A Systematic Review of Perception of E-Learning Users in Formal Education during COVID-19 Pandemic ()

1. Introduction

E-Learning is a platform of education where it is done virtually and most of the time self-taught. The term “E-learning” was coined by Elliot Massie in his TechLearn Conference back in November 1999 which is defined as a professional term of online learning (Cross, 2004). There are other researchers who define E-learning as well. Bari et al. (2018) defined E-learning as a solution that allows the learners to fit learning according to their lifestyles and offers the ability to share material in all kinds of multimedia formats and documents. COVID19 pandemic has forced many institutes and organizations to carry out their training and education activities via E-learning (Alsharhan et al., 2021). Formal education is intentional, institutionalized and planned through private bodies and public organizations (UNESCO, n.d). According to the World Health Organization, on the 18th of May 2021, there have been 163,312,429 confirmed cases of the COVID-19 since 2019. All seven continents in the world reported the cases and education along with other sectors are badly affected. Thus, there is a need to examine the perception of E-learning users in formal education through studies from around the world. E-leaner users in this study refer to educators, students and those related to formal education all around the world. This systematic review inspected four aspects of perception of e-learning related to the pandemic situation. The aspects were challenges, impacts, and preferences of E-learning users in formal education. Their perceptions were also analyzed as to whether the studies show positive, negative, both or neutral perceptions of E-learning from the users.

2. Definition

2.1. E-Learning in Formal Education

E-learning places no stranger in the education system. In fact, schools around the world can be found equipped with electronics to promote the use of online learning in a formal education. The concept of E-learning is also understood in various views from a few individuals in their articles. Dhawan (2020) in his journal article entitled “Online Learning: A Panacea in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis” viewed e-learning as a tool that can make the teaching-learning more student centered, indicating that it is a tool that allows more flexibility in students’ study. E-learning consists of a pedagogical approach that aspires to be flexible, engaging and learner centered (Kaur et al., 2020). Teachers are to be aware of the freedom of experimenting with different approaches in teaching and learning as aid by the learning tools that allow e-learning. Teachers consequently would face challenges of preparing appropriate, informative and interesting lessons for their students (Kamarulzaman, Azman, Zahidi, & Yunus, 2021). Grading and commenting on students’ assignments or test online to keep track on the students’ progress can be done easily by the teacher (Yunus, Ang, & Hashim, 2021). In spite of that, some teachers would prefer the traditional classroom teaching and learning compared to dependent fully on e-learning. They believe that it cannot match the dynamic and interactive nature of face-to-face classroom instruction (Sreehari, 2020). Confronting students face-to-face is undeniably much more preferred in this case. Teachers were challenged in an unprecedented way to innovate learning (Clement & Yunus, 2021). This could also be due to the unpreparedness of both teachers and students of utilizing e-learning tools because of the sudden outbreak of the pandemic. Aboagye, Yawson, & Appiah (2020) found out in their study on the challenges faced by students of tertiary education during COVID-19 by inquiring perceptions of the students support the fact that their students are not ready for an online learning experience in this pandemic era. This proved that e-learning can mirror a negative notion to different groups of people in education. Nonetheless, there is no other way that students can receive education in this dire time of need. Either way, there is a need to find a balance to counter the existing problems. Priority should be about receiving ample educations by learners globally.

2.2. COVID-19 Impact on Education

COVID-19 was first detected in Wuhan, China in 2019 and since then has turmoiled the world into chaos for nearly two years. The first case detected outside China was in Thailand in 2020 (WHO, 2022) and not only it has spread internationally, but the virus also enhanced its mechanism and is getting harder to subdue. This has caused many changes in every country, affecting every division and sector whether it’s the industry, health and even education. Economy plummeted as each country enacts its own safety protocol and enforces citizens to limit their locomotion, thus decreasing productivity. COVID-19 leads to factory closures around the globe which lead to a contraction in macroeconomic supply of goods and services and moved the global economy into a stagflation (Maital & Barzani, 2020). Hospitals and shelters are full of COVID-19 patients and essential workers are burdened with heavy responsibilities despite the possibility of contracting the disease. In India, COVID-19 is going rampant claiming almost 304,000 lives on May 24th 2021 according to the JHU CSSE COVID-19 data. As in early June 2022, the death toll of COVID-19 has reached over 6 million (Worldometers, 2022). As the virus is still terrorizing the world, it is safer that most production are being procure safely at home. Everyone works from their homes and some countries only allow certain percentage of workers in offices to work while maintaining social distancing. World Health Organization generate advises that everyone should maintain a safe social distance from each other and encourage the usage of face masks. In some countries with dangerously high infestation of the virus, the government enacts lockdowns. This closely applies to the education systems all over the world. According to UNESCO (2021), over 1.5 billion students across 165 countries had been affected by school closures because of COVID-19 as in May of 2021. Students are left with no choice but to adopt learning from home via online learning as education is necessary in every possible way. During COVID-19 pandemic, ultimately online learning and teaching is necessary (Fabian, Xian, & Yunus, 2021).

3. Methodology

Literature review for this study is being done digitally as getting information through hardcopy is not possible at the moment amidst COVID-19 pandemic. This study instead relies on digital copies to obtain relating literature on the subject of e-learning during the virus outbreak. Systematic analysis is being used for this study by using databases such as SCORPUS and Google Scholar. This process has been done between the months of March of 2021 until June of 2021. The aim of this study is to provide insights of the perceptions of E-learning during COVID-19. This study uses the five phases proposed by Khan et al. (2003). Khan suggested using five phases when conducting a systematic literature review which are.

1) Framing questions for a review

2) Identifying relevant work

3) Assessing the quality of studies

4) Summarizing the evidence

5) Interpreting the findings

3.1. Phase 1: Framing Questions for a View

Filtering of the articles are done using the 5 phases of a proper systematic literature review introduced by Khan et al. (2003) where key words are focused on E-learning during COVID-19, and Formal education during COVID. The literatures chosen for this review were studies about online educations during COVID-19 whereby how it affected both educators and students. E-learning was translated as any technology terminology related to it, such as online learning, computer assist learning and ICT. The keywords for the search should be derived from the research questions (Xiao & Watson, 2019). The research questions are: 1) What are the perception of both educators and students about teaching and learning via E-learning in terms of challenges, impact, and students’ preferred way of learning? 2) What is their perceived acceptance of using E-learning in Formal education whether they are positive, negative or neutral? Below is a list of keywords to search articles related to the research questions in Table 1.

3.2. Phase 2: Identifying Relevant Work

In the phase 2, this review is to identify relevant work among the literatures that have been compiled. All of the literatures will be going under inclusion and exclusion whereby if any criteria are met, they are to be taken to be reviewed. The study selection criteria should flow directly from the review questions and be specified a priori (Khan et al., 2003). Therefore, all literatures pertaining keywords from the research questions are included. The literatures used were limited within two years from 2020 to 2021 as COVID-19 occurrence is very recent.

3.3. Phase 3: Assessing the Quality of the Studies

As a process of inclusion and exclusion, it was being done by filtering through some criteria that were chosen befitting to the study. Table 2 shows the inclusion criteria while Table 3 shows the exclusion criteria:

These criteria are important for a systematic literature review. There were 6 inclusion criteria and 6 exclusion criteria. The inclusions were created to cater for the lack of articles related to the review as COVID-19 related articles are relatively new. The inclusion criteria were crucial to answer the research questions in the study. On the other hand, exclusion criteria were just as important to filter articles that have connection to the study, but not as exclusive.

3.4. Phase 4: Summarizing the Evidence

The primary search engine used in the study was SCORPUS. The keywords were “E-learning during COVID-19” and “Perspective and perception of E-learning during COVID-19”. Synonym keywords for “E-learning” such as computer-assisted learning, digital learning, distant learning, online learning, remote online learning and virtual learning were also acceptable in the search for suitable articles. The articles searched were between the year 2020 and 2021. There were about 199 articles found under these keywords. 39 articles were omitted because they were not articles or full access articles, and about 135 articles were excluded as criteria were not met. Thus, only 33 articles were included from SCORPUS.

The second database used was Google Scholar. The keywords used are similar to the ones used in SCORPUS which were “E-learning during COVID-19” and “Perspective and perception of E-learning during COVID-19”. Synonym keywords for “E-learning” such as computer-assisted learning, digital learning, distant learning, online learning, remote online learning and virtual learning were also acceptable in the search for suitable articles. The articles searched were strictly between the year 2020 and 2021. There were about 111 articles found in the category. 13 articles however were omitted because they were not articles or full access articles. About 81 articles were omitted because they were irrelevant to the inclusive criteria. Finally, only 15 articles were used in this study after the filtering process. The search process is summarized in the following PRISMA flow chart as shown in Figure 1: PRISMA Flows Chart.

4. Results

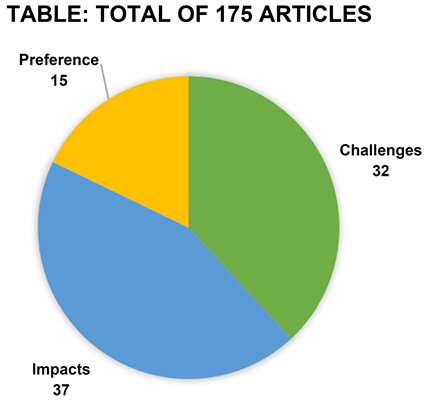

Phase 5 is to interpret the results by analyzing data using a content analysis. Categorical data is being used to reveal the trends. Articles from the two years starting from 2020 to 2021 were collected amounting to 310 articles but only 40 articles matched the criteria for inclusion. The table below shows the analysis of methodology from the articles chosen. As shown in Table 4, aspects of discussion of articles are categorized by what the study examined which were challenges, impacts, and preference of learning medium. The data is divided into three criteria which highlighted the challenges, impacts, and preferences of learning medium from the articles. Most articles that focusing on the perceptions of formal education during COVID-19 focus on these three criteria. The overall result can be seen in the pie chart in Chart 1.

![]()

Table 4. Authors, challenges, impacts and preference of learning medium list.

Chart 1. Challenges, impacts & preferences.

It should be noted that all samples from these studies are from any level of formal education that used E-learning. From the data above, impacts were the most discussed aspect in these studies followed by challenges and then preference. Impacts in the discussion of the articles chosen discussed both advantages and disadvantages of E-learning. On the other hand, the overall perceptions were varied as studies related found in their results. The results are categorized as shown in Table 5 and Chart 2.

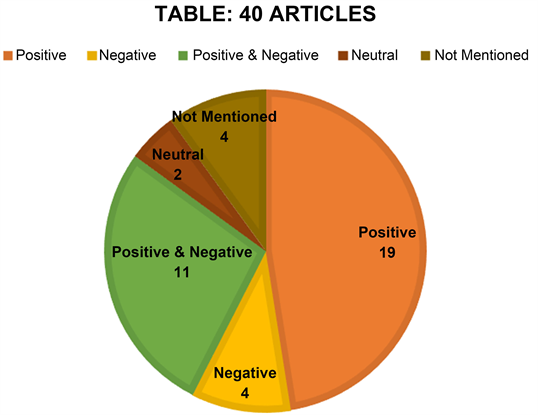

![]()

Table 5. Perceptions comparison list.

Chart 2. Perception comparison.

From Table 5 and Chart 2, most studies have positive perceptions in E-learning. The least perception is neutral whereby two studies discuss that E-learning did not provide any significant results.

5. Discussion

In this discussion, the perception of E-learning users in formal education during COVID-19 will be discussed in four separate aspects which are the challenges, impacts, learning preferences and the overall perceptions.

5.1. Challenges of Using E-Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic

A total of 32 articles out of 40 discussed the challenges faced when using E-learning during the virus outbreak. Most studies discuss the internet connectivity and availability as the most significant challenge [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Maican, & Cocoradă, 2021), (Ibrahim et al., 2021), (Babinčáková & Bernard, 2020), (Tuma et al., 2021), (Sreehari, 2020), (Gherheș et al., 2021), (Morgado et al., 2021), (Bhattarai et al., 2021), (Khafaga, 2021), (Mulyani et al., 2021), (Todri et al., 2020), (Afzal et al., 2020), (Famularsih, 2020), (Eltayeb et al., 2020), (Rahim & Chandran, 2021), (Rahman, 2020), (Ansari et al., 2021), (Ansari et al., 2021), (El-Sayed Ebaid, 2020), (Hazaymeh, 2021), (Allo, 2020), (Alkinani, 2021), (Alsarayreh, 2020)] when using E-learning during the COVID-19 outbreak for teaching and learning. Economic burden was also a reason for internet inaccessibility in some of the studies [ (Saripudin et al., 2020), (Alkinani, 2021)]. Practical learning in formal education was also challenging as it cannot be conducted properly through E-learning [ (Abbasi et al., 2020), (Ibrahim et al., 2021), (Morgado et al., 2021), (Khafaga, 2021)]. There were also lacked or limited student-teacher interaction discussed [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Park & Kim, 2020), (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021), (Ibrahim et al., 2021), (Razami & Ibrahim, 2021), (Bhattarai et al., 2021), (Eltayeb et al., 2020), (Hazaymeh, 2021), (Allo, 2020)] as well as lacked of peer interaction [ (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Morgado, et al., 2021), (Bhattarai et al., 2021), (Hazaymeh, 2021), (Allo, 2020)]. Some studies discovered that delivery of learning and teaching content via E-learning were inefficient and lacking [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Babinčáková & Bernard, 2020), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Ansari et al., 2021), (Todri et al., 2020), (Eltayeb et al., 2020), (Haleman & Yamat, 2021), (Alkinani, 2021), (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021), (Alsarayreh, 2020)]. Students were easily distracted [ (Patil et al., 2021), (Razami & Ibrahim, 2021), (Morgado et al., 2021), (Saripudin et al., 2020), (Haleman & Yamat, 2021), (Rahim & Chandran, 2021), (Alsarayreh, 2020)] and unmotivated [ (Razami, & Ibrahim, 2021)] when using E-learning. The duration of online class or lecture were founded can be too long [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Tuma et al., 2021)]. Lack of training or exposure to E-learning also posed as a challenge to E-learning users [ (Mulyani et al., 2021), (Famularsih, 2020)]. Credibility of examination online was also questionable in a study reviewed [ (Mulyani et al., 2021)].

5.2. Impacts of E-Learning during COVID-19 in Formal Education

Impacts of E-learning on the studies examined weighed differently in the sense that E-learning bore both positive and negative outcomes. Below are impacts discussed in two separate sections.

5.2.1. Positive Impacts

E-learning was found to be adaptable and effective during the COVID-19 [ (Ibrahim et al., 2021), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Gherheș et al., 2021), (Ramachandran & Kumar, 2021), (Saripudin et al., 2020), (Ansari et al., 2021), (Todri et al., 2020), (Afzal et al., 2020), (Eltayeb et al., 2020), (Haleman & Yamat, 2021), (Allo, 2020), (Alkinani, 2021), (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021), (Md Yunus, Ang, & Hashim, 2021)]. It is appreciated as a good or excellent alternative to traditional study as to maintain social distancing [ (Gherheș et al., 2021), (Almekhlafy, 2020), (Rahman, 2020)]. Aside from good learning materials or content [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Khan et al., 2021), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Ramachandran & Kumar, 2021), (Nihayati & Indriani, 2021)], E-learning users also experienced easy access to online sources [ (Khan et al., 2021), (Razami & Ibrahim, 2021), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Morgado et al., 2021), (Todri et al., 2020), (Rahman, 2020), (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021)]. They enjoyed E-learning and found it to be comfortable [ (Khan et al., 2021), (Sreehari, 2020), (Razami & Ibrahim, 2021), (Syofyan et al., 2020), (Rahim & Chandran, 2021)], engaging [ (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Bhattarai et al., 2021), (Todri et al., 2020), (Haleman & Yamat, 2021)], impactful or benefiting [ (Patil et al., 2021), (Rahim & Chandran, 2021)], motivating [ (Ramachandran & Kumar, 2021)] and efficient [ (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021), (Eltayeb et al., 2020)]. Studies on impacts of E-learning were also founded to be cost effective [ (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021)], satisfying [ (Syofyan et al., 2020)] and technical support was provided [ (Alsarayreh, 2020)]. The ability of educators in technicality also positively impacted the use of E-learning [ (Park & Kim, 2020), (Ibrahim et al., 2021), (Md Yunus, Ang, & Hashim, 2021)]. E-learning users found E-learning to be flexible and time saving [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Khan et al., 2021), (Md Yunus, Ang, & Hashim, 2021), (Babinčáková & Bernard, 2020), (Sreehari, 2020), (Razami & Ibrahim, 2021), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Morgado et al., 2021), (Syofyan et al., 2020), (Mulyani et al., 2021), (Todri et al., 2020), (Rasiah et al., 2020), (Sevy-Biloon, 2021), (Rahim & Chandran, 2021), (El-Sayed Ebaid, 2020), (Allo, 2020), (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021)]. They also experienced improved performance in formal education [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Ibrahimet al., 2021), (Famularsih, 2020), (Nihayati & Indriani, 2021), (Sevy-Biloon, 2021), (Aliyyah, et al., 2020)] and some gained confidence [ (Khan et al., 2021), (El-Sayed Ebaid, 2020)] when using E-learning.

5.2.2. Negative Impacts

Although a few, some studies found that E-learning contributes to negative impacts towards E-learning users. Some users felt overwhelmed [ (Tuma et al., 2021)], anxious [ (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021)] as well as unsatisfied [(Almekhlafy, 2020)] with the use of E-learning. Some studies also discussed concerned with mental health [ (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021), (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021)] and academic performance [ (Afzal et al., 2020)]. Students mostly in the studies did not like the individualized [ (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021)] or late [ (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021)] feedback by their educators.

5.3. Learning Preferences

In this systematic review, only about 15 articles mentioned the preferences chosen by E-learning users. Most studies preferred blended learning whereby E-learning compliment or aligned with the traditional way of teaching and learning [ (Ibrahim et al., 2021), (Sreehari, 2020), (Patil et al., 2021), (Razami & Ibrahim, 2021), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Gherheș et al., 2021), (Saripudin et al., 2020), (Khafaga, 2021)]. Second highest number of study preferred face-to-face study or teaching compared to using E-learning [ (Abbasi et al., 2020), (Khalil et al., 2020), (Babinčáková & Bernard, 2020), (Tuma et al., 2021), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Morgado et al., 2021), (Nihayati, & Indriani, 2021)]. Only about three studies preferred E-learning as a teaching and learning medium [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Syofyan et al., 2020), (Sevy-Biloon, 2021)].

5.4. Overall Perceptions of E-Learning Users in Formal Education during COVID-19 Pandemic

Overall, most studies showed positivity towards the use of E-learning in formal education during the pandemic. About 19 articles showed positive perceptions [ (Khalil et al., 2020), (Khan et al., 2021), (Park & Kim, 2020), (Sreehari, 2020), (Patil et al., 2021), (Gherheș et al., 2021), (Ramachandran & Kumar, 2021), (Bhattarai et al., 2021), (Saripudin et al., 2020), (Syofyan et al., 2020), (Mulyani et al., 2021), (Rasiah et al., 2020), (Afzal et al., 2020), (Eltayeb et al., 2020), (Sevy-Biloon, 2021), (Rahman, 2020), (Allo, 2020), (Alkinani, 2021), (Aliyyah et al., 2020)] and only 4 articles showed negative perceptions [ (Abbasi et al., 2020), (Khafaga, 2021), (Almekhlafy, 2020), (Hazaymeh, 2021)]. 11 articles showed both negative and positive perceptions present in their studies [ (Maican & Cocoradă, 2021), (Razami & Ibrahim, 2021), (Sawarkar, Sawarkar, & Kuchewar, 2020), (Morgado et al., 2021), (Todri et al., 2020), (Famularsih, 2020), (Nihayati & Indriani, 2021), (Haleman & Yamat, 2021), (Rahim & Chandran, 2021), (El-Sayed Ebaid, 2020), (Rahmt Allah & Mohamedahmed, 2021)] and 2 articles displayed a neutral perception [ (Alsarayreh, 2020), (Md Yunus, Ang, & Hashim, 2021)]. 4 articles did not display any stand on the overall perception [ (Ibrahim et al., 2021), (Babinčáková & Bernard, 2020), (Tuma et al., 2021), (Ansari et al., 2021)]. The overall perception of each study is mirrored mostly in the impacts discussed.

6. Conclusion

E-learning in the past was only as good as implemented in a blended learning, where technology provides aids to educators to teach in a traditional face-to-face classroom. After the outbreak of COVID-19, it became the quintessential tool as it became the domain platform of conveying education. Education system from across the world relies heavily on virtual learning as countries began to close schools and institution to curb the virus from spreading. Researchers on finding essential ways to implement online learning will prove to be useful in the future if similar situation is being imposed again. By then, readiness of students and educators should already be subpar with minimal consequences.

7. Challenges and Limitations

This study only covers the latest articles on the topic of perception of E-learning during COVID-19. As the topic is relatively new as it is related to the pandemic, articles were still insufficient to provide a defined perspective of E-learning users in general. Articles were also only obtained from two databases, SCORPUS and Google Scholar. There are possibilities of related articles that can be found through other databases such as ERIC or WoS. Due to limited resources, accessibility to articles related and time constraint, articles were only examined from the two databases. Other than that, articles also examined preferred medium of E-learning which were not covered due to time constraint and the focus of the study.

8. Implication and Recommendations

This systematic review has brought all kinds of perspectives of the use of E-learning worldwide due to the pandemic ordeal. From the study it is found that impact of COVID-19 on formal education around the globe is the most discussed topic among the selected research articles. The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak is perceived as positive in most of the articles on formal education. Further research on the feasibility and effectiveness should be done to further examine the intrinsic issues or problems regarding the use of E-learning in formal education. The perspectives obtained in this study also can be used to seek balance in the pedagogical aspect of the use of E-learning. Collaboration and innovation from essential parties such as government, teachers, parents, and schools were crucial to optimise the efficacy and practicality of e-learning during this critical period (Lukas & Yunus, 2021). Educators can reevaluate their approaches in E-learning to cater to the absence of needs as portrayed in the results. Researchers should use this opportunity to further study the specific needs of E-learning users.