The Origins and Evolution of Anglo-Kenyan Military Diplomatic Relations Since 1963 ()

1. Introduction

During most of history, the use of military force was regarded as a craft or an art [1]. The history of military professionalism from the 18th century onwards is, thus, also the history of the development and growth of military education. Today, the military profession is not a particularly intellectual one, but it cannot afford to be anti-intellectual either. This study was inspired by the general concern that while the British military was branded an enemy military during Kenya’s pre-independence and decolonization period and viewed with hostility during the independence struggle, Kenya’s post-independence political dispensation continues to sustain these relations. Britain also continues to pursue these relations relentlessly to date. Currently, in Kenya, there has been a greater Kenyan public and academic interest especially in defence and national security issues and this has brought into attention the continuous long-term stationing of the British military in Kenya as an armed foreign force in peacetime [2]. These observations lead the researcher to trace the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963 when Kenya got her independence.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

Anglo-Kenyan Military Diplomatic Relation is one of the enduring colonial legacies within Kenya’s independence period and political dispensation. While the independence period has witnessed cordial diplomatic, trade and economic relations between the two countries, the ideal military professionalism is a key factor in interstate diplomatic relations. Anglo-Kenyan diplomatic relation has been beset with challenges embedded in military professionalism on both sides. These include challenges in professional training, academic training and character development in terms of military relations. This study, therefore, sought to trace the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963 when Kenya got her independence.

1.2. Objective of the Study

To trace the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations.

1.3. Research Question

In what ways have Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations evolved since 1963?

1.4. Justification of the Study

Weak military professionalism in Africa is regularly evident in news accounts of instability on the continent. Militaries collapsing in the face of attacks by irregular forces, coups, mutinies, looting, human rights abuses against civilian populations, corruption, and engagement in illicit trafficking activities are widespread. This pattern persists decades after the end of colonialism, despite billions of dollars of security sector assistance and longstanding rhetoric on the need to strengthen civil-military relations on the continent. The costs for not having established strong professional militaries are high. They give rise to persistent instability, chronic poverty, deterred investment, and stunted democratization. Breaking this vested interest that undermines efforts to build military professionalism in Kenya will require more than capacity building. It will need a sustained initiative that addresses the fundamental training disincentives to reform and establish constructive international military Diplomatic relations [3].

1.4.1. Academic Justification

Most of literature reviews are America centric and Eurocentric. On Anglo-Kenyan diplomatic relations, the literature deals with colonization and Kenya’s independence but scanty on the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations. This study will also inform the sub-discipline of international security studies and, therefore, provide a foundation for further research in the field of security studies. The findings of the study will improve the academics in Militaries relations and beyond by increasing reference materials in the libraries and academic institutions. Since Studies on military Diplomatic relations are scanty, this study was appropriate for students at all levels who are interested in peace and conflict studies, political science and diplomacy and international relations.

1.4.2. Policy Justification

This study is valuable towards policy formulation on origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963. Moreover, the study is useful to British and Kenya Governments in implementing proactive measures in addressing imbedded challenges of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations. This study will therefore, help to make policy suggestions to statist, non-statist actors and academic institutions and will assist in making recommendations pertaining to the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963.

2. Historical Evolution of Anglo-Kenyan Diplomatic Military Relations

The origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations can be traced back to the British colonial control of Kenya, which began with the Scramble for Africa in 1884-1885. This was followed by the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 that set the rules of colonial occupation and thereafter the partitioning of Africa into various spheres of influence [4].

Amidst the geo-political disputes notable was the 1890 Anglo-German Agreement better known as the Heligoland-Zanzibar treaty that settled most, if not all, of the complex colonial issues that arose from the ambitions of Great Britain and Germany in Africa. While the apparent goal of the treaty signed in 1890 was the exchange of Helgoland for Zanzibar, the principal motivation was the settlement of Anglo-German colonial boundaries and disputes in Africa, especially in East Africa.

These two small islands of Zanzibar and Heligoland (also known as Heligoland) the former located off the coast of modern-day Tanzania and the latter off the coast of Germany in the North Sea, were strategically included in this accord and had a large role in other inter-European territorial arrangements [5].

The outcome was that Britain would control the North, including Uganda and Germany would control the South. This agreement was formalized and Kenya was now under British authority. Profoundly, the Berlin conference was instrumental in not only erecting artificial boundaries around present day Kenya, but also in wresting diplomatic initiative from Kenyan people. In 1894 and 1895, Britain declared protectorate over Uganda and Kenya, respectively. Kenya’s boundaries were demarcated without the consultation of Kenya’s people. It can be deduced that the colonial boundaries led to the establishment of a large territorial entity that arbitrarily brought together over forty previously independent communities into one territorial entity. Even though Ogot and Ochieng study was useful to this study, it did not look at the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

The colonial state, and later the post-colonial state as argued by Ogot, would find it a daunting task wielding these communities into one nation-state. The Berlin Conference divided Africa into spheres of influence mainly amongst the major European imperial powers of Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, and Portugal, with each of the powers adopting its own strategies of administering the acquired spheres of influence. This step marked the onset of British colonialism and imperialism in the African continent and became known as the Scramble for Africa [6]. For Kenya, British interests became well-defined when the Imperial British East African Company (IBEAC) was granted a royal charter in 1888 and the subsequent declaration of the East African protectorate in 1895 so as to forestall the advent of other European powers in the region and to delimit the Sultan of Zanzibar dominion on the mainland [7].

Worth noting is the fact that the political, economic and geo-strategic considerations of the East Coast of Africa had attracted the attention of other major colonial powers beside Britain and Germany all of whom had laid claim to the East Coast of Africa. The East African Protectorate, which replaced the Imperial British East Africa Company, was created in 1895 and comprised present-day Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika (Tanganyika was colonized by the Germans and became a British protectorate after World War I and later became modern day Tanzania in 1964) [8]. Okoth study was useful to this study, but it is not specific to the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

The notion of Kenya as a colonial state began with the arrival of the British military in 1895. It is imperative to note here that the driving force for the European powers to claim part of East Africa was driven largely by among other reasons, the prestige of possessing a colony outside Europe, resettlement of surplus populations, the search for raw materials and new markets as well as the desire to spread Christianity and control of the source for river Nile [9]. The review of Matson was useful to this study, because it gave the reasons for British interest in Kenya but lacks the aspect of the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

The source of the Nile River was especially important to the British strategic defence. They believed that whoever controlled the source of the river Nile controlled North Africa and Egypt, and therefore, the Suez Canal and the trade routes to India and Asia [10]. It is worth noting that all the Kenyan nationalities resisted British control by waging struggles on many fronts; For example, forces under Waiyaki wa Hinga attacked and burnt the British station in Dagoretti in 1890, the Nandi resistance (the most tenacious of all) led by Koitalel arap Samoei of 1890, the Bukusu resistance of 1896, Giriama resistance of 1900,Gusii resistance of 1907 remain hallmarks of the African initial resistances to colonial rule and all of which formed the initial aggressive acts to the British in Kenya.

As a result, they became the causes of the first military expeditions and have been explored in depth by scholars like Bantley. This East African protectorate was under a territorial force called the Kings African Rifles (KAR), whose sole mandate was to protect and secure both the economic and strategic interests pioneered by the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC). The Portuguese had succeeded in gaining control of much of the Kenyan coast as evident by the vestiges left behind by the Portuguese like the Fort Jesus built in 1593 and the pillar of Vasco da Gama in Malindi. The Portuguese interests in Kenya and East Africa were centred mainly on controlling trade routes to India [11].

Kenya’s strategic location in East Africa and its valuable point of entry into the Horn of Africa had considerably given it more leverage amongst the other East African nations from the onset of colonial control and this fact had featured well in the British interests in the East Coast of Africa. This corroborated by Juma & Odhiamb [12] in their article “Geo-Political factors Influencing Kenya and Tanzania Foreign Policy Behaviour Since 1967” whey they wrote that:

… The fundamental geopolitical factors that have been central in shaping Kenya’s foreign policy posture since independence are: the Indian Ocean and the struggle of the big powers; Kenya’s location near the volatile and strategic Horn of Africa; the Nile River basin and Egypt’s ambitions; great powers struggle for resources and influence in Africa; war on terror; instability in the Great Lakes region; and discovery of fossil fuels in East Africa.

Kenya’s colonial history was unique because Britain’s colonial policy towards Kenya was long-term geared towards resettling a large number of white settler community and making Kenya a white man’s country. The Imperial British East Africa Company, the main commercial administrator of British East Africa, begun the construction of the Kenya-Uganda railway at the Kilindini Harbour in Mombasa in 1895 and around 1900, the rail line arrived at the city of Nairobi and around 1901 it arrived at Port Florence (current day Kisumu city) [13]. The review of Maxon work shows Kenya’s strategic location in East Africa but is scanty on the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

With the success of the Railway line, the first white settlers began arriving in Kenya as early as 1902. Under the Crown Land Ordinance of 1902 the sale and leasing of land to settlers began [14]. This ordinance underlined that the crown had original title to the land, and deserted or vacated land reverted back to the crown. Kenya was declared a white man’s crown colony in 1920 and in light of this development, two parallel dual economies mainly native economy and settler economy on the other hand were established [15].

Subsequently, the colonial state saw the need to alienate Africans from their land for colonial settlements in the Kenyan highlands dubbed the “White Highlands” where these white settlers were to occupy and embark on large scale plantation farming to sustain themselves and their economy. Gradually as Leys observes, the colonial state established itself through several sets of legislations most of which aimed at protecting the interests of the state officials and those of the white settler farmers [16].

Notable was the Kenya (Annexation) Order-in-Council, 1920 and the Kenya Colony Order-in-Council, 1921 that vested all arable land in the British Crown and totally disinherited indigenous Kenyans of their land according to Dilley. These legislations created the reserves for “natives” and located them away from areas scheduled for European settlement and this gave way for the colonial state first to control and to suppress the envisaged competition from the native African and Asian economies according to Leys.

Punitive legislations and taxation laws banning the Africans from cash crop farming were introduced by the colonial authority which forced the Africans to work in the settler farms after they were forcefully evicted from their farms and pushed to reserves where land ownership was not encouraged. The Crown Lands (Amendment) Ordinance, of 1938 gave legal effect to this dual policy of European “White Highlands” (or high potential areas) and African “Native Reserves” (or marginal lands) Okoth-Ogendo.

Within the international system and right at the same time, the Second World War (1939?45) broke out, and Kenya being an ally of Britain became an important British military base for successful campaigns against Italy in the Italian Somali land and Ethiopia. The same British military had conscripted Kenyans to serve their interests during the First World War and the Second World War. This fact is highlighted by Shiroya’s study on the role of African soldiers in World War II when he argues that the African participation posited African soldiers to politically galvanize against colonial rule as a result of their wartime experiences [17].

During the immediate pre-independence period, Anglo-Kenyan military diplomatic relations were geared towards colonial policing, with initial co-operation between the British military forces consisting of the First Lancashire fusiliers (from the Canal Zone) as well as the African troops known as the Kings African Rifles. The British troops would be primarily in charge of law enforcements in the white highlands while the KAR troops would patrol and engage Mau Mau in trouble spot areas [18]. Wunyabari study gives a detailed narrative of the war between the British troops and Mau Mau but lacks the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

2.1. Kenya’s Foreign Policy

Kenya’s long struggle for national liberation from colonialism set a strong foundation for its foreign policy orientation. The architects of the Republic of Kenya underscored the inextricable link between national independence and humanity’s larger freedom, equity and the inalienable right to a shared heritage. Kenya assumed its place as a sovereign state and actor in international relations upon independence in December 1963. Kenya’s Foreign Policy of November, 2014 has four chapters, its chapter two has pillars of Kenya’s Foreign Policy which are: Peace Diplomacy Pillar; Economic Diplomacy Pillar; Diplomacy Pillar; Environmental Diplomacy Pillar and Cultural Diplomacy Pillar [19].

The benchmarks guiding the country’s relations with the world were set by the imperative to re-align its goals at the international level to the turbulent and shifting dynamics of a divided world during the Cold War era (1945-1989). Even though Kenya’s liberation struggle enhanced the country’s international image and stature, paradoxically, this heroic history also risked playing into the East-West ideological divide. In order to strategically place the country in the international arena, the architects of Kenya’s foreign policy charted a pragmatic approach, informed by several principles, which have stood the test of time. This approach has ensured that Kenya successfully forges mutually beneficial alliances with the West while constructively engaging the East through its policy of positive economic and political non-alignment. Underlying Kenya’s peace and security diplomacy is the recognition of peace and stability as necessary pre-conditions for development and prosperity. Linked to this, is Kenya’s conviction that its own stability and economic wellbeing are dependent on the stability of the sub-region, Africa and the rest of the world [20].

Olewe [21] argues that for anyone to understand military interactions between Kenya and the major powers, it is important to know its sources of economic aid and technical assistance, since they are significant because of the great value Kenya has put on economic development, and therefore, one would expect Kenya’s trade and military interactions to be consistent with the major sources of its economic aid. According to Olewe, Kenya-Britain trading had significantly revealed that 75% of Kenya’s arms trade is with Britain, with Kenya holding a considerable percentage of British investments in the East African region. The work of Olewe looked at the military interactions between Kenya and the major powers but was not specific on the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

2.2. The Anglo-Kenyan Military Diplomatic Relations

The view that the idea of sovereignty in international relations theory is increasingly being subjected to unprecedented challenges by forces of globalization. One can as well talk of imperial globalization in reference to globalizations direct subordination of territories that proffer a regime of global surveillance.

Shiroya reveals in his study that the Second World War in 1940’s affected Africa-European relationship in more than one way and more so militarily. Kenya he notes contributed significantly (although many of them were conscripted to join the British military and more so the Kings African Rifles) into the British Army recruitment in the East Africa region and a significant number of Kenyan African soldiers fought alongside British soldiers in the British Army’s 21 brigade for the freedom of Britain. Shiroya’s study is relevant to this study as it laid foundation and also forms part of the colonial legacy in the present Kenya-British military diplomatic relations. As a stark reminder of this legacy, each year the British government and more so the British High Commissioner joins other Kenyans and Commonwealth countries representatives and veterans in remembrance day to commemorate the ex-world war soldiers who died in the struggle outside the war cemetery in Nairobi. However it does not highlight or touch on the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

True to it, on gaining independence the moderate Kenyatta’s government agreed to the willing buyer willing seller system of transferring land from the white settlers to Kenyan farmers. The British ensured that they armed the Kenyatta state hence future threats to Kenya’s stability could be dealt with by largely political means. According to Ley’s study helps explain Britain’s reasons for close involvement in defense matters in Kenya from independence. It meant that Britain enjoyed a large degree of continuity which this study sought to highlight by focusing on the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, the gap which this study has filled.

2.3. Decolonization of Kenya

Catalysed by the British determination to quell their fear of the spread of communism as an ideology in Kenya and the East African region, Kenya’s decolonization experience took a rather violent path. Having been formed in the early 1940s, Mau Mau has been cited as the biggest security threat to Britain’s colonial control of Kenya, especially the uprising’s culture of violence which had not only rationalized its actions but those of the British [22]. First, the clamor by Africans for return of alienated land by the British and freedom from British cruelty mainly associated with the white settlers, colonial chiefs and home guards, all triggered widespread resistance that saw the birth of the Mau Mau national liberation movement.

The British military training in Kenya evokes vivid memories of the Mau Mau war and the state of emergency. Viewed by many in Kenya as an imperialist power that was antithetical to the progression of Mau Mau Nationalism and whose influence had to be removed, their long-term stationing indeed evokes the question of whether Kenya gained independence or is still under Britain sovereignty. Mau Mau freedom fighters having fought the colonialists in order for Kenya to attain self-rule and the frequent return of the British soldiers at Archer’s Post, area for training since the Mau Mau war have left many perturbed according to Kanyinga.

Nissimi [23] notes that a military base in Kenya seemed to offer the ideal linchpin of Great Britain’s post-war strategic realignment to meet the challenges of a bipolar world. For them a military base known as “Templar barracks” had been for some years under construction at Kahawa, Kenya and the same had been identified as the most suitable location for a theatre reserve after the Suez Canal’s Aden base had been denied to them in rather dramatic circumstances. The outcome of the Suez crisis of 1956 and the strategic reemphasis on conventional warfare restored Kenya to the strategic map of the British defense planners and the subsequent world politics.

The fears that Kenya was bound to establish a socialist system after independence were unsettling to Britain and its Western allies. Considerably the Mau Mau liberation movement helped resurrect the idea of the military base although the rationale had changed. While the military base would simultaneously protect the British settlers and strengthen the anti-communist crusade, the latter introduced the Cold War component of Britain’s defence strategy beyond Kenya’s independence and significantly shaped the independence Kenyan politics and Britain’s unswerving loyalty to realism. This came to play constantly as it sought to follow realist principles by installing post-colonial regimes that were well disposed to the interests of the West [24].

2.4. The Kenyatta Era, 1963-1978

Kenya attained its independence in 1963 taking rights, privileges and obligation, in the international political system under international law and inherited its system of governance from the colonial authorities. In the build up to Kenya’s in dependence, three constitutional conferences were held in Lancaster House, London in the years 1960, 1962 and 1963 to facilitate the process of granting independence and self rule to Kenya by the British. There were three main interests the British wanted to safeguard during these negotiations namely; their military bases, Kenya’s economic ties to the UK, and the interests of the immigrant populations [25].

The independence government under Kenyatta was, therefore, faced with many internal and territorial problems that may have contributed to the continued stationing of the British military presence in Kenya. Politically, the new regime continued to be faced with ethnic and ideological divisions particularly with secessionist movements and other neighbouring countries’ expansionist policies [26].

Britain was carefully orchestrating these talks and the British government closely monitored these events as they unfolded. In this regard, Britain sought to ensure that the new post-independence Kenya government would be friendly to Britain, it would protect the British interests and as if to lay ground in order to accomplish these ends, Britain sought to negotiate a constitution for Kenya on terms that can only be described as favorable to British interests [27].

For the British, Kenya had been identified as the most suitable location for a theatre reserve after the Suez Canal’s Aden base had been denied to them in a rather dramatic circumstance. A military base had been for some years under construction at Kahawa and with the call for independence, the worry was on the viability of the military base given the fact that they had less than twelve months to conclude independence talks according to Kyle. Kenyatta had to deal with three urgent transitional problems with deep roots in Kenya’s colonial history. There was the Somali secessionist threat soon after independence. With the support of the Mogadishu government, the Kenyan Somalis who had even boycotted the 1963 elections engaged the Kenyatta government in an armed confrontation, in their effort to secede from Kenya. It took Kenyatta three years of military operations against the Shifta to secure the area [28].

The second problem occurred on 12th January 1964 when Kenyan African soldiers mutinied to protest unfulfilled independence dreams and the continued domination of the armed forces by British officers. Kenyatta used regular British officers to end the mutiny, improved the barracks conditions, and elevated many African officers to key positions. More importantly, the military mutiny of 1964 in Lanet revealed the fragility of the immediate post-independence Kenya leadership and army to control and redress the situation. Only when the British military intervened at Lanet did the gesture solidify Kenyatta’s regime and reinforced Kenya’s military diplomatic relations with Britain. The intervention of the 24th Brigade to assist in quelling the revolt demonstrated in no uncertain terms that Kenya still relied upon British military largesse. More so it solidified Kenyatta’s regime and reinforced Kenya’s military diplomatic relations with Britain [29].

As part of their training, majority of the Kenyan military personnel commissioned after independence have attended trainings at Sand Hurst military academy in Britain and therefore, it is not surprising that Kenya’s military remains the most westernized of all the inherited institutions [30].

2.4.1. Moi’s Presidency, 1978-2002

When President Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, Vice-President Moi took over leadership in accordance with the constitutional provisions. While the death of Jomo Kenyatta in 1978 heralded a period of political uncertainty and tension in Kenya, on becoming president, Moi emphasized his history as Kenyatta’s loyal follower, endorsed previous government policies, associated himself with the mainstream capitalist political elite and announced that he would follow in Kenyatta’s footsteps popularly coined as “Nyayo” (Swahili for footsteps) as if to reassure the “wailing” nation of his commitment to the founding father’s vision. Moi’s foreign policy and economic development schemes were that of a continuation of the late President Kenyatta era policies [31].

Whilst Kenyatta’s regime had close ties with Western countries in terms of economic and diplomatic relations, Moi’s regime especially since 1988 had strained relationship with Western countries for what Moi saw as foreign meddling of internal affairs [32]. During Moi’s regime, diplomatic relations with the Eastern bloc improved including the 1980 visit by President Moi to China and subsequent signing of economic and cultural agreements and this marked a significant turn in foreign policy and diplomacy [33]. President Moi, who had repeatedly accused China of plotting revolution in Kenya in the 1960s, lost no time in reaching out to the post-Mao People’s Republic of China. Moi’s main motivation was to diversify the sources of Kenya’s external development funds.

However, President Moi also had his share of rebellion and threat of national security during his tenure as president. In August of 1982, junior non-commissioned soldiers of the Air Force staged a coup against the government, occupying Jomo Kenyatta and Wilson Airports in Nairobi, the general post office, and the office of the Voice of Kenya radio station [34]. Of significance to this study was the comment from the then British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, who was later to remark in August 1982 during the failed Kenya Air force coup de tat that Britain was carefully watching the situation [35]. This comment coming from the prime minister of Britain is significant as it indicated that the role of British soldiers stationed in Kenya could again, therefore, not be ignored.

The country’s leadership was pressured to change the constitution in order to ensure the country held multiparty elections. The repeal of the Kenyan constitution not only rejuvenated the democratic space in the country but also had significant impacts on the political culture of the country [36]. As a show of following in the footsteps of the first president, Moi’s foreign policy and economic development schemes were just those of a continuation of the Kenyatta era policies of relevance to this study, therefore, was the continuity in granting the British military further stationing and training in Kenya. While President Kenyatta had given the British Army, under the aegis of the British Army Training Liaison Staff Kenya a 15-year contract to carry out training in Kenya, in 1988 President Moi renewed it for a period of 10 years. But when the British government joined other Western countries in demanding more democratic space in Kenya, the Moi government reduced the period to five years and subsequently made it three years [37].

The move by president Moi is vital to the study as the said period coincided with the clamor for multiparty politics in Kenya when Western countries pushed forth the repeal of the constitution to allow for multiparty politics in the country. More so at a time when the Moi government had been accused by Western countries of having an appalling human rights record instituted with systematic terror against political opponents, China overlooked these realities as it strengthened its economic relations with Kenya but then so had some Western governments like Britain (until the late 1990s) and France [38].

Like Kenyatta, Moi was involved in direct efforts to mediate internal conflicts in the African sub-region namely, Uganda, Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia and Mozambique. Unlike Kenyatta, President Moi was more active in peace mediation talks and when he assumed the reigns of OAU chairman in June, 1981 at the annual summit referred to as Nairobi I, he quickly asserted himself as a prominent leader in the process to reconcile the Chadian factions. Notably, the conduct of foreign policy under former President Moi was highly centralised and reflected his self-interest in defending his government against international and domestic criticism. Moi thus became more interested in neutralising those perceived to be opposed to him. He centralized and personalized power in the image of the “Nyayo” philosophy that mirrored Kenyatta’s style of leadership and was cloaked in the aspirations of peace, love and unity in an attempt to stand out as a nationalist in his own right [39].

He attempted to exert his regime and Kenya as a pillar in diplomacy in the African region and particularly in the Horn of Africa and the East Africa sub-region by attempting to resolve internationalized conflicts in the region. This was a significant step to shape the direction of Kenyan foreign policy under president Moi. This was demonstrated by the attempt to manage the Uganda conflict that was between Tito Okello’s government and Yoweri Museveni’s rebel group in 1985, that of the Mozambique conflict that was between Frelimo government and Renamo rebel group in 1989 and the management of the Sudan conflict from about 1995 and Somalia conflict from 2000 [40].

Even though the management of the Sudan and Somalia conflicts was not strictly a Kenyan affair, Kenya played a significant role under Moi’s leadership by hosting and providing the chief mediators. Kenya received significant accolades in its diplomacy of conflict management in the region [41]. According to Orwa With the end of the Cold War, the clamor for multiparty politics in Kenya and the push for the repeal of the constitution to allow for multiparty politics in the country dealt a big blow to president Moi regime posture and more so when Western countries exerted pressure on his regime to address these reforms. Foreign interference also took a center stage during Moi’s regime especially with Western countries for what Moi saw as foreign meddling of these countries in internal affairs of Kenya.

2.4.2. Kibaki’s Presidency, 2002-9th April, 2013

With the coming of the NARC Administration, President Kibaki began his term declaring an end to tribalism and corruption, yet only two years after assuming power his government was rocked by corruption and malgovernance allegations, the most notable being the Anglo-leasing scandal. President Kibaki’s administration had committed itself to reforms and change, the desire to shift from the old corrupt networks and traditions that had characterized the former bureaucracy and regime of president Moi [42].The new Kibaki administration had opened up the tendering systems especially on the defence and arms sourcing and an unprecedented anti-corruption wave in the country coupled by an increased public interest on defence issues and budget had rattled the traditional British market sourcing the wrong way [43].

For purposes of military training, Kenya’s military officers have been sent to the UK, Israel and the US. This training has influenced equally the sourcing of arms, with NATO countries supplying 80% of its needs. In addition, Kenya continues since 1964 to maintain direct military links with the West [44].

Regionally, Kibaki’s administration endeared and focused on the EAC revival with renewed interest by other countries in the region, such as Rwanda and Burundi, which applied to join the EAC, and the heads of state of these two small countries have been attending EAC summit meetings [45]. It is under his leadership that the protocol on the establishment of East Africa Standby Brigade (EASBRIG) was formed in February, 2004, when under the auspices of IGAD, the first meeting of the East African Chiefs of Defence Staff adopted a policy framework to establish the EASBRIG that was later approved by the respective Heads of State during the first assembly of EASBRIG meeting held in April 2005 in Addis Ababa Ethiopia.

From the 13 member states of EASBRIG, Kenya was nominated to host the headquarters of EASBRIG. The East African brigade would be part of the African Union’s 15,000-strong African Standby Force to respond to disasters and conflict in the region. The high level of focused partner support particularly from the UK is a powerful asset to the operationalisation of EASBIRG and more so the inception of training cycles at the International Peace Support Training Centre (IPSTC) Karen, Nairobi has assisted in the implementation of the EASBRIG strategy [46].

Internationally, there was renewed building of relations with China by the Kibaki administration, including official high powered delegations exchanging bilateral agreements between the two countries and indeed under President Kibaki, Kenya’s foreign policy underwent a significant shift both in themes and fora. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kenya’s foreign policy was now based on three interlinked pillars: Economic diplomacy, Peace diplomacy and Environmental diplomacy. Kenya’s foreign policy would be informed by the necessity to secure the regional and wider economic objectives and already the Kibaki administration put in place a look-East strategy as a means of reducing their dependence on traditional Western markets [47].

According to Onjala, the forum for pursuing Kenya’s foreign policy has also changed significantly to reflect changes in the international system. One of the factors that have influenced the change in fora of implementing Kenya’s foreign policy is the growth in multilateralism. In addition to the traditional organizations such as the United Nations, Non-aligned Movement (NAM) and African Union (AU), Kenya now has been actively involved in engaging other countries at a multilateral forum such as China under Forum on Africa-China Corporation (FOCAC) Japan under Tokyo International Conference on Africa Development (TICAD) and other Asian countries under New Asia-Africa Strategic Partnership (NAASP). There is a lot of literature on the relationship between Kenya and England covering colonization and post-independence period but a scanty research on the historical Evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military diplomatic relations where this study seeks to trace. The literature reviewed under Kibaki’s Presidency, showed that the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military Diplomatic relations since 1963, was not specifically addressed the gap which this study has filled. The reviewed literature found out that Kenya foreign policy moved towards east.

2.5. Theoretical Framework

Wasike and Odhiambo [48], discuss the role of theories in guiding the thrust of academic studies. They emphasize the importance of theories in offering compelling and incisive causal explanations with calculated precision. They assert that theories play the role of predicting, prescribing and evaluating socio-political phenomena hence they cannot be ignored.

Realist Theory

The study borrowed from realist theory of international relations, to give an analysis of the military relations between the two nations. The leading scholar of the realist school of thought is Morgenthau [49]. He argues that power remains a key variable in the conduct of affairs in the international system. For him, the international system is anarchic since there is no morality in the conduct of affairs and there is no international government to oversee the conduct of affairs by the government. The central government is the main actor in the international system and it engages in internal and external efforts to increase effective strategies and also undertake external attempts to align or realign with other states in order to propagate and protect their own interest and maximize their power. This influences the pattern of interactions that will take place including the number of states to align with each other in opposing groupings as part of a balance of power. Morgenthau argues that since the international system is anarchic by virtue of its structure, there is need for member states and actors to rely on whatever means of arrangements they can generate to enhance their security and survival.

He argues further that as structures change so does interaction and alliance patterns among its members as well as the outcome that such interactions can be expected to produce. Morgenthau views survival and stability as minimum goal of foreign policies that nations pursue. Thus, all nations are compelled to protect their physical, political, and territorial integrity against encroachments by other nations. According to this theory, national interest is akin to national survival. As long as the world is divided into nations, the national interest is indeed the last word in world politics. Nevertheless, Morgenthau argues that since the international system is based on balance of power, nations follow those policies designed to preserve the status quo, achieve imperialistic expansion, or to gain prestige. Anglo-Kenya military diplomatic relations guarantee Kenya support against foreign and domestic enemies as well as its internal security and stability. For example, Britain’s global military posture and security have been enhanced beyond its territories, while Kenya has had its stability and security interests in the Greater Horn of Africa region enhanced as well. Kenya has had intermittent border tensions with Ethiopia and Somalia in the North since independence. Classical realism theory has been criticized for being state-centric; that it downplays the role other non-state actors play in the international system. Critics argue that the role of multinationals and other non-state actors like terrorist groups has been ignored [50]. The weakness of this theory is that it is difficult to evaluate national power and national interest even if we may accept the framework of interest defined as power as the basis for an understanding of international politics, some difficulties; to study national power of a nation is an uphill task and no empirical and theoretical study can help us to correctly evaluate the national power of a nation and the task of analyzing the relative power of different nations like Kenya and Britain. It is also very difficult to factually analyze the national interests of various nations for example; security is regarded as a vital part of the national interest of every nation. But the nature and extent of security that a nation considers to be vitally essential cannot be fully analyzed and explained.

The independent variable in this study was origin and Evolution. The dependent variable was Anglo-Kenyan military diplomatic relations. This relationship since 1963 has fluctuated depending on different circumstances caused by differing on agreements like status of forces agreement (SOFA), goals, interests, rule of law, which when agreed upon by Kenya and United Kingdom through dialogue and reconciliation, institutions and organizations, inclusiveness and transparency stabilized Kenya and United Kingdom and hence were intervening variables in this study.

3. Research Methodology

This section presents outlines the various methodological tools that were utilized in undertaking the study, including; the research design, target population, sample selection and sample size, the research instruments, measurement of variables, data collection methods and data analysis and presentation techniques.

3.1. Research Designs

The study adopted a mixed approach method. The research design was both quantitative and qualitative with the aim of determining the relationship between the origin and Evolution (independent variables) and Anglo-Kenyan military diplomatic relations (dependent variable). On the objective which sought to trace the historical Evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military diplomatic relations, the study used historical research design which included documents analysis (Table 1). The design was chosen since it was more precise and accurate because it involved description of events in a carefully planned way [51]. This research design also portrayed the characteristics of a population fully, Chandran [52] and also according to Mugenda and Mugenda [53], descriptive research determines and reports the way things were.

3.2. Study Area

The study was undertaken in Samburu County which lies within the Arid and Semi-Arid parts of Kenya and has an area of 21,022.1 sq. Km. It is situated in the northern part of the Great Rift Valley. Samburu is bordered by Turkana to the Northwest, Baringo to the Southwest, Marsabit to the Northeast, Isiolo to the East and Laikipia to the South. The county lies between latitudes 0˚30' and 2˚45' north of the equator between longitudes 36˚15' and 38˚10' east of the Prime Meridian. The study area was chosen because it is the main training ground for KDF and BATUK and it has favourable terrain and less populated compared to other places like Nanyuki (Figure 1).

3.3. Target Population

The target population for this study included the British and the Kenyan army personnel training in Archer’s Post. The British Army trains troops in Kenya and prepares for operations in countries such as Afghanistan. The Unit is known as the British Army Training Unit, Kenya (BATUK). It is a permanent training unit with stations in Kahawa, Nairobi (which is a smaller unit) and Nanyuki. BATUK provides logistical support to visiting units of the British Army. It consists of 56 permanent staff and a reinforcement of 110 personnel. An agreement with the Government of Kenya allows six infantry battalions to train in Kenya

![]()

Table 1. Matrix of research design, objective and measurable variable indicator that was adopted.

Source: Researcher (2021).

![]() Source: Samburu Country Development plan (2016).

Source: Samburu Country Development plan (2016).

Figure 1. Archer’s Post military training Areas in Samburu County, Kenya.

annually. They have six-week exercises. There are also three Royal Engineering Squadron exercises which carry out civil engineering projects and two medical company group deployments which provide primary health care assistance to the civilian community [54]. According to one British Ministry of Defence (MoD) spokesperson, the UK has a long-standing, mutually beneficial, defence relationship with Kenya. The troops train in Kenya as part of a 40-year military cooperation agreement. About 10,000 British troops train in Kenya annually. Annually approximately 4000 Kenyan troops train in Archer’s Post military training camp.

3.4. Sample Size

The target population was 319,708 members from the County. This according to Mugenda and Mugenda, is more than 10,000 hence the appropriate number for sampling ought to be 384 as demonstrated in the sentences that follow. However, the sample size one adopts depends on what one wants to know, purpose of inquiry, its usefulness and credibility [55]. In a survey research design 30% of the target population appropriately represents the entire group according to Mugenda and Mugenda. On this basis, 30% of the target population was used in this study of which 384 respondents were sampled (Table 2). It has been established that in a survey research design like this one involves sub-groups [56]. The minimum recommended size of each sub-group is 15 respondents, Samburu East Sub-county has two divisions Wamba and Waso. Archer’s Post military training area is located in Waso division which has four administrative locations which were taken as sub groups (Table 3).

3.5. Sampling Strategy

In determination of sample size, the researcher used the formula provided by Mugenda and Mugenda. While in determination of sample size of sub-groups Gall and Borg formula was used.The formula is presented hereunder.

where: N = desired minimum sample size;

Z = the standard normal deviate at confidence interval of 99% (1.96);

p = proportion in the target population estimated to have the characteristic of church leaders and congregation under Study (0.8);

q = 1-p (0.2) and

d = level of statistical significance of estimates (0.05) for desired precision thus derivation of multi-stage random sample size was

![]()

Table 2. Number of KDF, BATUK officers and household sample size.

Source: Researcher, 2021.

![]()

Table 3. Key informants sample size.

Source: Researcher, 2021.

For Kenyan and British soldiers, the sampling as a process of obtaining a proportion of items from the selected people as representative of those people was used [57]. The selection of a representative sample was made with respect to the inferences the researcher intended to make.

The sample size was determined by the following formula recommended by Nassiuma [58].

where:

n the sample size was the population.

C was the Coefficient of variation (0.5).

e was the level of precision (0.05).

Substituting this value for strata obtained:

For British soldiers

n = 98 British soldiers and for the Kenyan soldiers obtained:

n = 98 Kenyan soldiers.

Therefore, for (local) indigenous peoples residing next to the training camp were:

Whole Sample size

For British soldiers

n = 98 British soldiers and for the Kenyan soldiers obtained:

n = 98 Kenyan soldiers

384 − 196 = 188

Indigenous people (opinion leaders) residing next to Archer’s Post training camp were allocated 188 informants. After the sample size was obtained, the researcher used simple random sampling method, lottery method.This was the most popular method and simplest method. In this method the researcher numbered all the items on separate sheet of paper of same size, shape and color. They were folded and mixed up in a box. A blindfold selection was made. This was done until the 98 British and 98 Kenyan soldiers were obtained which was the desired sample. After obtaining 196 soldiers from KDF and BATUK the researcher used purposive sampling to distribute them in Archer post military training camp. Simple random sampling technique was an appropriate technique because it ensured that all commissioned officers, non-commissioned officers and the local (indigenous) people of those sampled had an equal chance of being included in the samples that yielded the data that were generalized within margin of error that could be determined statistically according to Mugenda and Mugenda. Table 4 summarizes sampling strategies that were used during sample size determination.

3.6. Primary Data

The researcher used both quantitative and qualitative research methods and because of the nature of the research topic, Archival materials, structured questionnaires and in-depth interview guide developed by the researcher were used to collect primary data.

Secondary Data

The secondary data formed literature review in chapter two and was done through critical analysis of books, journals, newspapers, conference proceedings, government/corporate reports, theses, dissertations, Internet and magazines. Secondary analysis is analysis of data by researchers who will probably not have been involved in the collection of data [59].

4. Results

The sections present the research findings and results on the origin and evolution of Anglo-Kenyan military diplomatic relations.

4.1. Origins and Evolution of Kenya-British Military Diplomatic Relations

The evolution of Kenya-Britain relations can be traced back to the British colonial control of Kenya, which began with the Scramble for Africa in 1881. This was followed by the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 that set the rules of colonial occupation and thereafter the partitioning of Africa into various spheres of influence.

According to Pyeatt, midst the geopolitical disputes notable was the 1890

![]()

Table 4. Data collection methods and instruments used in the study.

Source: Researcher (2021).

Anglo-German Agreement better known as the Helgoland-Zanzibar treaty that settled most, if not all, of the complex colonial issues that arose from the ambitions of Great Britain and Ger-many in Africa. While the apparent goal of the treaty signed in 1890 was the ex-change of Helgoland for Zanzibar, the principal motivation was the settlement of Anglo-German colonial boundaries and disputes in Africa, especially in East Africa. These two small islands of Zanzibar and Helgoland (also known as Heli-goland) the former located off the coast of modern-day Tanzania and the latter off the coast of Germany in the North Sea, were strategically included in this accord and had a large role in other inter-European territorial arrangements. The outcome was that Britain would control the North, including Uganda, Germany would control the South. This agreement was formalized and Kenya was now under British authority.

Profoundly, the Berlin conference was instrumental in not only erecting artificial boundaries around present day Kenya, but also in wresting diplomatic initiative from Kenyan people. In 1894 and 1895, Britain declared protectorate over Uganda and Kenya, respectively. Kenya’s boundaries were demarcated without the consultation of Kenya’s people. It can be deduced that the colonial boundaries led to the establishment of a large territorial entity that arbitrarily brought together over forty previously independent communities into one territorial entity [60].

4.2. Britain Interests in Kenya

According to Kanyinga, for Kenya, British interests became well-defined when The Imperial British East African Company (IBEAC) was granted a royal charter in 1888 and the subsequent declaration of the East African protectorate in 1895 so as to forestall the advent of other European powers in the region and to delimit the Sultan of Zanzibar dominion on the mainland. Worth noting is the fact that the political, economic and geo-strategic considerations of the East Coast of Africa had attracted the attention of other major colonial powers besides Britain and Germany all of whom had laid claim to the East Coast of Africa.

The East African Protectorate, which replaced the Imperial British East Africa Company, was created in 1895 and comprised present-day Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika (Tanganyika was colonized by the Germans and became a British protectorate after World War I and later became modern day Tanzania). The notion of Kenya as a colonial state began with the arrival of the British military in 1895. It is imperative to note here that the driving force for the European powers to claim part of East Africa was driven largely by among other reasons, the prestige of possessing a colony outside Europe, resettlement of surplus populations, the search for raw materials and new markets as well as the desire to spread Christianity and more importantly for this study the search for and control of the source for river Nile. A retired senior military officer respondent said that:

The British military presence in Kenya was to dominate us as a colony and exploit economic and geo-strategic for their benefit and to prevent Germany from encroaching into Kenya. The East Coast of Africa had attracted the attention of other major colonial powers beside Britain and Germany all of whom had laid claim to the East Coast of Africa (Interview with a former senior military officer, Nairobi, May 28, 2021).

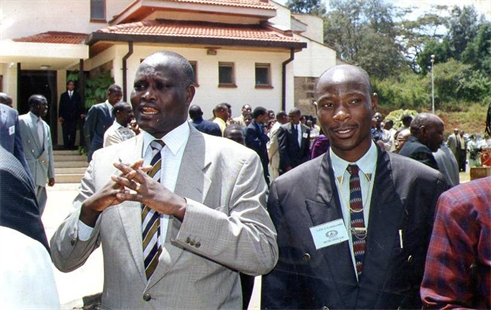

The world’s developed countries like United Kingdom had found a convenient way of dealing with the argument that they were responsible for the depletion of the developing countries resources. The governments of these countries, as well as organizations working on their behalf, regularly release reports proving that they have learned how to make more efficient use of raw materials and, in the process, have reduced the extent of their exploitation of natural resources. Plate 1 shows a retired senior military officer with the researcher during the interview of tracing Anglo-Kenyan diplomatic relations.

The finding that the British were interested in the regions natural resources is corroborated by Olson who found out that the source of the Nile River was especially important to the British strategic defense. They believed that whoever controls the source of the river Nile controlled North Africa and Egypt, and therefore, the Suez Canal and the trade routes to India and Asia according to Olson. It is worth noting that all the Kenyan nationalities resisted British control by waging struggles on many fronts; for example, forces under Waiyaki wa Hinga attacked and burnt the British station in Dagoretti in 1890, the Nandi resistance (the most tenacious of all) led by Koitalel arap Samoei of 1890, the Bukusu resistance of 1896, Giriama resistance of 1900,Gusii resistance 1907 remain hallmarks of the African initial resistances to colonial rule and all of which formed the initial aggressive acts to the British in Kenya.

As a result they became the causes of the first military expeditions and have been explored in depth by scholars like Maxon and Bantley. This East African

Source Researcher, 2021.

Plate 1. A retired senior military officer on the left with the researcher in a black coat on the right, 2021.

protectorate was under a territorial force called the Kings African Rifles (KAR), whose sole mandate was to protect and secure both the economic and strategic interests pioneered by the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC). It is evident that the Portuguese had succeeded in gaining control of much of the Kenyan coast as evident by the vestiges left behind by the Portuguese like the Fort Jesus built in 1593 and the pillar of Vasco da Gama in Malindi. The Portuguese interests in Kenya and East Africa were centred mainly on controlling trade routes to India according to Matson.

Kenya’s strategic location in East Africa and its valuable point of entry into the Horn of Africa had considerably given it more leverage amongst the other East African nations from the onset of colonial control and this fact had featured well in the British interests in the East Coast of Africa. Kenya’s colonial history is unique because Britain’s colonial policy towards Kenya was long-term geared towards resettling a large number of white settler community and making Kenya a white man’s country. The Imperial British East Africa Company, the main commercial administrator of British East Africa, began the construction of the Kenya-Uganda railway at the Kilindini Harbour in Mombasa in 1895 and around 1900, the rail line arrived at current day city of Nairobi and around 1901 it arrived at Port Florence (current day Kisumu city). With the success of the Railway line, the first white settlers began arriving in Kenya as early as 1902. Under the Crown Land Ordinance of 1902 the sale and leasing of land to settlers began [61].

Scholar Dilley opines that this ordinance underlined that the crown had original title to the land, and deserted or vacated land reverted back to the crown. Kenya was declared a white man’s crown colony in 1920 and in light of this development, two parallel dual economies mainly native economy and settler economy on the other hand were established.

Subsequently, the colonial administration saw the need to alienate Africans from their land for colonial settlements in the Kenyan highlands dubbed the “White Highlands” where these white settlers were to occupy and embark on large scale plantation farming to sustain themselves and their economy. Gradually as Leys informs, the colonial administration established itself through several sets of legislations most of which aimed at protecting the interests of the state officials and those of the white settler farmers.

Dilley notes that notable was the Kenya (Annexation) Order-in-Council, 1920 and the Kenya Colony Or-der-in-Council, 1921 that vested all arable land in the British Crown and totally disinherited indigenous Kenyans of their land. These legislations created the reserves for “natives” and located them away from areas scheduled for European settlement and this gave way for the colonial administration first to control and to suppress the envisaged competition from the native African and Asian economies. Locally punitive legislations and taxation laws banning the Africans from cash crop farming were introduced by the colonial authority which forced the Africans to work in the settler farms after they were forcefully evicted from their farms and pushed to reserves where land ownership was not encouraged.

Okoth-Ogendo rightly notes that; The Crown Lands (Amendment) Ordinance, of 1938 gave legal effect to this dual policy of European “White Highlands” (or high potential areas) and African “Native Reserves” (or marginal lands). Within the international system and at the same time, the Second World War (1939-45) broke out, and Kenya being an ally to Britain became an important British military base for successful campaigns against Italy in the Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia. The same British military had conscripted Kenyans to serve their interests during the First World War and the Second World War. This fact is highlighted by Shiroya’s study on the role of African soldiers in World War II when he argues that the African participation posited African soldiers to politically galvanize against colonial rule as a result of their wartime experiences. Notable from Shiroya’s study was that the African soldiers in the war had fought alongside British Soldiers for the freedom of Britain and they felt that they too were entitled to the freedom of their own country, from Britain itself. Shiroya concludes that the military experience of numerous Kenyans was a major factor in the Mau Mau war as was espoused in literature review section, as many ex-servicemen joined the freedom struggle and served in the Mau Mau armies, mostly in leadership positions, having soldiery and battle experiences. To corroborate Shiroya’s findings that Mau Mau had fought the British Soldiers for the freedom of Britain, a retired military officer respondent said:

The BATUK should not have a permanent base since this impairs our sovereignty. We are weak technologically and economically but we got our independence from them in 1963. They should just come and train with KDF and go back to United Kingdom (Interview with a respondent, Nairobi, May 28, 2021).

4.3. Anglo-Kenyan Military Diplomatic Relations and Kenyan Sovereignty

In the mid-1970s, the Anglo-Kenyan Military diplomatic relations appeared to be in decline. There was uncertainty amongst British policy-makers and they no longer had the financial and military ability to pursue their former policies in Kenya like being the sole supplier of military hardware and defending Kenya from any external attack [62]. This was particularly apparent in the military alliances, plans and understandings on which the relationship had previously been built. British defence abilities were decreased, and the 1974-75 Mason defence review planned to reduce defence spending as a proportion of Britain’s gross domestic product from 5 per cent to 4.5 per cent over ten years, whilst focusing on NATO and decreasing manpower [63].

Anglo-Kenyan Military diplomatic relations policies had been premised on Sandys’ 1964 argument that Kenya should not purchase expensive military equipment but rely on British military support if necessary. This was already being challenged, and in 1974 British policy instead became one of supporting an arms build-up in Kenya and turning the Kenyans away from any potential reliance on direct British intervention. In 1974, as in 1970, the Bamburi Understanding which was to defend Kenya against any attack, was renewed with little debate or dissent, but in 1978 the idea of ending the understanding was for the first time seriously contemplated, with gradual disengagement favoured. The key event, however, was Britain’s failure to supply Kenya with ammunition following the Israeli raid on Entebbe. This made explicit the global military and financial weakness of Britain, with the emptiness of British commitments and abilities laid bare.

From 1974 to Kenyatta’s death in 1978, the direct and tangible benefits which had made Kenya such a useful partner for Britain and vice versa seemed in decline. While neither was willing to break this entirely, both sides were reassessing the terms of the security alliance [64] [65]. The Anglo-Kenyan Military diplomatic relations were also slipping, Kenyatta had for so long seemed to offer security for British interests, but from the mid-1970s he was seen less positively. This led some British diplomats, notably High Commissioner Duff, to be particularly pessimistic, and more inclined to criticise than many of his predecessors. Criticisms included Kenyatta’s lack of focus and ability, the growth of corruption, Kikuyuisation, “an increasingly autocratic style of government”, and the possibility that these issues may “seriously reduce the chance of an orderly succession and will become a major threat to the country’s stability” [66]. Kenya had previously been compared positively with other African states on issues such as corruption, but by 1975 “Kenya loses her status as a shining example of democracy in the African gloom” [67].

Over the centuries, scholars, theologians, philosophers and jurists have wrestled with the concept of sovereignty, striving to shed light on its form and functions in human society. Sovereignty tends to fascinate. Implicit in it is a tension of opposites. Literally, sovereignty carries connotations of supreme authority. A sovereign answers to no one and occupies a lofty position above the law [68]. In reality, however, supreme authority is subject to myriad caveats and impossible to reconcile with human imperfection, the intricacies of social organization and the complex demands of government.

The limits of supremacy are particularly stark in the diffuse atmosphere of international relations with its collection of deeply inter-dependent States and entities. Thus, it becomes obvious that sovereignty may be understood only in terms of its limits. More than that, it is a concept that makes sense only if and when those limits are identified, clarified and enforced [69].

The Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years War in 1648, is understood as a critical moment in the development of the modern international system composed of sovereign states each with exclusive authority within its own geographic borders. The Westphalian sovereign state model, based on the principles of autonomy, territory, mutual recognition and control is the basic concept for the major theoretical approaches to international relations, where it is either an analytical assumption or a constitutive norm, and provides a benchmark for analysing variations to sovereignty [70]. According to Westphalia treaty (1648) then, Kenya’s sovereignty is impaired by the permanent stationing of BATUK soldiers since 1963 in Kenya.

Sovereignty is deeply embedded in world affairs as it provides an arrangement that is conductive to upholding certain values that are considered to be of fundamental importance. These include international order among states, membership and participation in the society of states, co-existence of political systems, legal equality of states, political freedom of states, and pluralism or respect for the diversity of ways of life of different groups of people around the world. Jackson asserts that Sovereignty acknowledges the value of international legal equality; i.e., the equal status between independent states. According to a BATUK respondent:

BATUK presence in Kenya shows the partnership between the two countries and the history they share. No country including United Kingdom can claim absolute Sovereignty because the world is facing challenges of fighting terrorism that no single country can win alone (Interview with a BATUK soldier, Archer’s Post, May 19, 2021).

The BATUK respondent who said their presence in Archer’s Post shows the partnership between Kenya and United Kingdom is contradicted by Fowler and Bunck who said to attain sovereignty a state must demonstrate internal supremacy and external independence. That is a sovereign state must be able to show political supremacy in its own territory over all other political authorities and demonstrate actual independence of outside authority, not the supremacy of one state over others but the independence of one state from its peers [71]. Sovereignty, therefore, is the assumption that a government of a state is both supreme and independent. Internal sovereignty is a fundamental authority relationship within states between rulers and ruled which is usually defined by a state’s constitution, and external authority is a fundamental authority relationship between states which is defined by international law. Ultimately it is the international community that determines what are the requirements of sovereignty and which political entities qualify as sovereign states.

The “chunk theory” of applying sovereignty to international politics is identified with the traditional Westphalian outlook and implies two characteristics of state sovereignty, that is, state sovereignty may be viewed in terms that are both monolithic and deductive. First, it is monolithic. A sovereign state enjoys all the privileges of sovereignty simultaneously; it has people, government, and territory, is internally supreme [72]. Second, Fowler and Bunck argue that state sovereignty is indivisible: that is, sovereignty is possessed in full or not at all.

The chunk theory of sovereignty as monolithic and indivisible was corroborated by a KDF respondent who said:

If conceived in these terms sovereignty is absolute. Sovereignty must be present or absent. Regardless of their population size, wealth, or military power, sovereign states benefit from the same legal privileges. Sovereignty is essentially a matter of reciprocity. Each sovereign state, no matter how large or small, has the same rights and duties as all other sovereign states in the same era (Interview with a respondent, Nairobi, May 28, 2021).

Fowler and Bunck says that; Alternatively, the “basket theory of sovereignty” allows a rethink on the question of sovereignty by scholars who view sovereignty not in the absolute terms of a monolithic chunk, but rather in variable terms, as a basket of attributes and corresponding rights and duties. In this model sovereignty exists in degrees, some states processing a certain basket of some attributes, others possess another basket of attributes.

While a few powerful states will enjoy absolute sovereignty, most, by contrast, will find their sovereignty variable, evolving or truncated according to Philpott. When this concept of sovereignty is applied to international relations theory it enables each state’s basket of attributes to be examined empirically to determine the extent of that state’s rights and obligations. To basket thinkers sovereignty is not something that must be possessed in full or not at all; it is accepted that some states can be more sovereign than others according to Fowler and Bunck. This was corroborated by a KDF respondent who said:

The BATUK always think they are superior to KDF and even the Kenyan law. The BATUK soldiers at times break the laws but they are not prosecuted and they do not have immunity. This shows that developed nations undermines sovereignty of developing states like Kenya (Interview with a respondent, Nairobi, May 28, 2021).

In practice, the term sovereignty has been used in different ways. Krasner identified four different meanings of sovereignty in contemporary usage; interdependence sovereignty; domestic sovereignty; Westphalian sovereignty and international legal sovereignty. These are defined as: Interdependence Sovereignty is the ability of states to control movement across their borders; Domestic sovereignty refers to the authority structures within states and the ability of these structures to effectively regulate behaviour. The acceptance or recognition of a given authority structure is one aspect of domestic sovereignty; the other is the level of control that officials can actually exercise.

Well-ordered domestic polities have both legitimate and effective authority structures. Failed states have neither; Westphalian sovereignty refers to the exclusion of external sources of authority both de jure and de facto; and International legal authority refers to mutual recognition. The basic rule of international legal sovereignty is that recognition is accorded to juridically independent territorial entities. States in the international system are free and equal according to Sorensen. Fowler and Bunck have similar criteria which incorporates three of Krasner’s four definitions. They are; a sovereign state must possess de facto internal supremacy; that is, there is a final and absolute authority within the political community; sovereignty implies de facto external independence; that is, no outsider exercises control within its territory; and a sovereign state’s constitutional independence is recognised by other states; that is, de jure independence is essential.

There is duality of sovereignty, which is an internal dimension based on the state and its relationship with its citizens, and an external dimension that administers the relationships amongst states. The two criteria are: Internal sovereignty refers to the concept of state responsibility; that is sovereignty is dependent on the ability of states to provide political goods to its citizens. Internal sovereignty is not absolute but exists in degrees. Well-ordered domestic polities have high levels of state responsibility and total sovereignty. Failed states do not and will find their sovereignty curtailed. External sovereignty consists of two elements: de jure recognition by the international community of a state’s independence; that is, a state in the international system is free and equal; and de facto external independence; that is, no outsider exercises control within a state’s territory according to Sorensen.

4.4. Anglo-Kenyan Military Diplomatic Relations and Responsible Sovereignty

Former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan [73] highlighted the changing nature of sovereignty when he said that “sovereignty implies responsibility not just power”. This concept is very different from the classical international approach which emphasised the authority of the state to intervene coercively in activities in its territory without interference from external actors. The major difference in this concept of sovereignty is the emphasis on sovereignty as responsibility, not authority.

Over the past century, progressively greater curbs have been placed on the understanding of sovereignty in the real world. This trend has been a measure of the evolution of international relations and international law, most notably, the pivotal transition since 1945 to a multilateral global system of common allegiance to the United Nations Charter. The phrase “common allegiance” to highlight the element of mutual responsibility, which is a central characteristic of our modern framework of international relations. This is reflected in UN Charter provisions calling for: “collective measures …”; or for the achievement of “… international cooperation in solving international problems …” Joint action is, indeed, vital to the core mission of the United Nations as articulated by Annan. A respondent from BATUK corroborated Kofi Annan’s position:

Apart from cooperation in pursuit of shared interests, another defining feature of modern international relations is the parity human rights and the international rule of law now share with economic and political questions. The explicit recognition in the UN Charter and numerous other instruments of the inherent dignity and worth of every human being, means that people everywhere, as a matter of right, are within the contemplation of international law and entitled to claim its protections.

The concepts “responsible sovereignty” and “responsibility to protect” are woven from these related strands, namely, the shared responsibility of States acting jointly in the defence and advancement of the UN Charter’s stipulations, and the heightened significance of human rights and fundamental freedoms as normative, international obligations. Together, these precepts substantially circumscribe the scope of the “reserved domain” mentioned in Article 2 (7) of the UN Charter. It is true that the duty to ensure the human rights and protection of people in their own territories still rests with the concerned States and governments as matters “essentially within their domestic jurisdiction”. However, the duty to protect is shared directly by the international community of States and the supra-national institutions to which they belong. This means that the sphere of domestic jurisdiction is no longer entirely exclusive to States and governments as stated by Annan. These considerations affirm another of the Secretary-General’s observations that is also fully acknowledged by the originators of the concept. The responsibility to protect concept makes no claim to novelty. It is a reformulation of principles and obligations found in binding international instruments, and it establishes a framework through which the enforcement of those obligations may be strengthened.

Article 56 of the UN Charter articulates the pledge of all UN members states to “take joint and separate action” to achieve the UN’s purposes. Article 1, common to the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, requires States “to respect and ensure respect” for international humanitarian law. And there is as well the international law concept of “universal jurisdiction” under which particular breaches of law may be prosecuted and punished by any State that acquires custody of a violator.

These and other similar rules existed long before “responsible sovereignty and the “responsibility to protect” were conceived and are, in fact, the legal grounding for these relatively new concepts. This means that the new concepts partake of the strengths as well as the weaknesses of the pre-existing legal framework, on which it relies for its enforceability. Unfortunately, it is the weaknesses that have been most striking in the Palestinian experience according to Sorensen. The utility of responsible sovereignty is applicable where the universal human rights of a particular sovereign state are curtailed. Since these rights are not curtailed in Kenya, BATUK presence in Archer’s Post have impaired Kenya’s sovereignty. According to this concept of sovereignty, Odhiambo et al. [74] in their article “The Reprisal Attacks by Al-Shabaab against Kenya” argued that: