist operation. Tavor and Teitler-Regev (2019) confirmed that violence causes many injuries, creating an urgent need for medical care. For example, in the United States, domestic terror attacks resulted in massive property losses and medical requirements for casualties that exceeded 50 billion dollars (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2018) . According to Tavor and Teitler-Regev (2019) , the stock exchange was closed and opened six days later due to the massive infrastructure and communications damage. Other economic areas that have been affected include free mobility. Today, citizens cannot travel easily between countries due to stringent border controls, including rigorous background checks.

Terrorism has high indirect costs that can drastically alter a country’s or region’s economic landscape. According to Zakaria (2019) , investor and consumer confidence are harmed due to this impact. Investors become reluctant to put their money into an economy in jeopardy, where unprecedented terrorist events could lose real estate or infrastructure investments. Once consumer confidence has been shattered, as seen in the aftermath of the Paris attacks, there is little chance that investors, unless compelled by the government, will invest in a market where consumerism does not exist (Zakaria, 2019; Ajogbeje et al., 2017; Seabra et al., 2020) . This state of affairs erodes consumer confidence, reducing people’s motivation to spend rather than save. Iqbal et al. (2019) argue how the effects of low consumer confidence can spread worldwide through the normal business cycle and international trade channels due to the integration of global finance networks. Besides, a lack of investor confidence combined with low consumer confidence causes stocks to fall far below expectations to entice anyone to invest (Ajogbeje et al., 2017; Samitas et al., 2018) .

Time, the nature of attacks, types of policies adopted in response to the terrorist invasions, and the guidelines to kick in when the market begins to influence the magnitude and distribution of this effect across countries and regions. Bandyopadhyay et al. (2018) reveal that violence incurs vast amounts of money in infrastructure and communication, which shatters a country’s financial system and affects consumer and investor confidence. This situation limits a country’s ability to shift its production curve, adversely affecting its GDP. Consequently, the frequency of terrorist operations in a particular area determines the magnitude of financial impact.

Bassil et al. (2019) argue that persistent terror threats may result in permanent economic costs. Many governments have long-term plans and implement fiscal policies to sustain the additional cost of security. For instance, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict costs the former approximately 4% of its GDP (Bassil et al., 2019) . Another study established that conflicts within Palestinian territories resulted in a 50% decline in the country’s GDP between 1992 and 2003 (Bassil et al., 2019) . In a similar study focusing on low- and middle-income countries, Corbet et al. (2018) established that additional fiscal cost of security resulted in direct and indirect adverse effects on economic growth. Such developments have negative implications for government spending and the confidence of investors.

5. Future Research Gaps

The literature review provided a global analysis of terrorism, concluding that suicidal operations executed by terrorists today have devastating effects on the economy regardless of the level of preparedness a country may assume. However, since the causes of violent attacks differ among locations, the articles utilized in this paper did not define or identify any exact sources. Most authors focused on the effects of terrorism on countries’ economies without giving much attention to other factors, such as religion, which is a critical driving force in terrorism. Although many doctrines promote peace, it is unclear whether some religious leaders use them to perpetrate violence.

The studies reviewed demonstrated how terrorism harms the economy. The analysis also reveals how the approaches used to fight terrorism have adverse effects on the fiscal status of a nation. However, they fail to provide effective means of fighting terrorism to have a minimal economic impact. Terrorism often triggers civil unrest and the inflow of illicit funds into a country, resulting in inflation. However, the articles under review make no recommendations for dealing with or reversing such tendencies. Young Muslim elites were known to pursue Islamic education in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan in the 1970s, which marked the start of radicalization in most countries, especially in the developing world. Nonetheless, the latest terrorist activities are probably homegrown and have little to do with Muslim returnees.

The literature review also reveals that some youths were recruited after hearing notorious preachers such as Aboud Rogo and Makaburi. They urged Muslim children to join the jihad in Somalia and fight against infidels. Unknown assailants killed the felons after the government took no action against them. It is unclear why, other than murder, no other legal procedures could be imposed on individuals who incited youth to join militant groups to commit violence. These factors contribute to the gaps that this study aims to fill.

In addition, researchers need to address the lack of literature distinguishing terrorism and Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs). The current studies do not draw a clear line between these two variables but treat them as one item. Since terrorism is often referred to as the illegal use of force that destroys property and injures or kills human beings, terrorism remains a judgmental term with no universal definition (see Appendix B). Each global community tends to understand it from a perspective that reflects specific interests and priorities. In contrast, violent extremism is a more complex activity fueled by complex organizations for political, economic, or religious reasons (see Appendix C). Therefore, it is noteworthy that minimal research differentiates the two terms while leaving researchers and actors concerned with national defense using them interchangeably. In this manner, drawing a clear line between terrorism and violent extremism will create a path for researching radicalization at the micro level.

6. Conclusion

Researchers are recommended to distinguish between violent extremists and terrorism to help policymakers determine the depth and intentions of extremist activities. The literature review unveiled how some authorities charged with protection against violence do not differentiate the two issues.

Terrorism-related deaths, accidents, collateral damage, and GDP losses are all factored in the literature reviewed. Between 2003 and 2018, extremist groups’ violent activities adversely affected many countries, such as Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, France, the United States, and a few countries in the developing world, including Somalia, Nigeria, and Kenya. As a result of the US invasion of Iraq, accompanied by waves of high-intensity wars, Iraq was most affected by terrorism for 14 of the 15 years from 2003 to 2018 (Iqbal et al., 2019; Tavor & Teitler-Regev, 2019; Samitas et al., 2018) . Following the defeat of ISIL in 2014, the level of extremism in Iraq has decreased. Iraq, on the other hand, remains one of the world’s most terrorist-infested nations. Afghanistan surpassed Syria and Iraq as the region most afflicted by terrorism in 2018. As a result of continuing conflicts between Taliban, ISIS, and government forces and reduced foreign troops.

In 2018, the economic effects of terrorism in Afghanistan hit 22% of the GDP (Iqbal et al., 2019) . Terrorism has had the most significant impact on the Middle East and North Africa. Since 2000, the economic burden of terrorism in the country has totaled 434 billion US dollars (Iqbal et al., 2019; Samitas et al., 2018) . Sub-Saharan Africa was the second most affected country, with 133 billion US dollars in damages. South Asia is the third most affected country, with an economic impact of 125 billion US dollars (Iqbal et al., 2019) . In South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa, armed attacks and gunfire result in adverse economic effects due to citizens’ mass execution and property destruction. Therefore, implementing measures to prevent such attacks as disarmament or bomb detection may help reduce terrorism-related violence and its associated costs in these three areas.

Researchers use various methods to assess the magnitude of the effects of violence. For example, Samitas et al. (2018) used a vector regression model to investigate the impact of terrorism on FDI using data collected from Greece and Spain. The study established that terrorism had a negative 11.9% impact on FDI in Greece between 1975 and 1991 and a 13.5% impact on Spain’s FDI between 1976 and 1991 (Samitas et al., 2018; Desai, 2017) . In a similar study focusing on several countries, the authors established that terrorism decreased FDI by 4.16 to 6.54% based on a Global Terrorism Index (GTI). As a result, government spending focused on boosting the FDI and domestic investment in counter-terrorism measures to mitigate actual or perceived terror threats.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my special appreciation to my committee member and chair, Dr. Ian R. McAndrew, FRAeS, Dean, Doctoral Programs and Engineering Faculty. I am grateful for Dr. McAndrew’s timeless support in encouraging my research and writing to continue developing as a scientist. In addition, his advice on research and academia has been priceless. I would also like to thank Dr. Ron Martin and Carmit Levin for their enduring support. Also, thanks go to my cousin, Ms. Maria Boston, whom I was recently reunited with after 34 years of separation. Maria’s family sacrifices as a single parent did not go unnoticed, and her academic inputs were invaluable.

Appendix A. The General Aggression Model (GAM)

Note: Adapted from Anderson (n.d.) . Effects of Weapons on Aggressive Thoughts, Angry Feelings, Hostile Appraisals, and Aggressive Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Weapons Effect Literature—Scientific Figure on Research Gate. [Review of Effects of Weapons on Aggressive Thoughts, Angry Feelings, Hostile Appraisals, and Aggressive Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Weapons Effect Literature—Scientific Figure on Research Gate]. ResearchGate. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-General-Aggression-Model-GAM-Source-Anderson-and-Bushman-2002-Krahe-2013_fig1_319878868.

Appendix B. Definitions of Terrorism

Note: Adapted from Staff (2017) , Project Gecko. Retrieved January 22, 2023, from https://www.projectgecko.info/security-articles/2017/10/2/defining-terrorism.

Appendix C. Countering Violent Extremism

Note: Adapted from United States Government Accountability Office (2017) . Countering Violent Extremism: Actions Needed to Define Strategy and Assess Progress of Federal Efforts. Report to Congressional Requesters, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-300.pdf.