Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Evidence of Countercyclical Macroeconomic Policies Implemented during the Subprime and COVID-19 Crises: The Brazilian Case ()

1. Introduction

As is well known, in the last years the world economy has faced two several economic crises: the first one was the 2007-2008 international financial crisis (IFC) that resulted in the 2009 Great Recession (GR); and, recently, 2020, the lockdown restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic initiated the largest economic recession in the history of world economy, after the Great Depression (1929-1933), involving both the financial and the real markets.

The effects of these crises were not neutral in economic and social terms, mainly because the crises have substantially altered the dynamic process of the international economy and have represented a major turning point. Governments of both the G7 countries and the emerging countries have responded to the IFC and the COVID-19 crisis with massive countercyclical fiscal and monetary policies.

In the Brazilian case, at the time of the IFC, the response of the Brazilian Economic Authorities (BEAs) was swift and involved important fiscal, monetary, credit, financial, and exchange rate policies, while in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic the BEAs’ measures, though not as swiftly, were based only on fiscal and monetary, mostly to provide liquidity and capital to the financial system, policies.

Given the above, the objective of this article is to analyze the countercyclical economic policies, specifically the fiscal and monetary policies, implemented by the BEAs in response to the IFC and the COVID-19 crisis, as well as to evaluate the impact of them on the Brazilian economy during periods of economic growth and economic crisis.

To achieve this aim, this article is divided into following sections. Section 2 briefly presents the Keynesian macroeconomic policies. Section 3 presents and analyses the countercyclical macroeconomic policies implemented in Brazil in both crises—the IFC and the COVID-19. Section 4 evaluates, empirically, the effects of fiscal and monetary policies in the Brazilian economy during the period 1996-2020, paying close attention to the impacts of these economic policies in situations of economic growth and economic crisis. The results are consistent with the idea that fiscal and monetary policies are able to affect the economic cycles, reversing the scenario of uncertainty, as was the case in the IFC and in the COVID-19. Thus, it corroborates the Keynes’ ideas, that is, countercyclical economic policies are important to expand the levels of economic growth and employment, mainly in times of economic crises.

2. Keynesian Macroeconomic Policies

In short, in the Keynesian theory investment is the key variable to determine the trajectory of the economic system. Entrepreneurs base their investment decision-making on expectations about real outcomes in the future. However, if the outcomes of these future prospects are uncertain, money is preferred to capital goods. Thus, if liquidity preference increases, there is a situation of insufficient effective demand which cools economic activity down, culminating in recession and unemployment.

To avoid this scenario, Keynes (2007: p. 379) states that, “the central controls necessary to [expand aggregate demand and] ensure full employment will, of course, involve a large extension of the traditional functions of the government”. The main component of these central controls is macroeconomic policies, since they act as an anchor to the entrepreneurs’ expectations. Thus, macroeconomic policy is the true “market signal” in Keynesian economics, serving as the basis upon which entrepreneurs can formulate well thought out expectations to make sound investment decisions. However, the success of the macroeconomic policies is not assured, considering the uncertainty that prevails.

As Keynes (1971: p. 35) warned, “even if such a policy were not wholly successful, either in counteracting expectations or in avoiding actual movements, it would be an improvement on the policy of sitting quietly.” Hence, Keynes (2007: p. 378) argued that, “a somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment.” According to Ferrari Filho and Conceição (2005), the idea of “socialization of investment” means that the State has to “create” an endogenous institutional mechanism to stimulate the economic agent’s decisions to consume and invest. In the same line, Marcuzzo (2010: p. 190) argues that Keynes proclaimed what needed to be done in order “to sustain the level of investment, but it should be interpreted more in the sense of ‘stabilizing business confidence’ than a plea for debt-financed public works”.

2.1. Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy has direct impact on aggregate demand—more specifically on consumption and investment—and constitutes the main instrument of State economic intervention. It is anchored in tax policy, on the one hand, and in public expenditures, on the other hand.

As Keynes (1972, 2007) pointed out, tax policy serves to increase available income, thus fostering expansion of effective demand, and it can also be used to improve income distribution. For instance, to moderate the gains of the rentiers in the financial and exchange rate markets, Keynes (1971: p. 55) argued that “capital levy must surely be preferred on grounds both of expediency and of justice”, as well as he suggested an inheritance tax because “a fiscal policy of heavy death duties has the effect of increasing the community’s propensity to consume” (Keynes, 2007: p. 373).

According to Keynes (1980), public expenditures are related to the funds necessary to maintain the basic services the State provides to its population, as well as the resources necessary to stabilize, automatically, the economic cycles. The public spending management has to be split into two budgets: the ordinary, or current, and the capital. In the first one, the resources have to be allocated to the basic services offer by the State, such as education, health and social security, whereas the latter accounts for expenditures regarded as automatically stabilizing economic cycles. Although Keynes (1980) believed in the importance of these ordinary expenditures in fostering effective demand, he also argued that the current budget should be in surplus or, at least, in equilibrium.

Given that, how does Keynesian countercyclical fiscal policy have to be operated? According to Keynes, regarding the capital budget operation, 1) it may run into deficit but, in general, the surpluses obtained on the current budget would have to finance it, 2) public investments cannot compete with private investments, but they should be complementary to them (Keynes, 1972), 3) these investments should be made by public or semi-public institutions and are normally related to social inversions, which “are [those] made by no one if the State does not make them” (Keynes, 1972: p. 291), and 4) fiscal policy cannot merely be an instrument of last resort. Thus, its main goal, as an automatic stabilizer, is to prevent fluctuations by means of a capital budget that finances a stable and on-going program of long-term investments.

Given the Keynes’ idea regarding the fiscal policy as an instrument of State intervention, Minsky (2008) argued that private investment deficiencies need to be balanced by public spending, called “Big Government”.

In summary, for Keynes, fiscal policy has a strong macroeconomic role to pursue economic growth and income distribution. It must be implemented over time to prevent both peaks and slumps, avoiding entrepreneurs’ lack of confidence.

2.2. Monetary Policy

For Keynes, monetary policy should be conducted by managing the base interest rate in the economy to promote economic growth as its ultimate objective, instantaneously bringing investment and employment levels under the central bank’s surveillance.

In addition to its objective, monetary policy has four additional goals. First, it aims at keeping inflation under control, mainly because inflation affects the economic agents’ expectations, as well as unleashes liquidity preference, all of which are likely to lead the economy to an insufficient effective demand. Second, according to Arestis and Sawyer (2013), it has to be focused on financial stability. Third, it supervises and controls the liquidity of the economic system. This means that monetary policy needs to avoid a shortage of liquidity, as well as prohibiting banks from creating money in excess. Moreover, when controlling liquidity, central banks act as lenders of last resort, preventing bankruptcy of financial institutions and its financial contagion risks. Fourth, monetary policy has to stabilize the exchange rate, mainly because exchange rate movements have a vast influence not only on expectations, but also on a firm’s financial and operational stances.

Given those multiple goals, two questions arise: What are the monetary policy instruments? What are the monetary policy channels?

Concerning the monetary policy instruments, the central bank’s base interest rate is the price at which the monetary authority supplies reserves to banks. This rate is the cornerstone of the financial system yield-curve. After establishing its interest rate, the central bank conducts its monetary policy in the money market to keep the rate at the announced level. To do so, monetary policy uses either the discount window or open market operations. The discount window is the supply of reserves that central banks provide to banks that become illiquid due to more withdrawals than deposits of resources. Open market operations make the central bank’s interest rate effective, in accordance with the intentions of monetary policy. They are performed by the purchases and sales of bonds undertaken by the central bank in the money market. By these means, monetary policy manages the supply and demand for money and administers the yield-curve.

Monetary policy has various transmission channels into effective demand and, consequently, economic growth and employment. These channels are portfolio, credit, wealth, exchange rate and expectations. The portfolio channel is the most important one for interest rate transmission, due to its direct impact on the investment opportunity cost. Following Keynes’ (2007: Chapter 17) asset pricing theory, this channel acts by virtue of how economic agents and banks allocate their portfolios, based on the assets’ expected return, cost of carrying it all, and liquidity. The second transmission channel is the credit channel, which produces its effects by means of how financial institutions set the interest rate they charge their customers, which is a mark-up over the central bank’s base interest rate. The third transmission mechanism is the wealth channel that relies on the impact that interest rate shifts have on the market price of financial assets and depends on the degree that households use this changed price to finance their consumption. The fourth transmission channel is the effect of interest rate changes through the exchange rate. In addition to the expected variation in the exchange rate level, the differential between domestic and foreign interest rates is the variable that external capital investments seek when deciding which assets to buy. Hence, modifications of the local interest rate in relation to world interest rates change capital flows and thereby the exchange rate, impacting conjointly the cost of inputs, foreign attractiveness of domestic production, and the financial position of firms with external liabilities. The last transmission channel is expectations. In relation to it, Keynes (2007: pp. 197-198) pointed out that it is “important to distinguish between the changes in the rate of interest which are due to changes in the supply of money […] and those which are primarily due to changes in expectation affecting the liquidity function itself”. If expectations are as stable as required for conducting monetary policy, the difference of judgments that economic agents have about the future interest rates would set their liquidity preference in different degrees, motivating them to negotiate debt contracts. Nevertheless, diversity of individual expectations only happens if the central bank is able to maintain a safe state of expectations in the economy as a whole. Otherwise, if the central bank fails in this attempt, conventions in the financial system would be disorganized, driving expectations towards a strong liquidity preference.

In view of these summarized ideas, according to Keynes, if the monetary authorities wish to expand the volume of capital, they should lower the base interest rate to stimulate productive investments. This would, as a result, keep the interest rate at levels compatible with eliminating capital scarcity, a scarcity which would result in “euthanasia of the rentier”, a class that is not remunerated for its “risk and exercise of skill and judgment”, but for “exploiting the scarcity value of capital” (Keynes, 2007: pp. 375-376).

To sum up, Minsky (2008) proposed that a permanent “Big Bank” must, on the one hand, regulate the activities of monetary and financial institutions and, on the other hand, at the first sign of loan defaults, act as lender of last resort.

3. The Brazilian Countercyclical Macroeconomic Policies during the IFC and the COVID-19 Crisis

This section presents and analyses the countercyclical macroeconomic policies adopted in Brazil, specifically the fiscal and monetary policies, implemented by the BEAs in response to the IFC, and the COVID-19 crisis.

3.1. The BEAs’ Response to the IFC

Between the last quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009 the Brazilian economy was sharply affected by the IFC. More specifically, GDP shrank by 4.5 percent. In this context, the Government responded to the contagion effect of the systemic crisis with a broad variety of countercyclical macroeconomic measures, whose objective was to mitigate this effect both on the Brazilian financial system and on economic activity. Accordingly, the Central Bank of Brazil (CBB) and the Ministry of Finance spearheaded the IFC response which involved important fiscal, monetary, credit, finance and exchange rate measures.

Because the first effects of the IFC were felt in the Brazilian financial system, it was the CBB that had to respond first. Therefore, the CBB eased monetary policy by lowering the policy rate target—the base interest rate, called Selic, was lowered by 5 percentage points, from 13.75% in December 2008 to 8.75% in September 2009—and by increasing liquidity in the interbank market.

Along with the measures of monetary policy by the CBB, the Brazilian government decided to use the three major federal public banks—Banco do Brasil (BB), Caixa Econômica Federal (CEF) and the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES)—to expand credit and to play a countercyclical role in a context of tightening credit conditions by private banks.

The countercyclical fiscal policy included the stimulus package adopted by the Ministry of Finance to mitigate the negative impact of the external crisis on economic activity and the labor market. The stimulus package, equivalent to 1.3 percent of Brazil’s GDP in 2009, was based on government spending, tax cuts—mainly on industrial products—and subsidies, especially to the agricultural sector.

Moreover, the Brazilian government decided to increase the public resources to 1) the Programa Bolsa Família—it was created in October 2003 and provides financial aid to poor Brazilian families; 2) the Programa de Aceleração do Crescimento—it was launched in 2007 and consists of a set of investments, public and private, in the infrastructure sectors; 3) the Programa Minha Casa, Minha Vida—government incentives and subsidies for housing construction targeted at low and middle-income families; and 4) the extension of unemployment insurance benefits.

As a result of these measures, at the end of 2009 the Brazilian GDP decreased only 0.1%, while Brazil’s economic recovery was strong in 2010—GDP increased 7.5%. In its turn, the unemployment rate trajectory was the following: it increased from 7.1% (2008) to 8.1% (2009), and in 2010 it dropped to 6.7%. Thus, the Brazilian economy showed remarkable resilience and became one of the less affected economies by the IFC.

3.2. The BEAs’ Response to the COVID-19 Crisis

At the beginning of 2020, the world economy faced a serious health problem with the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Unlike other crises, the COVID-19 pandemic represented a double adverse shock of both demand and supply, triggering an economic collapse in the world economy. On the demand side, in view of the uncertainty, the consumption and investment decisions were postponed, either due to the fear of economic conditions or due to restrictions on the movement of people imposed by local authorities. On the supply side, due to the partial lockdown measures that were adopted, since social distancing was advised by World Health Organization to be the most effective means of curbing the progress of the pandemic crisis, firms could not offer their goods and services and workers (formal, informal and self-employed) were unable to work. It was in this scenario that the world economy, which had not yet fully recovered from the IFC, and from the GR that followed, had a complete reversal of current expectations. According to data released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2021), the GDP of the world economy was expected to fall by 4.9% in 2020, with a −8.0% decline predicted for developed countries and a −3.0% in developing and emerging countries. For the Brazilian economy, the estimated drop was much more acute: −9.1% (IMF, 2020).

The responses to the pandemic were swift in developed countries. As occurred during the IFC, in the context of COVID-19, governments and central banks have implemented countercyclical policies to mitigate the recessive impact, with an emphasis on fiscal expansions that increased public deficits and domestic debts. This has been in addition to monetary policy, with which the central banks’ base interest rate has been reduced.

With regard to Brazil, first of all, it is important to mention that, on the eve of the pandemic, the country was in obvious stagnation. In fact, after the two-year recession of 2015-2016 that led to an accumulated drop of 7.0% of GDP, in the years between 2017 and 2019, the average annual growth rate was only 1.2%. With the pandemic crisis, the Brazilian economic situation became worsen: in 2020, the GDP fell 4.1% and, according to IBGE (2021a), there was a general worsening in labor market indicators, along with the heightened social vulnerability of a significant portion of the population.

Unlike in the IFC, in which the BEAs quickly implemented countercyclical economic policies to mitigate the impact of the crisis on the Brazilian economy, the Minister of the Economy, Paulo Guedes, believed that the liberal reforms and the “expansionary fiscal austerity”—that is, the idea that fiscal adjustment stimulates a sustainable economic growth in the long run—approach were the appropriate responses to tackle the COVID-19 crisis.

However, the National Congress and the Supreme Court of Justice forced the Bolsonaro government to change the course of economic policy in the short term. Thus, countercyclical fiscal and monetary policies were implemented in the beginning of March 2020.

Starting with actions in the area of fiscal policy, a first point to mention was the approval on May 7, 2020 of the Constitutional Amendment Project (PEC) of the “War Budget”, which authorized the CBB (2021) to buy national treasury bonds (NTB) and private bonds to cope with pandemic spending. Such approval was necessary because, in addition to the prohibition by law of the CBB to directly finance NTB, the country has also found itself since 2016, under the legal imposition of the so-called “spending cap” that determines the real freeze of public spending on primary expenditures, including health and education, for a period of 20 years (until 2036).

Given that, the fiscal measures were organized around five main axes: 1) social protection measures, 2) employment protection measures, 3) company relief measures, 4) health and sanitary measures to combat the pandemic, and 5) sub-national entity assistance (states and municipalities).

In terms of social protection, the main measure was the approval of financial aid in the amount of R$600.00 (approximately USD 110.00), which is about half the minimum monthly salary in Brazil. The aid, which was paid for five months to around 65 million beneficiaries, covered the unemployed, the self-employed, and those registered in social programs such as Bolsa Família.

The employment protection measures, in turn, were intended to reduce the costs of maintaining jobs, preventing further layoffs. In this regard, employers were allowed to reduce hours or temporarily suspend employment contracts, having the government counterpart pay part of the monthly salaries.

Among the measures to assist companies, the deferment or temporary exemption from the payment of taxes are noteworthy.

Regarding the measures to directly combat the pandemic, the federal government made transfers directly to the states responsible for confronting the pandemic, via Sistema Único de Saúde (Unified Health System), in addition to strengthening the budget allocations of some ministries, such as the Ministries of Health, Defense and Science, Technology and Innovation. It also zeroed import tax rates on some products for medical and hospital use.

Finally, on measures to assist sub-national entities, a project was approved for the negotiation of loans, the suspension of debt payments by the states to the federal government (estimated at R$65 billion or USD 12 billion), and a transfer of R$60 billion (about USD 11 billion) for actions to combat the pandemic.

In short, the total amount of all fiscal measures implemented represented 7.0% of the Brazilian GDP.

Moving on to the field of monetary policy, the main actions taken by the BEAs aimed at providing liquidity to the National Financial System, allowing the resources to reach the firms and consumers, to avoid the liquidity preference typical in periods of uncertainty like the current one.

The first aspect to be mentioned is the significant cut in the base interest rate, which reached its lowest historical level. As mentioned, the stagnation in the pre-pandemic scenario allowed for a relatively long cycle of reductions in the Selic that, after remaining 15 months at 6.5% p.a., started a steady downward trend, reaching 4.5% p.a. in December 2019. When the pandemic started, the pace of decline intensified and, after nine consecutive falls, reached the historic mark of 2.0% p.a. at the beginning of August 2020. This scenario was made possible both by the deflationary context and by the low growth that had already come from previous years.

Finally, in addition to cuts in the Selic rate, monetary policy measures were categorized into two groups: measures for the release of liquidity and for the release of capital. Included in the first group, for instance, the compulsory deposits of the financial institutions were reduced from 31.0% to 25.0% and then to 17.0%. In the field of capital provision, the reduction of the capital requirement for credit operations to small and medium-sized companies was allowed, in addition to the institution of a specific line of credit for financing the floating capital of micro, small and medium-sized companies.

The impact of these measures mitigated the Brazilian recession caused by the COVID-19 crisis: in 2020 the GDP dropped 4.1% (much lower of the IMF’s (2020) previous expectations). The unemployment rate, however, increased from 11.9% (2019) to 13.5% (2020).

4. An Empirical Analysis of the Effects of Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Times of Economic Growth and Economic Crisis

The purpose of this section is to analyze the effects of macroeconomic policies, in particular, fiscal and monetary policies, on the economy. The idea is to show how fiscal and monetary policies affect the economy, both in periods of economic growth and economic crisis.

The empirical analysis is based on the following articles: Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2017), Jordà and Taylor (2016) and Gorodnichenko (2014) show the effects of the possible non-linearity between economic performance and fiscal policy, while Artis et al. (2003) and Krolzig (2003) investigated the non-linearity on economic activity as a result of monetary policy.

The section estimates a Markov-Switching Vector Autoregressive (MS-VAR) model, which is generally used to capture the effects of fiscal and monetary policies on the economy. According to Krolzig (1996, 1997), the MS-VAR models emerged from two sources: VAR models are related to Sims (1990) and they are widely used to analyze macroeconomic variables; and MS models show how these variables affect the economic performance. Moreover, Krolzig (1997) created a simple notation that allows the identification of MS-VAR models according to the dependence (or not) of the parameters in face of the economic growth and economic crisis situations.

The innovation of using the MS-VAR model is that it 1) dispenses the need to analyze the series stationary and 2) captures the presence of structural breaks. This allows, on the one hand, to preserve the series in its natural state, and, on the other one, to endogenize the structural breaks of the model.

The MS-VAR is estimated in a context which all parameters dependent on the economic performance. Thus, it configures an MSIAH (m)-VAR (p) model. The estimation of this model is based on Expectation-Maximization (EM). In this regard, we chose to estimate a model in which the intercept, the parameters and the variance use to change. Without this flexibility, the model would become more restricted and difficult to estimate.

For a K set of time series variables,

, a VAR model captures the dynamic interactions between these variables (Enders, 2010). Its basic form with an order p (VAR (p)) can be represented as follows:

(1)

where Ais are matrices of coefficients (K × K) and

are the error terms, supposedly with zero mean and independent.

It is important to mention that main advantage to using VAR model is the fact that it allows the estimation with many parameters and it also does not impose restrictions on the shape of the impulse-response functions.

Moreover, the coefficients of the VAR models are not directly interpreted, since the existence of multicollinearity makes them, in most cases, not statistically significant. These allow to capture the dynamic effect of an exogenous shock on the model’s variables in a given time horizon. In addition, through this method it is possible to ascertain the time in which the effects of a shock on a given variable are dissipated and the intensity of the responses as a result of the shocks.

The empirical analysis is developed for the Brazilian economy, between 1996 and 2020 (quarterly data). The variables used in the econometric analysis are as follows: the effective Selic interest rate (annualized); P is the inflation measured by the consumer price index (IPCA); y is the GDP (seasonally adjusted and deflated); and G is the deflated government expenditures. The description of the variables and their sources are available in the Appendix TableA1. The order of the estimated VAR begins with the shock variables on macroeconomic policy, interest rates and government expenditures, followed by the GDP and inflation variables.

The estimated model uses variables in level with two lags, which guarantees robustness and avoids the problem of over parameterization. Regarding the use of variables in level, instead of using the results of unit root tests, Sims (1990) emphasizes that the series should not be differentiated if the purpose of the estimation is to understand the interrelationships between the variables, given that the differentiation process leads to the loss of such relationships.

Given that, it estimated the impacts of fiscal and monetary policies on the economy in periods of economic growth and economic crisis. Thus, the model is divided into two economic regimes. Regime 1 refers to moments of economic growth, measured by rises in GDP, while regime 2 represents moments of economic crisis, measured by falls in GDP.

The data are used to estimate and analyze an unrestricted MS-VAR model, with intercept, variance and parameters varying according to the economic regimes. Thus, an MS (2)-VAR (2) was estimated. The justification for the use of the MS-VAR model comes from the possible non-linearity in the parameters of the model, due to significant changes of these parameters in both periods of economic growth and economic crisis. The investigation of this hypothesis is performed by the LR Test, under the null hypothesis that the model is linear in its parameters, as shown in Table 1.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on research data.

As shown in Table 1, it is possible to reject the null hypothesis of linearity with a 99.0% confidence level in relation to the alternative hypothesis that the tested model is non-linear. This result corroborates the use of the MS-VAR methodology.

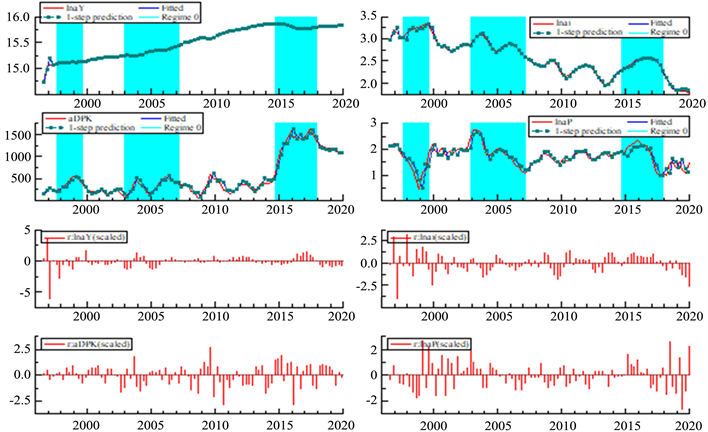

The convergence of the EM algorithm occurred after two interactions, with a probability of change of 0.0001. Figure 1 shows, based on the GDP variable, that is, Y, a good adjustment of the model in both situations of economic growth and economic crisis.

The MS (2)-VAR (2) model, estimated for the period 1996 to 2020, showed the following transition matrix of the economic situations:

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on research data.

Note: 1) Graphs 1, 2, 3 and 4 above represent, from left to right, respectively, GDP and interest rate policy; and 2) Graphs 5, 6, 7 and 8 (bottom) represent, from left to right, respectively, government expenditures and consumer price index.

Figure 1. Adjustment of the model.

In other words, according to the estimated model, once the economy is a situation of growth or crisis, the probability of staying in it is high. Thus, if the economy is increasing, the probability of switching to a situation of crisis is only 11.0%, while, to stay in it, the probability is 88.0%. The same occurs when the economy is a situation of crisis: once in it, the probability of change to a situation of economic growth is only 7.0%, while the probability of stay in the same situation is 93.0%.

In line with the estimated probabilities, the economic performances, growth and crisis, can be classified over time, as Table 2 shows.

![]()

Table 2. Classification of estimated economic performances.

Source: Author’s own elaboration from OxMetrics 7.2.

Note: Probabilities are between parentheses.

Regime 2 is more persistent, totaling 72 quarter of the analyzed period with an average duration of approximately 17 quarter. Regime 1 is less persistent, totaling 34 quarter of the analyzed period and having an average duration of 8.5 quarter.

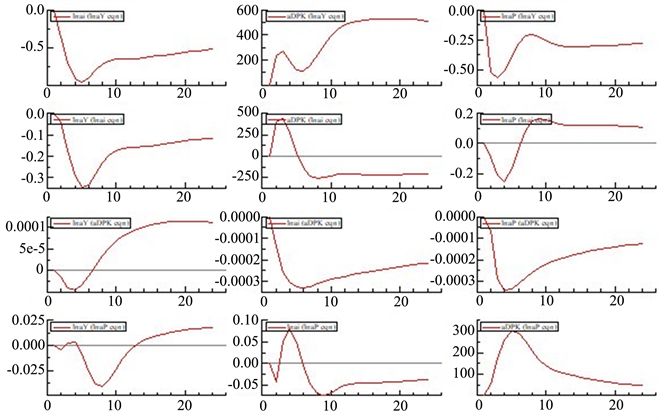

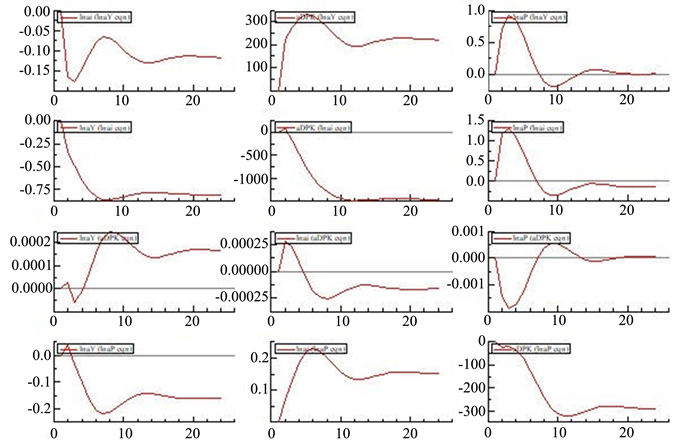

In order to further analyze the relationships between endogenous variables within the MS-VAR model, impulse-response functions are usually constructed. Figure 2 summarizes the results of the model in Regime 1 and Figure 3 summarizes the results for Regime 2.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 bring interesting results. The first column of Figure 2 summarizes the effects of the following variables on GDP: interest rates, government expenditures and prices. Specifically, the second and third graphs from top to bottom synthesize, respectively, the effects of monetary and fiscal policy on GDP.

Regarding the effects of monetary policy, represented by changes in the interest rate, it is worth noting that, initially, the responses of the variables refer to a positive impact in the interest rate. Therefore, an increase in the interest rate in regime 1, that is, in the economy’s growth situation (first column, second graph), implies a reduction in GDP that begins to dissipate from the sixth quarter onwards. In regime 2, a situation of economic crisis, an increase in the interest rate has a higher negative effect on GDP than in regime 1, as well as its effect does not dissipate quickly as occurred in regime 1.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on research data.

Note: 1) First line: Interest rate policy, government spending and inflation response to a GDP impact; 2) Second line: GDP, government spending and inflation response to an interest rate policy; 3) Third line: GDP, interest rate policy rate and inflation response to a government spending policy; and 4) Fourth line: GDP, interest rate policy rate and government spending response to an inflation shock.

Figure 2. Impulse-response function for Regime 1.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on research data.

Note: 1) First line: Interest rate policy, government spending and inflation response to a GDP impact; 2) Second line: GDP, government spending and inflation response to an interest rate policy; 3) Third line: GDP, interest rate policy rate and inflation response to a government spending policy; and 4) Fourth line: GDP, interest rate policy and government spending response to an inflation shock.

Figure 3. Impulse-response function for Regime 2.

As the effects of the economic impacts are symmetrical, we can conclude that the effects of an expansionary monetary policy, namely a reduction in the interest rate, in times of economic growth has a lesser effect than in times of economic crisis. Thus, it can be said that, during the analyzed period, the monetary stimulus has more important effects in times of economic crisis than in times of economic growth in Brazil.

In this subject, Libanio (2010) analysed the pro-cyclical and asymmetrical character of monetary policy under inflation targeting regime (ITR) in Brazil, evaluating how monetary policy has responded to fluctuations in output, especially in the downturn of the economic cycle. Initially, the author emphasizes that, ITRs, as is the case in Brazil, imply a strong emphasis on inflation stabilization, with low concerns for real effects on output and employment. The author’s results regarding the asymmetric behaviour of monetary policy showed that monetary policy has been pro-cyclical in “good” and “bad” times, but the estimated coefficients are higher and are only significant for “bad” times.

Concerning the effects of an expansionary fiscal policy on GDP, more specifically, of increases in government spending, the results of the impulse-response function in regime 1 (first column, third graph) show that the effects of an increase in government spending are lower in regime 1, when compared to regime 2. The important implication of this result is that the effects of fiscal policy on the Brazilian economy in the period observed tend to be greater in times of economic crisis (regime 2) than in moments economic growth (regime 1).

Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2017) also find that the effects of government spending depend on a country’s position in the business cycle. Expansionary fiscal policies adopted when the economy is weak stimulate output and reduce debt-to-GDP ratios. Differently, when the economy is strong the outcomes are more likely to have the conventional effects. According to the authors, their research is related to earlier studies, which find that government spending generate expansions and the government spending multiplier is larger when economy is weak than when economy is strong, such as: Blanchard and Perotti (2002), Ramey (2011), Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012, 2013) and Jordà and Taylor (2016).

The final conclusion that can be drawn from this empirical analysis is that fiscal and monetary stimuli are important for a weak economy, that is to say, one which is going through moments of economic crisis. The effects of monetary and fiscal policies on GDP are also positive in an economy with an economic growth situation; however, they are not as intense as in a weak economy.

Analyzing these results in the light of the recent trajectory of the Brazilian economy, the conclusion reached is that the country gave up important tools to stimulate its growth when it opted for the economic austerity agenda as a permanent policy of the State. In addition, the weak performance of fiscal and monetary policies in face of the current pandemic crisis may be one of the reasons for the extremely recessive impact observed here. It is worth mentioning that Brazil is probably among the countries that have lost the most in the context of the current COVID-19 crisis; both in terms of lives taken by the disease and in terms of the opportunity to resume a long-forgotten development agenda.

5. Final Remarks

The objective of this article was to analyze countercyclical economic policies, in particular, fiscal and monetary policies, implemented by the BEAs in response to the IFC and the current COVID-19 crisis. The effectiveness of both policies was analyzed in different contexts, under the assumption that such measures are even more important in times of economic crisis than in periods of economic growth.

To achieve its purpose, first it was outlined the Keynesian macroeconomic policies. Afterwards, it presented, analyzed and compared the policies implemented in Brazil in both crises, the IFC and the COVID-19, highlighting the different scenarios existing at the time of each crisis and the emphasis of the macroeconomic policies adopted at each time, as well as their results. Finally, the empirical part of the article assessed the effects of fiscal (government spending) and monetary (interest rate) policies on the Brazilian economy in the period 1996-2020, using an MS-VAR model.

It is important to mention that the Brazilian economic situations were completely different at the time when the two crises reached Brazil. In the first (the IFC), the country was growing and there was relative stability (inflation, interest rates, and public debt), while on the eve of the pandemic crisis, the context was one of obvious stagnation, with high unemployment and a high public deficit, a situation that the health crisis worsened. The actions of the BEAs were also different: during the IFC they acted quickly and effectively, focusing on transfer payments and investments in economic and social infrastructure; and, in the pandemic crisis, however, the BEAs’ action was slow and inconsistent, in such a way that fundamental policies were no longer implemented. This contributed to the advance of the health crisis and the worsening of the economic scenario.

Finally, in the empirical part of the article, it was observed that the effects of fiscal and monetary policies, from 1996 to 2020, proved to be more pronounced in the recessive context than in a situation of economic growth. This is in line with the Minsky (2008)’s idea that the economic system needs central authorities—“Big Government” and “Big Bank”—to act effectively to drive economic agents’ expectations in a scenario of increased uncertainty.

Appendix

![]()

Table A1. Description of variables used in estimations.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.