Evaluating the Triadic Relationship between the Armenian Diaspora, Armenia’s Cultural Identity, and the Artsakh War: Toward a Sustainable Map of Peace ()

1. Background

The Artsakh War is an ethnic, religious, and territorial conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed region of Artsakh, an Armenian enclave within Azerbaijan (Payaslian, 2007; Tamzarian, 1994). Of Artsakh’s 145,000 inhabitants, 95% are Christian Armenians. On February 20, 1988, the Soviet government passed a resolution requesting transfer of Artsakh from Azerbaijan to Armenia. Azerbaijan rejected the request, and ethnic violence against Armenians began. The dispute escalated into a full-scale war in the early 1990s. For three decades, multiple violations of the ceasefire have occurred. The latest escalation began on September 27, 2020.1 Numerous countries and the United Nations (UN) called on both sides to deescalate tensions and resume meaningful negotiations. A humanitarian ceasefire brokered by Russia and the International Committee of the Red Cross, and agreed upon by both Armenia and Azerbaijan, came into effect on October 10, 2020. On November 9, 2020, Armenia’s Prime Minister signed an agreement with the Presidents of Azerbaijan and Russia to end the war in Artsakh. Under this agreement, Azerbaijan retained control of land within Artsakh that it has already captured, and Armenia agreed to relinquish adjacent land in the now Azeri-occupied areas.2

International Law

Protecting the rights of the people of Artsakh is a major concern for Armenia. Under international law, minority groups that qualify as “peoples” are entitled to self-determination, or the ability to freely determine their political fate and form a representative government. The principle of self-determination assumes that secession is necessary when the seceding people are oppressed or when the government has failed to represent the people’s interests. Article 1 of the UN Charter, which states that one of the purposes of the UN is, “to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples,”3 and two UN declarations: the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries4 and the 1970 Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations5, have addressed self-determination.

The international community neither recognizes Artsakh as an independent state nor as part of Armenia. Indeed, the European Union (EU) and its member states, the UN, the United States (US), and the European Court of Human Rights all recognize Artsakh as Azeri territory. This recognition is important because territorial affirmation by the international community would be persuasive if a legal argument was constructed in favor of formal annexation of Artsakh to Armenia. Here, however, few non-Armenian entities believe that Artsakh is part of Armenia, which suggests that the Armenian position is likely without legal justification.

There is support that Artsakh is recognized as its own state entity. First, the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States6 established a standard definition of statehood under international law. Under Article 1 of the Convention,7 a state should possess the following characteristics: a permanent population, a defined territory, a government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other states. Article 3 of the Convention represents the declarative theory of statehood, while “the political existence of the state is independent of recognition by the other states.”8 This theory of statehood stands in opposition to the constitutive theory of statehood, which holds that a state exists only when it is recognized by other states. It is important to note that while Artsakh does have a permanent [Armenian] population, a defined territory, its own government, and presumably could enter into relations with other states, the Montevideo Convention is persuasive authority at best, given its regional focus and the fact that neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan are signatory parties.

Second, the US has had an annual foreign aid appropriation earmarked directly for Artsakh for three decades. Congress has allocated aid for general development and humanitarian purposes, such as infrastructure, agriculture, and medical projects. Artsakh also receives aid indirectly from the United States. The US is Armenia’s largest bilateral aid donor, with a sizable portion of the annual Artsakh budget coming from direct Armenian appropriation.

Culture and heritage shape values, beliefs, and aspirations, defining a people’s identity. The importance of cultural heritage is not the manifestation itself but rather the wealth of knowledge that is transmitted and preserved from one generation to the next. While the importance of preserving a nation’s heritage cannot be understated, the ability to maintain one’s cultural identity should be weighed against the tangible costs associated with a protracted military conflict. A methodical approach to peacemaking may offer the opportunity to enhance the Armenian heritage and pursue cultural humility while acknowledging that cessation from Artsakh offers the opportunity to create a culture of peace.

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Intractability

Rather than being characterized by a single violent episode, an intractable conflict involves hostile relationships that extend over time and occasional military action (Coleman, 2011; 2006). Intractable conflicts “attract the involvement of many parties, become increasingly complicated, give rise to a threat to basic human needs or values,” … and “result in negative outcomes for the parties involved …” (Coleman, 2006: p. 533). Intractability acts as an integrating concept, depicting processes where states become enmeshed in a web of negative and repetitive interactions and hostile orientations. A relatively small number of conflicts are “intractable,” but most appear to exist within the international area (Coleman, 2011), where, not surprisingly, a labyrinth of individual, governmental, historical, religious, ethnic, and environmental factors influence, and often magnify, the intransigency.

There are five characteristics of an intractable conflict (Coleman, 2006): 1) an unbalanced power relationship; 2) structural contradictions that are not easily resolvable; 3) the relationships between the disputants are characterized by stereotypical images, discrimination, and historical oppression; 4) dehumanization of the enemy created by ethnocentric processes and cognitive rigidity; and 5) prolonged trauma and normalization of hostility. Based on these characteristics, the Artsakh War is intractable. First, there is an unbalanced power relationship. Armenia is a Christian, landlocked nation bordered by Turkey to the West and Azerbaijan to the East with a history of significant victimization at the hands of both nations. The Daisy model and conflict map illustrate the primary (Armenia and Azerbaijan), secondary (Iran, Turkey, Syria, Georgia, Serbia, militias, and the Armenian and Azeri diaspora), and tertiary actors [Russia, the US, the UN, and non-governmental organizations] in the Artsakh conflict and demonstrate the unbalanced quantity of alliances. Second, structural contradiction theory argues that conflicts generated by fundamental contradictions in the structure of society produce laws defining certain deviant acts as criminal. Here, economic (oil pipelines and arms trafficking) and political/legal (OSCE Minks Group and international law) are implicated. Third, there is mutual distrust and discrimination between Armenians and Azeris and between Armenians and Turks which has its roots in the historical oppression of Armenians by the Ottoman Turks. Fourth, Armenians are a Christian nation dedicated to the preservation of democratic ideals and human rights, while Azerbaijan and Turkey are Islamic with long histories of persecuting ethnic minorities within their borders. Fifth, the Artsakh conflict has its roots with the annexation by the Soviet Union, post-war agreements, and modern military engagement for the past thirty years. These last three intractability characteristics are illustrated in the conflict map as historical, military, and environmental dynamics.

2.2. Power and Conflict

Power is “a mutual interaction between the characteristics of a person and the characteristics of a situation, where the person has access to valued resources and uses them to achieve personal, relational, or environmental goals, often through using various strategies of influence” (Deutsch & Coleman, 2000: p. 113). Here, Azerbaijan’s “access to valued resources” includes the physical location of Artsakh within its geographic boundaries, the Russian alliance, and support from the international legal community. These disparate resources thus reflect a power imbalance among the parties (Weitzman & Weitzman, 2006). While the Artsakh enclave is populated primarily by Armenians, Azerbaijan enjoys “structural power” (Lewicki et al., 2016: p. 193; Moore, 2014: p. 149) because the territory lies within Azerbaijan and the non-Armenian international community recognizes that Armenia has no cognizable claim to the territory. This power imbalance has led to a “power over” orientation because the competitive goal of controlling the Artsakh region has ultimately caused the disputants to attempt to maximize their own goals (Lewicki et al., 2016: p. 196). These power dynamics are critical to understanding how Armenia and Azerbaijan may respond to outright refusals to negotiate. Azerbaijan, with its structural power, may simply move forward with military offensives, while Armenia looks to its diaspora for humanitarian and military support as it seeks to increase leverage and bargaining power (Lewicki et al., 2016: p. 200).

2.3. Peace Psychology

According to Christie et al. (2008: p. 544), “the potential for a violent episode exists when the predominant state of a relationship is conflictual.” Moreover, realistic group conflict theory suggests that hostility is likely to occur when groups are in competition for scarce resources (Sherif & Sherif, 1953). These two propositions characterize the relationship between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the context of the Artsakh War. The formation of the Soviet Union after the First World War often pitted Republics against each other, with Russia serving as the natural mediator. In addition, the Artsakh enclave itself (i.e., land) is the scarce resource, particularly for two nations whose territories are relatively small in a region characterized by volatility.

De-escalating the violence in a protracted conflict like Artsakh would require the parties to work toward mutually satisfying outcomes. Here, however, the “zero-sum” outcome (Deutsch, 1973) characterizes the conflict, where sole occupation of the Artsakh enclave is the goal of both sides. Intractable conflicts that are punctuated by violent episodes may sometimes reach a point where both sides are unhappy with the violent relationship and neither side is close to achieving its goal. This stalemate is absent here, however, because Armenia recently ceded parts of Artsakh to Azerbaijan. If Azerbaijan is convinced that continuing the conflict will engender long-term benefit (i.e., acquiring more territory in Artsakh), then the situation is likely not ripe for the introduction of peacemaking initiatives (Coleman, 2004).

2.4. Intergroup Processes

Unlike cooperative relations, where the goals of the parties are positively independent, a competitive process is characterized by impaired communications, mutual suspicion, coercion, and attempts at amassing power (Deutsch, 2006). According to Deutsch (2006: p. 28), the competitive process may result in “autistic hostility” (ceasing communications); “self-fulfilling prophecies” (preemptive hostilities based on a false narrative); and “unwitting commitments” (committing to rigid positions and to negative perceptions of the adversary). Given the length of the conflict, and the engagement of outside nations whose histories are antithetical to peace, the Artsakh War is clearly competitive. Because the conflict has, for more than 30 years, been viewed as a win or lose struggle, the process can be characterized as “destructive” (Deutsch, 2006: p. 32). The keys to addressing such a destructive process would be to recalibrate to a “cooperative orientation” and to “reframe the conflict as a mutual problem to resolved (or solved) through joint cooperation efforts” (Deutsch, 2006: p. 34). It would be important, for example, to appreciate that Armenia and Azerbaijan, as two relatively small former Soviet republics, should both be dedicated to preserving their cultural identities rather than engaging in war, which causes significant financial strain and mass human casualties for two second-world nations.

2.5. Distributive Bargaining and Integrative Negotiations

Distributive bargaining is a competitive approach that promotes win-lose situations, where one party attempts to gain the maximum amount by using power to force the adversary into agreement (Lewicki et al., 2015). Distributive bargaining is framed as a competitive event, where the winning party tests the limits of the losing party during negotiations. In contrast, integrative negotiations follow a collaborative path that allows both sides to emerge as victorious. Integrative negotiations go beyond each side’s positions and focus instead on identifying and prioritizing the underlying interests behind the positions (Lewicki et al., 2015). Integrative approaches strive to make the environment conducive to exchanging information. Rather than one side forcing authority on the opposing side, thoughts and ideas are shared and information and perspectives brought to light.

With respect to Artsakh, I am aware of no attempts to resolve the conflict with a permanent peace treaty. Given the duration of the conflict, its intractability, and Armenia’s subservient geographic, political, and military position, integrative negotiations seem to be the most suitable approach. That said, there are two drawbacks to this approach when the conflict is characterized by human rights violations and significant power asymmetries: 1) holding perpetrators accountable for human rights violations may lead to the further “splintering” of society; and 2) addressing the structural violence and power asymmetry may dwindle, particularly for the victorious party, after the conflict subsides (Babbitt, 2014). Here, the 2020 ceasefire resulted in Armenia proper agreeing to the relinquishment of all territory in Artsakh that Azerbaijan had captured at the time of the ceasefire.9 There is nothing to prevent Azerbaijan from renewing hostilities to secure Artsakh in its entirety (Yacoubian, 2021).

2.6. Multicultural Conflict Resolution

A revolutionary change in world politics has been a de facto redefinition of “international conflict.” The range of epoch-making changes includes democratization, globalization of information and economic power, international coordination of security policy, violent expressions of claims to rights based on cultural identity, and a redefinition of sovereignty that imposes on states new obligations to their citizens and the world community (Ruggie, 1993). The cultural identity development model “emphasizes the complexity of culture and the changing character of multiculturalism” (Pederson, 2014: p. 655). The greater the cultural differences between parties in a conflict, the more difficult it will be for them to communicate and appreciate the position of their adversary (Pederson, 2014).

Culture is a crucial factor in shaping identity. Because one of the main characteristics of a culture is its “historical reservoir” (Pratt, 2005), many if not all groups entertain revisions in their historical record in order to bolster the strength of their cultural identity. This is no more evident than the Turkish denial of the 1915 Armenian Genocide. By claiming that the 1.5 million Armenian who perished during the genocide were “victims of war” (Yacoubian, 2010), the Turks distanced themselves from their violent history and thereby buttress a cultural identity of neutrality. Similarly, evidence suggests that the Artsakh conflict in 2020 was initiated by Azerbaijan and that Azeri forces targeted civilians, in violation of international law.10 This is a reasonable conclusion given the unlikelihood that Armenia would initiate conflict to retain land it currently occupied.

3. Data Collection

Literature Review: Theories

There are several ways data could be collected to test the power and conflict theory, which I believe is the most salient of the theories identified. First, a content analysis of secondary sources (books, social science periodicals, and law review articles) could be analyzed to examine the relationship between Russia and two of its former Soviet republics, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Content analysis is distinguished from other types of social science research in that it does not require the collection of data from people but rather is the study of information that has been recorded in text. It is a method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). There are three types of content analysis: conventional qualitative content analysis, directed content analysis, and summative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Conventional qualitative content analysis is a process whereby coding categories are derived directly and inductively from the raw data. The second approach is directed content analysis, in which initial coding starts with a theory or relevant research findings. The third approach, summative content analysis, starts with the counting of words or manifest content, then extends the analysis to include latent meanings and themes. Here, conventional and summative content analyses could be used to explore the extent to which Russia’s relationship may be stronger with Azerbaijan than with Armenia, which would put Armenia in a precarious power imbalance.

Second, a content analysis of current treaties could be examined to explore the current political, economic, and military relationships between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the primary actors in my Conflict Map, and the secondary and tertiary actors identified in the Conflict Map. Conventional/treaty relationships would indicate, first, not only the quantity of interactions between the parties across multiple spectra, but the strength of the relationships, as evidenced by the types of treaties into which the primary and secondary/tertiary actors have entered. Treaties involving energy interdependence and military cooperation would be perceived as stronger and more important that a treaty that addresses a non-controversial topic like child protection.

Third, qualitative interviews could be conducted with key stakeholders in Armenia to assess their perceptions of the current conflict and the extent to which they perceive Armenia as sufficiently power imbalanced so as to require capitulation. A stakeholder is an individual or group that has an interest in a decision, activity, or conflict. Disaggregating “Armenia,” stakeholders include governmental officials (President, Prime Minister and Judicial and Legislative bodies), military personnel, Armenian citizens living in Artsakh and Armenia proper, the Armenian diaspora, and humanitarian organizations that provide relief to those impacted by the conflict.

War begins and ends by key decisionmakers deciding to initiate, perpetuate, or withdraw from conflict. These key government officials are elected by the populace to safeguard Armenia’s sovereignty. The decisions made by government officials as it relates to the War are presumably influenced by the recommendations of military personnel, who are skilled to assess the likelihood of victory or defeat. Military personnel would take into consideration the quantity of available Armenian soldiers relative to those of Azerbaijan; the training of the military; available weaponry and ammunition; economic capabilities of sustaining a protracted conflict; the ability to procure additional and different weaponry; the medical infrastructure to assist injured front-line personnel; and the calculus of human casualties. Governmental and military personnel could also provide significant insight into Armenia’s military capabilities and perceived relationships with other countries that offer military support.

Armenian citizens living outside of Armenia are a significant source of emotional and financial support for their homeland. These stakeholders would be charged with knowing and disseminating accurate and timely information on the conflict to Armenians around the world and to providing financial support for all of the operations impacted by the War. This financial support includes money for weaponry, front-line equipment, medical supplies, humanitarian assistance for displaced families, and resources for rebuilding. Humanitarian organizations, like the Society for Orphaned Armenian Relief (SOAR),11 provide significant humanitarian assistance to families displaced by the War, to orphaned children who were relocated from Artsakh to Armenia proper, and to the families of Armenian soldiers killed in battle. Families and orphaned children displaced from the War could be interviewed about their perceptions of the war, the short- and long-term impact that the conflict has had on them, and the extent to which they believe that Armenia should permanently relinquish Artsakh and relocate its Armenian populace to Armenia proper.

4. Bridge to Intervention Strategies

Because power imbalances characterize all relationships, operationalizing and testing power theories should help focus on future conflict analyses. That said, it is important to appreciate the breadth of the Artsakh War and how the conflict continues to shape the lives of the primary actors and the key stakeholders who are indirectly impacted by the protracted nature of the War. Because diasporan Armenians generally consider Armenia to be their ancestral homeland, they take a vital interest in geopolitical or military conflicts that threaten survival. The characteristics of the Artsakh conflict suggest a complicated tapestry of discord. Taken collectively, theories of power and conflict, peacemaking psychology, intractability, intergroup processes, distributive bargaining and integrative negotiations, and multicultural conflict provide a wider lens from which to appreciate the nature of the conflict and, more importantly, potential peace-building solutions.

A structured approach to conflict analysis is essential to examine the causes and nature of the Artsakh War. After a thorough review of the major concepts that characterize the War, particularly power imbalances, intractability, and intergroup processes, Armenians in Armenia and the diaspora must acknowledge that the populational presence of Armenians in Artsakh does not, in and of itself, entitle it to geographical sovereignty. That is, peace in Artsakh is unachievable until Armenia, first, acknowledges that its claim to the territory is not grounded in legal reality, and second, acquiesces to the reality that violence to retain Artsakh offers no long-term hope to the perpetuation of its cultural legacy.

To facilitate and maintain permanent change (peace) in Artsakh, I have considered several resolution strategies. First, the Collaborative Loops process “brings together dissimilar project teams … to develop their own strategies” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 114). This process involves the conflict disputants coming together to use their own experiences as the basis for change. Here, I consider the citizens of Armenia and Azerbaijan as the actors who might come together, independent of their respective government and military actors, to discuss the impact the Artsakh war has had on their daily lives. If a strong majority of the citizens of both countries want the conflict to end, sustainable change might be possible.

Whole-Scale processes “facilitate systems-wide change … in a wide variety of countries, cultures, and organizations” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 165). The first step in using Whole-Scale processes is to clearly define the strategic purpose of the effort. Here, the purpose is to achieve permanent peace in Artsakh. To achieve this goal, Whole-Scale must, first, “understand both its history and its present state to create its future” and “focus on the interconnectedness of people, processes, and technology” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 170). The Whole-Scale process would require bringing together not only the government entities who ultimately coordinate all decisionmaking, but the actors who are directly and indirectly impacted by the war in Artsakh (e.g., the surviving spouses of Armenian soldiers killed in battle) so that the conflict’s reach can be appreciated by everyone. This process would necessarily involve the Armenian diaspora, whose influence and attachment to Armenia military history has facilitated continuation of the Artsakh War.

The goal of Scenario Thinking is to “arrive at a deeper understanding of the world” in which an organization or community operates and “to use that understanding to inform your strategy and improve your ability to make better decisions today and in the future” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 332). Scenario Thinking helps decisionmakers “order and frame” their thinking about the distant future, while providing them with the “tools and the confidence to take action soon” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 332). Here, the reflective thinking process would allow the Artsakh actors to think about what is to be achieved by continuing the conflict and why that long-term goal (e.g., obtaining or retaining land) is so important. If the long-term implication for the Artsakh conflict is cultural survival through the retention (Armenia) or accumulation (Azerbaijan) of land, then the disputants may consider other non-military opportunities and strategies to perpetuate their respective cultures and to maintain their unique heritages.

Intervention strategists use different methods to resolve conflict, and most people have one or more preferred conflict resolution strategies that they prefer to use. The ultimate goal of intervention is change, which can be facilitated at the actor level (e.g., the disputants), at the structural level (e.g., economic) or at the contextual level (e.g., cultural prioritization among ethnic diasporas). It is thus critical to be equipped with the most appropriate intervention strategies to intervene systemically (i.e., to impact as many levels as possible). In this section, I highlight three specific needs for Armenia and Azerbaijan in the context of the Artsakh War: 1) physical survival and safety; 2) cultural survival, or the perpetuation of their respective cultural heritages; and 3) the reductions of short- and long-term harm. I describe these needs and offer intervention and risk management strategies for each.

4.1. Physical Survival and Safety

Armenia is a second-world nation (i.e., a former Soviet Republic) that relies on significant economic assistance from its diaspora and the international community. There is a sizeable disjuncture between and among economic classes in Armenia, a relatively small upper class with most Armenians living below the poverty line. For vulnerable and marginalized populations, the economic detachment is even more pronounced. According to 2017 data from the Asian Development Bank, 26% of Armenia’s population lived below the poverty line in 2019.12 The unemployment rate, according to 2020 data, is 20%.13 According to UNICEF, 64% of children are “multidimensionally poor,” and 37% of children are monetarily poor (Ferrone & Chzhen, 2016). Almost one in three children is both poor and deprived, while 28% of children are deprived (in two or more dimensions) and live in monetarily poor households (Ferrone & Chzhen, 2016).

Holman et al. (2007: p. xi) offer a variety of intervention strategies that merge “theory and best practices from a variety of disciplines.” Intervention strategies devise a plan of action that outlines methods, techniques, programs, or tasks to successfully complete a specific goal or need. Maslow (1943) theorized that all humans have five levels of needs to be satisfied, with the most self-fulfilled individuals being able to obtain and retain all five of these needs. He saw these needs hierarchically, a list of ideas, values, or objects from the lowest to the highest (Maslow, 1943). The first and most basic need is related to physical survival (Maslow, 1943). This is the need for food, drink, and shelter. If a person cannot satisfy these basic needs of nutrition and shelter, they cannot socialize, learn, work, or survive. Once the physical survival needs are met, a person becomes aware of the next level of human need, physical safety (Maslow, 1943). This is the need to feel safe from personal danger and threats within one’s community, country, and the world. Being exposed to physical danger, such as the threat of war, results in fear. When a person is fearful, all concentration goes to addressing the fear. Human development requires freedom from fear of personal attack, particularly in one’s closest environments (e.g., home and country).

To address the first need of Armenia’s physical survival and safety, I explore Whole-Scale processes, which “facilitate systems-wide change … in a wide variety of countries, cultures, and organizations” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 165). The Whole-Scale process involves comprehensive change and a mutual understanding of what is desired. The first step in using Whole-Scale processes is to clearly define the strategic purpose of the effort. Here, it will be important to bring together Armenians in Armenia and across the diaspora to explore constructs related to food and nutrition access; proper hygiene; economic self-sufficiency; land, property, and shelter; and perceptions of danger and fear.

This Whole-Scale process, by coming to a mutual understanding and “reaching agreement on action plans” (Holman, et al., 2007: p. 166), can narrow the gap between what Armenians in the diaspora expect to achieve and the ability for Armenia to achieve physical survival and safety. It is important to understand that Whole-Scale change is not a singular event. Rather, it is a “never-ending journey” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 168), an iterative process that involves the continual sharing of ideas among stakeholders and those impacted by systemic decisionmaking. To be successful, the Armenian diaspora will need to recognize that the physical survival and safety of Armenia is hindered by active military hostilities, particularly in a state whose economic and medical infrastructure may not be equipped to adequately address significant human casualties.

The guiding principles of Whole-Scale change include a thorough understanding of history and the present to best plan for the future and the “interconnectedness of people, processes, and technology” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 170). There may be a disjuncture between what Armenians in the diaspora perceive as beneficial for Armenia proper and what Armenians in Armenia and Artsakh perceive as advantageous for Armenia’s physical survival and safety in the long-term. Armenians in the diaspora may be more concerned with the retention and preservation of land (Artsakh and Armenia proper), while Armenians in Armenia and Artsakh may be most concerned with access to food, clean water, and shelter. While all of these needs are related to physical survival and safety, prioritization may forge a deeper understanding of their interconnectedness. Bridging this gap and devising collaboration among Armenians, in and out of Armenia, will be a critical first step. It is important to understand how all Armenians define physical survival and safety, how they prioritize the constructs associated with physical survival and safety, and how they believe preservation of Armenia’s physical survival and safety can best be achieved.

Aligning organizational stakeholders (i.e., diasporan leaders) and “sharing goals and information” are important to align objectives (Holman et al., 2007: p. 166). A combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods can be used to assess the concept of physical survival and safety (e.g., access to food, birth rates, emigration, and perceptions of harm (Carr, 1994). These research findings would assist Armenians in “uncovering and engaging people’s knowledge, wisdom, and heart to achieve strategic business results in their changing world” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 167). Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language (Carr, 1994). Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively gives meaning to their social reality. In contrast, quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzes numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest (Carr, 1994). The goals of quantitative research are to evaluate causal relationships between variables, make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Official statistics provide information on all major areas of citizens’ lives, such as economic and social development, living conditions, health, education, and the environment. These official (e.g., census) data collected by the Armenian government could be used to explore birth rates and emigration to better understand how the population in Armenia is changing. Similarly, a survey or questionnaire could capture data on the need for physical survival and safety and the perceived methods through which Armenia’s physical survival and safety could be pursued. Respondents in Armenia, for example, could be surveyed about access to proper food and shelter and perceived physical safety, while Armenians in the diaspora could be surveyed about prioritizing constructs related to physical survival and danger (i.e., food, water, shelter, and land). While surveying the Armenian diaspora would be challenging from a design perspective, this approach would be perceived as scientifically objective and would allow for testing and validating already constructed theories and hypotheses.

A contemporaneously administered qualitative design might offer a deeper understanding of the need for physical survival and safety. Coordinated Management of Meaning (CMM) holds that communication is a process that allows us to create and manage social reality (Rose, 2006). CMM describes how we, as natural communicators, make sense or create meaning of the world. CMM classifies interaction in two steps: first, by assigning meaning to what is happening in any given situation; and second, by acting based on the assigned meaning. Here, Armenian stakeholders would come together to identify a plan for Armenia’s physical survival and safety and what structural variables (i.e., the economy) can best assure this survival and safety. In contrast, Narrative research (Riessman, 1993) focuses on the lives of individuals as told through their own stories. The power of the narrative allows for an exploration of the meanings that participants derive from their experiences. Narrative research would involve, for example, listening to the children and families whose physical survival and safety are compromised by the military conflict in Artsakh and appreciating their humanitarian concerns.

4.2. Cultural Survival

A second primary need is the perpetuation of Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s respective cultural identities and heritages. Cultural identity is a part of a person’s identity, or their self-conception and self-perception, and is related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, social class, generation, locality, or any kind of social group that has its own distinct culture (Ennaji, 2005). In Armenia, the significance of culture is appreciated in its architecture, clothing, cuisine, language, and the performing and visual arts. In turn, Armenia’s diaspora perpetuates cultural identity through the establishment of Armenian churches, community centers, and schools; through the establishment of Armenian charities and civic organizations; by speaking, writing, and learning the Armenian language; by financially supporting political, humanitarian, and economic initiatives in Armenia proper; by engaging in political activities to benefit Armenia proper; and by providing assistance to vulnerable and marginalized populations in Armenia.

Historically, the Armenian diaspora has advocated for war and military intervention when conflict escalates despite grasping that military success will either be fleeting or impossible or appreciating the impact of conflict on children and families living in Armenia. Even when providing humanitarian assistance, the aide sometimes comes in the form of support for frontline personnel. It is important to make Armenians in the diaspora understand that financial support for active military hostilities may result in long-term harm to Armenia’s cultural identity, not perpetuate it, and may be inconsistent with what Armenians in Armenia need and desire.

The Collaborative Loops process “brings together dissimilar project teams … to develop their own strategies” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 114). This process involves the conflict disputants coming together to use their own experiences as the basis for change. Here, I consider the citizens of Armenia and Azerbaijan as actors who might come together, independent of their respective government and military actors, to discuss the impact the Artsakh war has had on their daily lives. It is vital that both states understand that the common denominator of the Artsakh War is not the intrinsic value of the land itself, but what the land symbolizes – the embodiment of their respective cultures. If citizens of both nations can agree that cultural survival is the long-term aim, then perhaps there can be a mutual understanding that military hostilities is not the best method through which this aim can be achieved.

It is equally important, however, that representatives from different Armenian groups devise a unified strategy for solving the Artsakh question. This would involve determining who to include as decisionmakers and allowing those participants to develop a “compelling purpose” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 92). This approach is based on the notion of “open systems theory,” which holds that systems have external interactions, such as information, energy, or material transfers into or out of the system boundary, and “adult learning theory,” which posits that adults learn through interactions and the exchange of ideas among others (Holman et al., 2017: p. 98). It is through these open dialogues that the Armenian diaspora may realize that a fight mentality is not the most appropriate strategy if a primary long-term goal is cultural survival.

Because members of the Armenian diaspora are influenced not only by their Armenian heritage but by the communities and cultures within which they reside, the Collaborative Loops process will engage them to identify a common denominator of cultural import. This process will narrow the gap between what Armenians in the diaspora expect to achieve with military actions and the short- and long-term impact war has on those families in Armenia. When death, loss of tangible property, and relinquishment of land are the inevitable outcomes of conflict, the more advisable approach should be to reassess priorities.

The diaspora may need to recognize that its “fight” mentality could be harmful, and that cultural survival does not necessarily require the retention of land. Cultural survival promotes the rights, voices, and visions of individual ethnic groups and allows them to chart their own futures. While land unquestionably provides the territory within which one’s culture can prosper unobstructed, there are other ways by which ethnic identity can be promoted, including the perpetuation of language, religion, cuisine, and the performing and visual arts. There may be a disjuncture between what Armenians in the diaspora perceive as beneficial for Armenia and what Armenians in Armenia and Artsakh perceive as beneficial for Armenia’s survival in the long-term. Bridging this gap and forging collaboration among Armenians, in and out of Armenia, will be a critical first step.

It is important to understand how all Armenians define cultural identity and how the preservation of one’s heritage is best achieved. The participants would create a Collaborative Loop using the four engagement principles: 1) widen the circle of involvement; 2) connect people to each other; 3) create communities for action; and 4) embrace democracy (Holman et al., 2007: p. 89). A combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods can be used to assess, first, the perception of cultural identity, and second, how cultural identity can be perpetuated (Carr, 1994). Quantitatively, a survey or questionnaire could capture data on the need for cultural survival and prioritize the cultural imports that global Armenians perceive as critical to their culture, including language, cuisine, the performing and visual arts, and religion. That is, respondents could be asked questions about what part of the Armenian culture is most important to them and how these cultural constructs can best be preserved to assure cultural survival.

In contrast, phenomenology helps understand the meaning of people’s experiences and is concerned with understanding social and psychological phenomena from the perspectives of the people involved (Farina, 2014). In a phenomenological study, a combination of methods (e.g., conducting interviews, reading documents, or visiting places) are used to understand the meaning participants place on the phenomenon being examined. You rely on the participants’ own perspectives to provide insight into their motivations. Here, the phenomenon is the importance Armenians place on culture and the central components of their unique heritage.

4.3. Reduction of Harm

The third need is the reduction of short- and long-term harms associated with the Artsakh War. Armenia has suffered significant harm from the Artsakh conflict, which has continued for more than 30 years. Aside from human casualties and the ever-present fear of destruction, the Armenian community has wasted the charitable resources offered those interested in “supporting” Armenia, which hinders the long-term, post-conflict development and restoration of Armenia. Recalibration is needed. The goal of Scenario Thinking is to “arrive at a deeper understanding of the world” in which a community operates and “to use that understanding to inform your strategy and improve your ability to make better decisions today and in the future” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 332). Scenario Thinking helps decisionmakers “order and frame” their thinking about the distant future, while providing them with the “tools and the confidence to take action soon” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 332). Here, the reflective thinking process would allow the Artsakh actors to contemplate what, if anything, can be achieved by continuing the conflict and why that long-term goal (e.g., obtaining or retaining land) is so vital. If the long-term implication for the Artsakh conflict is physical and/or cultural survival through the retention (Armenia) or accumulation (Azerbaijan) of land, then the disputants may consider other non-military strategies to perpetuate their unique cultures.

Scenario Thinking is important because, to date, the Armenian diaspora has continuously supported the War in Artsakh, both emotionally and financially. The notion of not supporting active hostilities is anathema to diasporan Armenians. Because scenarios are hypotheses, “they are created and used in sets of multiple stories … that capture a range of future possibilities: good and bad, expected and surprising” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 332). To be successful, the Armenian diaspora will need to recognize that its “fight” mentality may be harmful to Armenia’s long-term survival and that cultural survival does not necessarily require the accumulation of retention of land. By considering and reviewing all possible outcomes (i.e., scenarios), a more informed long-term outcome can be considered.

The goal of scenario thinking is “to arrive at a deeper understanding of the world in which your organization or community operates, and to use that understanding to inform your strategy and improve your ability to make better decisions today and in the future” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 332). There may be a disjuncture between what Armenians in the diaspora perceive as beneficial for Armenia proper and what Armenians in Armenia and Artsakh perceive as advantageous for Armenia’s survival in the long-term. Bridging this gap and forging collaboration among Armenians, in and out of Armenia, will be a critical first step. At its core, “scenario thinking helps communities and organizations order and frame their thinking about the longer-term future, while providing them with the tools and the confidence to take action soon” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 332). This planning will allow the diaspora to not only perceive the current reality in Artsakh but envision future economic, military, and political scenarios for Armenia.

A combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods can be used to assess how the Armenian diaspora perceives the situation in Artsakh and what the long-term aspirations are (e.g., cultural survival). Because the Armenian diaspora is diverse, “the introduction of multiple perspectives, diverse voices that will shed new light on your strategic challenge, helps you better understand your own assumptions about the future, as well as the assumptions of others” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 336). The findings would assist the Armenian diaspora in “uncovering and engaging people’s knowledge, wisdom, and heart to achieve strategic business results in their changing world” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 167).

CMM explains how individuals can be brought into a mutual understanding and move forward with a new co-creation of meaning (Rose, 2006). Here, Armenian stakeholders (trainers and facilitators) would identify the short- and long-term harms associated with the Artsakh War and prioritize those harms for future prevention. In addition, a case study is an intensive study about a person, group, or community in which the researcher examines complex phenomena in the natural setting (Bromley, 1986). Case studies have the ability to fully show the experience of the observer; can give an idea to a certain audience that the experiment or observation being done is indeed reliable; and illustrate that the creation or gathering of data can lead to making practical improvements. Case studies force the researcher to disregard the almost infinite count of unique circumstances surrounding any given situation and force imitation rather than inspiration. Here, case studies of children and families can explore the short- and long-term effects of the war to understand the impact the conflict has had within various units to the individual (e.g., a military widow), the family (e.g., children), and the community.

Intervention should begin with network-building among Armenians in advance of engaging the international community or peacebuilding with Azerbaijan. Given the considerable number of Armenians in the diaspora, these external actors, who are both individual (i.e., the diaspora) and organizational, wield considerable influence in Armenia. The primary challenge to this network is facilitating and maintaining communication that could help overcome the differences between and among diasporan members and the organizations to which they belong. If the ultimate long-term goal for Armenians, both in Armenia and across the diaspora, is cultural survival, the primary decisionmakers should devise alternatives methods to military hostilities. The Armenian national identity is essentially a cultural one. From the historical depths of its culture and the dispersion of its bearers, it has acquired a richness and diversity rarely achieved within a single national entity, while keeping many fundamental elements that ensure its unity.

The most attractive intervention strategy to assure physical or cultural survival is to propagate Armenia’s ethnic identity independent of the retention of Artsakh. Given the strength of the Armenian diaspora and the existence of Armenia’s ancestral homeland, the enhancement of Armenia’s cultural identity must involve their coalescence. To achieve this strategy, stakeholders must, first, recalibrate their expectations for Artsakh; second, consider what characteristics are most indicative of Armenia’s cultural identity; and third, collaborate in the perpetuation of Armenia’s cultural survival independent of the retention of Artsakh.

5. The Network

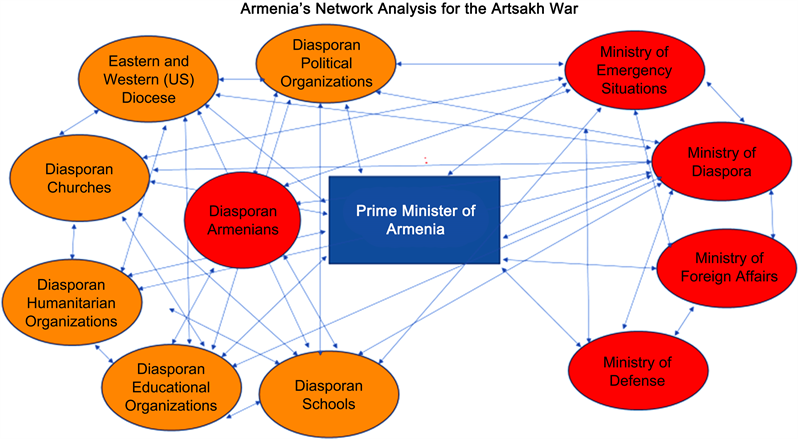

The network map presented below reflects the primary actors and relationships between the major Armenian stakeholders of the Artsakh War. The principle, singular actor of Armenia’s network, represented by the blue rectangle, is the Prime Minister of Armenia. The Prime Minister of Armenia is required by Armenia’s Constitution to set governmental policy and manage the activities of the government. The Prime Minister is the most powerful member of Armenian politics. Nikol Pashinyan, who assumed office in May 2018, is Armenia’s current Prime Minister.

The Government of Armenia is an executive council of government ministers. There are four principal Ministries that are represented by red ovals (to the right of the Prime Minister) in the Network Map. The Ministry of Defense implements policies in the defense sector. The Ministry of Emergency Situations implements a unified state policy on civil defense and population protection in emergency situations; develops and coordinates state regulation policies for displacement and sheltering processes and emergency and disaster response measures; ensures compliance with technical safety rules; and coordinates a system of disaster medicine and seismic risk reduction measures. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs implements Armenia’s foreign policy. The Ministry of Diaspora develops and implements policies to enhance the Armenia-Diaspora partnership. Its main objectives include repatriation and preserving promoting Armenia’s identity and culture through educational and cultural programs. As represented by the bi-directional arrows, the Ministries collaborate with each other and report to and advise the Prime Minister.

I have identified eight external (non-governmental) actors, represented by the orange ovals to the left of the Prime Minister, seven organizations and one collective group of individuals. Among the diasporan political organizations, the Armenian National Committee of American (ANCA) is the largest and most influential Armenian American grassroots political organization. Working in coordination with a network of offices, chapters and supporters throughout the United States, the ANCA actively advances the concerns of the Armenian American community on a broad range of issues, including Artsakh’s right to self-determination.

The Armenian identity is deeply connected with religion. Armenia was the first country to adopt Christianity as its state religion in 301 A.D., and as such, the Armenian Church as an institution is the common thread across the homeland and diaspora. While Armenians associate with different denominations of Christianity (e.g., Catholicism and Protestantism), they have an extraordinarily strong cultural connection to the Armenian Apostolic Church, to which nearly 97% of Armenians belong. The Eastern and Western Dioceses of the Armenian Apostolic Church are the spiritual homes of Armenians living in the Eastern and Western United States. Established in 1927, and headquartered in Burbank, California and New York, respectively, the mission is to lead the Armenian people to God by teaching the doctrines and traditions of the Armenian Church.

Diasporan humanitarian organizations protect the most vulnerable and marginalized populations in Armenia, a necessity for a second-world country plagued by poverty. For example, SOAR’s work has impacted thousands of children and adults with disabilities across a multitude of constructs, providing institutionalized children with the same educational, emotional, medical, and social support as their non-institutionalized counterparts. Represented by 143 Chapters and more than 600 volunteers worldwide, SOAR supports 34 orphanages, boarding schools, day centers, transitional centers, and orphan summer camps in four countries.

The Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) was established in Cairo in 1906. With the onset of the Second World War, headquarters relocated to New York City. With an annual international budget of more than $45 million, AGBU preserves and promotes the Armenian identity and heritage through educational and cultural programs. Today, the AGBU has chapters in 72 cities in 30 countries around the world, 27 cultural centers, and 24 schools throughout the US, Europe, Near East, South America, and Australia.

In 406 AD, clergyman Mesrob Mashtots created the original Armenian alphabet of 36 letters (two more were added later). Immediately after, the first Armenian schools opened. In the seventh century, Anania Shirakatsi developed a primary school that marked a milestone in Armenian education. Shirakatsi’s writings gained distinction outside of Armenia for pioneering ideas such as tailoring material according to age and emphasizing methods of teaching. Today, there are nearly 200 Armenian elementary and high schools around the world, primarily in the US, Canada, the Middle East, Europe, and Australia.

A “diaspora” is a scattered population whose origin lies in a separate geographic locale. Historically, the word diaspora referred to the mass dispersion of a population from its indigenous territories, specifically the dispersion of Jews. While the word was originally used to describe the forced displacement of certain peoples, “diasporas” is now generally used to describe those who identify with a homeland, like Armenia, but live outside of it (Harutyunyan, 2009). The most critical component of my network map, represented by the red circle, is the diaspora itself, the individual diasporan Armenians who collectively represent nearly 2/3 of the world’s Armenian population.14 The diaspora, one’s homecountry, and one’s host country seem to form a triadic relationship. The reflective approach to the three realities has wide individual and social implications. One’s own identity, as well as that of the group, is constantly being reconstructed in a dynamic process being fueled mainly by two antagonistic needs: adaptation and preservation (Hall, 1989). Reevaluations and omissions are common place so that the home land as stylized by diasporan Armenians is no longer congruent with the home land as perceived at home. Like identity, home is actively constituted through the experience of the diaspora (Axel, 2001: p. 11).

This triadic relationship between diasporan Armenians, their home country, and their host country is critical to understanding how the diaspora believes Armenian’s cultural and ethnic identity should be preserved. Because so many more Armenians live outside of Armenia than in Armenia proper, there is a belief that retaining land is the most important method by which to assure long-term cultural survival. When global conflict emerges, like in Artsakh, the reflexive response from Armenia’s diaspora is support for military engagement. The instinct to retain territory at all costs ultimately means that Armenians in the diaspora never consider the long-term ramifications of this intractable conflict as an obstacle to cultural survival.

The network structure is neither hierarchical nor decentralized. While final decisionmaking for military engagement rests with the Prime Minister, there is an interrelated relationship between the primary actors. This virtual network structure is an arrangement of otherwise independent organizations that come together to form an alliance to produce output and share core competencies. Each organization of the network focuses on its core competency and performs some portion of the activities necessary to deliver the desired outcome. Here, however, the primary actors almost certainly do not realize that they are part of a network. There is no collective strategic vision (i.e., there is no clearly defined vision that all members hope to achieve); there is no collaboration; there is no defined network leadership; there is virtually no communication among network actors; and there is little practicality (i.e., there is no clear understanding of what is needed and appropriate for the environment in which it operates.

A sustainability plan is a roadmap for achieving long-term goals and documenting strategies to continue successful programs, activities, and partnerships. At its core, however, any network presumes, first, that its actors know a network exists; second, concede that they are an integral part of this network; and third, commit to membership. Sustainability of the Artsakh network will be impossible unless and until the respective members agree that they are part of the network, commit to their inclusion in the network, and agree to collaborate and communicate.

6. Interventions and Challenges to Sustainability

Intervention for the Artsakh War should begin with network-building among Armenians. As noted by Kilduff and Tsai (2012: pp. 1-2), “the network of relationships within which we are embedded may have important consequences for the success or failure of our projects.” It would be important to explore cooperation among Armenian organizations to create a unified interventional front. These Armenian organizations reflect points on a network map that illustrate interrelationships and explore the “liability of unconnectedness,” or the inability for Armenians to connect to Armenians outside of their respective organizations (Kilduff & Tsai, 2012: p. 26). Armenian organizations with overlapping members (i.e., “multiplexity”) could facilitate information sharing (Linder, 2006: p. 12), because these individuals would be “bound to each other in different social arenas” (Kilduff & Tsai, 2012: p. 33).

Military and political decisionmaking, which could manifest in increased volatility or peacebuilding, rests with Armenia’s Prime Minister. His decisionmaking, however, is influenced by the organizations and people around him. This network map is disaggregated by two “sides” diasporan Armenians to the left and governmental entities in Armenia to the right. Given the considerable number of Armenians in the diaspora, these external actors, who are both individual (i.e., the diaspora) and organizational, wield considerable influence in Armenia. The primary challenge to this network is facilitating and maintaining communication that could help overcome the differences between and among the diasporan members and the organizations to which they belong. While the common denominator among diasporan members and organizations should be Armenia’s physical and cultural survival, their respective missions often divaricate and hybridize and are almost always hindered by fiscal competition. As a result, diasporan organizations often consider first their own continuity before collaborating toward the common goal of Armenia’s physical and cultural survival.

This network map reflects an international network of Armenians, most of whom are part of the global diaspora. In addition to being “Armenian,” they are members of unique groups which impact their willingness to collaborate. Engagement in Artsakh peacebuilding among members of the diaspora can be evaluated through either a quantitative approach (e.g., a survey) or a qualitative approach (e.g., case studies or ethnographic research). Ultimately, research will yield empirical data that can be used to determine the extent to which Armenians, within the diaspora and in Armenia proper, are committed to achieving and sustaining peace in Artsakh.

6.1. Strategies for Sustainability

If the ultimate long-term goal for Armenians, both in Armenia and in the diaspora, is cultural survival, the primary decisionmakers should devise alternatives methods to military hostilities. The Armenian national identity is a cultural one. The most attractive strategy to assure Armenia’s physical or cultural survival is to devise strategies for the propagation of ethnic identity independent of the retention of Artsakh. Given the strength of the Armenian diaspora and the existence of Armenia’s ancestral homeland, the enhancement of Armenia’s cultural identity must involve their coalescence. The more Armenia’s cultural identity can be enhanced and disseminated, the greater the likelihood of cultural survival. To achieve this strategy, the actors in the network map should, first, need to recalibrate their expectations for Artsakh; second, consider what characteristics are most indicative of Armenia’s cultural identity; and third, collaborate in the perpetuation of Armenia’s cultural survival independent of the retention of Artsakh.

6.2. Counterfactual

Counterfactual thinking is a concept in psychology that involves the human tendency to create possible alternatives to life events that have already occurred (i.e., something that is contrary to what actually happened). A counterfactual assertion is a conditional whose antecedent is false and whose consequent describes how the world would have been if the antecedent had obtained (Lewis, 1973). The counterfactual takes the form of a subjunctive conditional, for example, if the Armenian diaspora had not provided financial support from military engagements and frontline personnel, would the likelihood of Armenia’s cultural identify be enhanced. According to Weber (1996: p. 279), “the point of counterfactuals … is to facilitate creative thinking and open minds to plausibility.” The process of scenario building assumes that “most people … carry around with them an “official future,” a set of assumptions about what probably will be.” Suitable alternative scenarios through “counterfactualization” challenge these assumptions and offer potential alternatives that had not been previously contemplated.

Weber (1996) describes several steps for devising scenarios. The first step is “to identify a set of driving forces surrounding a problem, event or decision” (Weber, 1996: p. 279). Here, the driving forces include variables within Armenia’s control, like the potential galvanization of the diaspora toward peacebuilding and peace sustaining scenarios, and driving forces outside of Armenia’s control, including military aggression by Azerbaijan. The second step is to “identify predetermined elements in the story, things that are relatively certain” (Weber, 1996: p. 280). This might include, for example, identifying Artsakh’s rightful ownership and exploring to what extent the secondary actors in this conflict, like Russia and Turkey, are genuinely interested in building peace. The third step is “seeking out what is most uncertain and most important to making a particular decision or understanding a set of events” (Weber, 1996: p. 281). Here, Armenians might consider whether retaining the Artsakh territory itself is the most important goal or considering whether perpetuating Armenia’s cultural identity, independent of land retention, should be the long-term aim of the diaspora. Fourth, the plot line “describes how driving forces might plausibly behave as they interact with predetermined elements and different combinations of critical uncertainties” (Weber, 1996: p. 282). It would be important to consider the duration and intractability of the Artsakh War to best appreciate potential optimal solutions. Because scenario creation and action are closely related, Weber (1996: p. 284) suggests that “developing sets of implications that attach to different scenarios is a central part of the process.” Here, it would be important for the government of Armenia, the Armenian diaspora, and the residents of Artsakh to consider what Armenia’s long-term survival would be like if Artsakh were lost or relinquished.

6.3. Sustainable Change

Given the intractability of the conflict, it is important determine if peacebuilding change in Artsakh is sustainable. Holman et al. (2007) offer four characteristics to assess if a change is sustainable. First, direction is the mapping of a particular path, the evidence for which is legitimacy, the acknowledgment of inter-group beliefs, and flexibility (Holman et al., 2007: p. 60). Second, energy, or “the drive that people have to advance the change initiative” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 61), is evidenced by emotional engagement, collaboration, meaningful expression, and mutual respect. Third, distributed leadership, which “requires that people at all levels, in all locations, are authorized to own their own problems and solutions” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 62), is evidenced by a genuine commitment to advancement, demonstrable improvement, and mutual accountability. Fourth, the appropriate mobilization of resources, or how “time, people, money, and technology are mobilized and deployed to places they most benefit the organization or community” (Holman et al., 2007: p. 62), is evidenced by a focus on common ground and sustained communication.

How can we measure commitment to peacebuilding sustainability in Artsakh? My map reflects an international network of Armenians, most of whom are part of the global diaspora. In addition to being “Armenian,” they are members of unique groups which impact their willingness to collaborate. I can assess engagement in Artsakh peacebuilding among members of the diaspora through either a quantitative approach (e.g., a survey) or a qualitative approach (e.g., case studies or ethnographic research). Ultimately, the research process will yield empirical data that be used to determine the extent to which Armenians, within the diaspora and in Armenia proper, are committed to achieving and sustaining peace in Artsakh.

For the Artsakh War, sustainable change should manifest itself in peacebuilding. Fitzduff (2021) offers four important peacebuilding principles relevant to the Artsakh War. First, remember that anger and aggression often come from fear. According to Fitzduff (2021: p. 142), “fear is usually hidden behind anger,” so it is a better “to ask ourselves and others about what people/communities/nations are afraid of, rather than what just they are angry about.” Here, if a state’s physical and cultural survival could be assured, anger and violence to assure a state’s physical and cultural survival could be diminished.

Second, don’t bother (too much) with fact-checking. According to Fitzduff (2021: p. 143), it is important to “recognize that rational argument has its limits” and “to logically attack the opinions of someone who has a heartfelt belief that is socially shared with many others in their network is not often a useful strategy.” With respect to the Artsakh War, media accounts often detail how recent hostilities began or escalated (i.e., identifying who was the aggressor). While there are international laws that prohibit aggression and rules of law that should be followed, knowing with certainty which state may have been the aggressor at a single point in time seems meaningless for a conflict that has lasted for more than 30 years.

Third, we all divide the world into “us” and “them and we usually support “us.” According to Fitzduff (2021: p. 143), “people … have negative feelings toward other groups,” and these “personal and group feelings are often a remnant of our family, community, and national warning systems about those who are seen as “strangers.” This principle raises two critical issues: 1) our appreciation of negative feelings is sometimes a product of learned behavior and not firsthand experiences. For example, Armenians are taught that Turkey massacred 1.5 million Armenians in 1915 (i.e., the first genocide of the 20th century). This historical account is a part of every Armenian’s childhood learning. In contrast, Turkish youth, who were never taught about a genocide, are angered that their ancestors have been accused of perpetrating genocide. This “us v. them” principle is not a product of any direct interaction or negative experiences with modern-day Turks, but instead results from the educational and historical reality that has been passed on (or not passed on) through multiple generations; 2) “us v. them” is too simplistic a characterization given the existence of sub-groups. That is, while the idea of “us v. them” may create two opposing factions, what happens when the “us” is comprised of two different and sometimes competing factions (like Armenians in the diaspora against Armenians in Armenia)?

Fourth, and most importantly, remember to work with diasporas. According to Fitzduff (2021: p. 146), “because of the often-insecure nature of their membership of a national or regional group and the need to prove themselves loyal to a cause, diaspora communities are often the last to be open to the compromises necessary for peacebuilding.” As such, diasporan interventions often facilitate discord and inhibit peacebuilding. This principle is critical to understanding the Artsakh War. There may be a disjuncture between what Armenians in the diaspora perceive as beneficial for Armenia proper and what Armenians in Armenia and Artsakh perceive as advantageous for Armenia’s physical survival and safety. Armenians in the diaspora may be more concerned with the retention and preservation of land (Artsakh and Armenia proper), while Armenians in Armenia and Artsakh may be most concerned with access to food, clean water, and shelter. While all of these needs are related to physical survival and safety, prioritization may forge a deeper understanding of their interconnectedness. To facilitate peacebuilding, the Armenian diaspora will need to recognize that the physical survival and safety of Armenia is hindered by active military hostilities, particularly in a state whose economic and medical infrastructure may not be equipped to adequately address significant human casualties. Bridging this gap and devising collaboration among Armenians, in and out of Armenia, will be a critical first step. It is important to understand how all Armenians define physical survival and safety, how they prioritize the constructs associated with physical survival and safety, and how they believe preservation of Armenia’s physical survival and safety can best be achieved.

6.4. Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring is the systematic and routine collection of information from projects and programs for four main purposes: 1) to learn from experiences to improve practices and activities in the future; 2) to have internal and external accountability of the resources used and the results obtained; 3) to take informed decisions on the future of the initiative; and 4) to promote empowerment of beneficiaries of the initiative (World Bank Operations Evaluation Department, 2002). Evaluation is assessing, as systematically and objectively as possible, a completed project or program (or a phase of an ongoing project or program). Evaluations appraise data and information that inform strategic decisions, thus improving the project or program in the future (Rossi et al., 2018). Evaluations should help to draw conclusions about five main aspects of the intervention: relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact, and sustainability. The coalescence of monitoring and evaluation (M & E) is critical to every project or program and is understood as dialogue on development and its progress between all stakeholders. M & E helps improve project and organizational performance so that you can achieve the results you want. The monitoring piece of M & E provides detailed information on assessed activities and where improvements can be made. The evaluation side refers to the examination of a program to understand what has been achieved. A strong, thoughtful M & E plan is critical to the richness of your narrative.

Assuming that the diaspora is the critical starting point to the ultimate long-term goal of peace in Artsakh, there are multiple ways to monitor and evaluate the process and gauge sustainability. First, the actors included in the network map must acknowledge their involvement, recognize their importance, and commit to their inclusion in the network. If a first meeting were organized among network actors, for example, collective participation would be critical and provide a general understanding for commitment to the network itself. Second, collaboration, communication and meaningful dialogue among network members would signal a commitment to the network’s existence and to the long-term goal of peace in Artsakh. Third, there is a significant difference between Artsakh’s importance as a symbol of cultural identity and land that must be retained at all costs. Ashared understanding of what Artsakh represents and what peacebuilding involves would bond network actors such that real progress could be facilitated. Fourth, the network would need to develop a peacebuilding plan to ultimately share with Azerbaijan and the secondary and tertiary actors involved in the Artsakh War. While peace in Artsakh is achievable, it will be impossible to engage other actors unless and until Armenia and its diaspora can present a unified front on its intended goals and ambitions.

7. Conclusion

Diasporas are ethnic or cultural communities that cut across state boundaries and form transnational alliances and engage in transnational conflicts. The central focus of diasporas is their homeland state. The importance of a diasporan influence is no more evident than among Armenians, whose population is considerably larger globally than in Armenia proper. Of primary importance to Armenians, because of this geographic dispersion, is maintaining cultural values, beliefs, and aspirations. Whether peace can be achieved in Artsakh, however, depends primarily on the ability of diasporan Armenians to offer a unified strategy for maintaining Armenia’s cultural identity. Future research and policy efforts require communication and collaboration among ethnic and diasporan Armenians if permanent peace is to be achieved in Artsakh.

NOTES

1See Joshua Kucera, As Fighting Rages, What is Azerbaijan’s Goal? EurasiaNet (Sept. 29, 2020), https://eurasianet.org/as-fighting-rages-what-is-azerbaijans-goal (accessed April 7, 2022).

2See Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia Sign Artsakh Peace Deal, BBC News (Nov. 10, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54882564 (accessed April 7, 2022).

3U.N. Charter art. 1, para. 2.

4Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, A/RES/1514 (XV) (December 14, 1960).

5Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, A/RES/2625 (XXV) (October 24, 1970).

6Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (January 8, 1936).

7Id. at Art. 1.

8Id. at Art. 3.

9See https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54882564 (accessed April 7, 2022).

10Supra note 2.

11https://www.soar-us.org/.

12See https://www.adb.org/countries/armenia/poverty (accessed April 7, 2022).

13Id.

14See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armenian_diaspora (accessed April 7, 2022).