Research on EAC-China Economic Relations in Trade and Its Influences: An Analysis Based on Trade Intensities ()

1. Introduction

Since the founding of the EAC, China is one of the largest trading partners of Tanzania and Kenya while Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda have seen massive increases in both trade and investment from China in the last decade. Hence, the EAC is a good example of how regional cooperation has fostered a strategic relationship with China (Esterhuyse et al., 2014). According to Alyek-Omara (2012), to across China’s fast growing request for resources and excess afford of consumer goods, a solution has been to associate with and reinforce trade relations with economic blocks as the EAC; in order to examine and find out new markets to provide services, technology and goods—with this of course being done in return for divers commodities and resources. Therefore, over 2011, China’s government has marked Framework Agreements about Economic and Trade Cooperation to both EAC and ECOWAS, to stretch out cooperation in promoting trade facilitation, direct investment, cross-border infrastructure construction and development aid (China Daily, 2013). Korsak (2017) in his recent research paper has mentioned that the EAC which was composed by five countries at that time started its own common market for goods, labor and capital inside the community in 2010, with the objective of a common currency and full political federation in 2015. The Study conducted by Gigineishvili, Mauro, & Wang (2014) revealed that over the past decade, the EAC’s economic rise performance has been awesome at 6.2 percent, the EAC’s average growth rate in 2004-2013 is in the top one-fifth of the distribution of 10 years growth rate episodes experienced by all countries worldwide since 1960.

Authors and international studies have conducted research on economic cooperation in the field of trade. On the one hand, researchers focused on assessing trade cooperation based on appropriate bilateral trade index Munemo (2013) used the trade complementarity (TC) index & the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index to calculate trade between China and South Africa and concluded that tariff liberalization alone is inadequate for successful trade integration and that it is necessary to improve trade complementarity, reduce barriers to intra-industry trade and liberalize parallel MFN trade. Vahalík (2014) employed indices of trade complementarity and regional trade intensity to assess bilateral trade flows between EU-ASEAN and China-ASEAN; and concluded that china preserves better standing to the ASEAN countries from the angle of trade intensity but in the instance of trade complementarity the EU obtain greater long term results than China. Li (2018) utilized the export similarity index, trade integration index, revealed comparative advantage index, the specialization of the revised coefficient index and coefficient of consistent index to examine China-India Trade Competition and Complementary; and concluded that the trade structure of China-India has some competition, but also has plenty of complementarity. On the other hand, researchers led to the analysis of bilateral trade between countries or regions using the models. Liu & Jiao (2006)examined the effect of understandings trade regional of china along with Australia on trade commodity by employing a model partial equilibrium to estimate the relationship between China’s trade with Australia and concluded that the beginning of regional trade agreements affected China’s commodity trade with Australia. Dembatapitiya & Weerahewa (2015) used a Gravity model to assess the effects of various forms of trade agreements on bilateral trade of South Asia; and the results propose that share out a joint language, a joint colony, together with membership of WTO positively and significantly affect export values. Uzair & Nawaz (2018) examined Modelling well-being impacts within China-Pakistan free trade understandings by employing data involving the total imported commodities and they deducted that rise in Trade along with China beneath customs duties reduction lead to trade establishing and initiating welfare.

The deep motivation for the choice of the subject as well as its model for the in-depth analysis is that through reading a lot of literature, we found that no scholars presently did any research on the economic relations in trade between EAC and China by using the import intensity index and the export intensity index. Moreover, the writing of this study will provide a right comprehension of the components influencing the bilateral trade, find out the problems existing and strategies to enhance the current trade situation. In addition, it will afford guidance for further development of trade relations between EAC and China. This study consists of the following sections: Section II presents the development of trade between EAC and China; Section III discusses the Analysis of China-EAC Trade Intensities, 2000-2019; Section IV provides the potential trade advantage between China and EAC; Section V includes the general conclusion and recommendations.

2. The Development of Trade between EAC and China

2.1. Current Situation of EAC-China Trade Relations

The trade relations between Burundi and China were established in 1963. Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi, during his visit to Burundi on Jan. 11, 2020, said: “China is willing to carry out mutually beneficial cooperation with Burundi under the framework of jointly building the Belt and Road and implementing the eight major initiatives proposed at the Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), with a focus on infrastructure construction and agriculture (Xinhuanet, 2020)”. Kenya, meanwhile, has become an ideal regional area for Chinese investors to increase their business and cooperation in the East Africa. Currently China is offering favorable loans to Kenya, building hospitals and schools for less developed areas. China and Rwanda have signed in 1983 an agreement on setting up a mixed commission for economy and trade cooperation. In 2016, China’s non-financial direct investment in Rwanda attained beyond $100 M inclosing in the fields of digital television and clothing fabrication, and Sino-Rwanda trade flows rose to $157 M in 2017. Currently, to support Rwanda’s exports, China instituted a duty-free policy on 95% of Rwandan products (How Africa News, n.d.). Diplomatic relations between South Sudan and China were established on January 4, 1959. China is one of South Sudan’s largest trading partners with the signing in November 2011 of bilateral trade, economic and technical agreements. In addition, the Joint Bilateral Economic and Trade Committee was established and in October 2012 around 60 Chinese-bankrolled companies have registered in South Sudan (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in South Sudan, 2012). Sino-Tanzanian relations have witnessed a long-term healthy and steady development since the establishment of diplomatic relations on April 26, 1964. “In recent years, China remains Tanzania’s largest trading partner, with 19.3% of Tanzania’s imports in 2017/2018 originating from China. China is also Tanzania’s largest source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) with investment stock of over 700 projects valued at USD 7.1 billion and creating over eighty-seven thousand (87,000) jobs (IPP Media, 2020)”. Uganda and China relationship was created in 1962. China has been Uganda’s important trade partner for wholly some time, and is its second greatest source market. During the past years, the import of China to Uganda has increased from $622 million in 2013 to $886 million in 2016 and the export of Uganda to China have declined in recent years, from $66 million in 2014 to $27 million in 2016; according to the Uganda Ministry of Trade, Industry and Cooperatives.

Overall, the direction and pattern of trade of the three member countries and founder of EAC are consistent with their level of development. After the entry into force on 7 July 2000 of the Treaty established the Community, we notice that China was not yet among the main trading partners of the EAC. The EAC exported mainly to EU and mostly import from Africa and the Middle East. However, according to EAC’s Trade Policy Review 2019 (viewed on Table 1 below), China is the first supplier country of EAC (21.3% in 2017) followed by India, the European Union and the United Arab Emirates. Different from the ranking of import trade partners, China ranks the eighth among the EAC’s major export trading partners, and the EAC’s total exports to China represent 2.4% of the EAC’s total exports in 2017.

As stated in Table 2 of the Trade Policy Review of the EAC, the trade between the EAC and China has been increasing in these recent years, the total value of the trade (2011-2017) from the EAC to China is 4.2 USD billion and the total value of the trade (2011-2017) from China to the EAC is 37.3 USD billion. Therefore, the EAC still has a deficit in the trade with China because they import more than they export.

2.2. China-EAC Trade by Commodities

China imports a certain amount of coffee and cotton from Burundi and exported to Burundi cotton rags, bicycles, metal products, agricultural tools and building materials and so on (World Integrated Trade Solution, 2020).

In recent years, the trade value between China and Kenya has increased dramatically. China exports to Kenya household electric appliance, industrial and agricultural tools, textile products, products for daily use, construction materials and drugs, etc. Chinese imports from Kenya consist mainly of black tea, coffee and leather goods, etc. (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Kenya, n.d.).

Rwanda’s exports to China consist mainly of minerals, hides and skins, tea,

(USD billion and %) ![]()

Table 1. Extra-EAC trade by major trading partners, 2011-2017a.

aExcluding EAC member States. bIncluding re-exports (WTO Secretariat, 2019).

![]()

Table 2. EAC-China trade value, 2011-2017.

Authors’ Calculations modified after (WTO Secretariat, 2019).

coffee and pyrethrum, a flower used to make insecticides while the country imports electronics products, machinery and light industry products (Ntambara, 2015).

South Sudan mainly import from China vehicles, machinery, electrical appliances, pharmaceuticals, plastics, beverages, raw Sugar and cereal flours. The country mainly export oil (Societe Generale, 2020).

Tanzania imports a variety of products from China, including rubber tires, motorcycles, tractors, and iron structures. Chinese imports from Tanzania, include: dry seafood, raw leather, log, coarse copper, wooden handicrafts (TanzaniaInvest, 2020).

The main exports from China to Uganda are machinery and electrical equipment and Uganda’s exports to China mostly consist of many raw goods such as hides, oils and seeds (Vision Reporter, 2014).

3. Analysis of China-EAC Trade Intensities, 2000-2019

Trade intensity index is described like the part of one country’s trade with other country, split by another country’s share of global trade. Trade intensity index is employed to establish if the trade value betwixt two countries is upper or lower than what would look forward over the basis of their significance in world trade. The indexes of export and import intensities are the two parting of Trade intensity index used to examine the structure of exports and Imports.

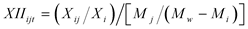

In this chapter, the trade intensities between China-EAC are estimated using time series data of China and EAC for the years 2000-2019. We then calculate the intensity of trade between China and the EAC countries based on the formulas of the export intensity index (XII) and the import intensity index (MII) proposed by Kojima (1964) & Wadhva & Asher (1985) to study and analyze the bilateral trade with the results being reported in Table 3 & Table 4.

3.1. The Export Intensity Index (XII)

The Export intensity index of China relative to each EAC Countries (XIIijt) is shown as follows:

where:

XIIijt = Export intensity index of China relative to each EAC Countries;

Xij = Total exports of China to each EAC Countries;

Xi = Total exports of China;

Mj = Total imports of each EAC Countries;

Mw = Total World imports;

Mi = Total imports of China;

t = 2000 to 2019.

The numerator of the formula, Xij/Xi reflects the proportion of total exports of China to each EAC Countries as a percentage of its total exports. This shows to us how important the bilateral trading partner is to China’s exports. The denominator, Mj/(Mw − Mi), is the total imports of each EAC countries as a proportion of total World imports minus the import of China.

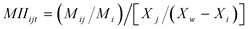

3.2. The Import Intensity Index (MII)

The Import intensity index of China relative to each EAC Countries (MIIijt) is shown as follows:

where:

MIIijt = Import intensity index of China relative to each EAC Countries;

Mij = Total imports of China from each EAC Countries;

Mi = Total imports of China;

Xj = Total exports of each EAC Countries;

Xw = Total World exports;

Xi = Total exports of China;

t = 2000 to 2019.

Similar to the XII, the numerator of the formula, Mij/Mi reflects the proportion of total imports from China to each EAC countries as a percentage of its total imports. This shows to us how bilateral trading partner is important to China’s imports. The denominator, Xj/(Xw − Xi), is the total exports of each EAC countries as a proportion of total World exports minus the exports of China.

The average value of the export/import intensity index is 1. When the value is 1, it would indicate that China exports/imports to each EAC countries in accordance with trading partners’ purchasing power. A value greater 1 indicates a high degree of trade intensity between China and each EAC countries, whilst a value less than 1 represents low trade intensity partnership between China and each EAC countries.

While doing research, several studies have been employed trade intensity indices in academic work since Brown (1949) & Kojima (1964) evolved this method. In its analysis of world trade flows’ intensity, Yamazawa (1970) mentioned that the high intensity of trade reflects such various factors as the strong complementarity in comparative advantage structures between the pair of countries, smaller geographical and psychic distances between them, and mutually favorable agreements between them, and a low intensity of the country situation. Across a survey of the literature on the determinants of bilateral trade levels which discusses the various methods, Drysdale & Garnaut (1982) identified the intensity approach to analyze the resistances of bilateral trade flux in many country world and concluded that the intensity approach identifies gaps in resistances through various bilateral trade relations, and the revue of these gaps supply fertile field for analysis of the nature and relative importance of the divers kinds of resistances to trade. Being part of one of two approaches adapted in his study, Bano (2002) used the intensity of trade index to examine the force of trade relations betwixt New Zealand and the other countries and concluded that intra-industry trade betwixt New Zealand-Australia has risen, and the bilateral trade flux betwixt New Zealand, Australia and Nations else became most intensive but have lessened in certain instances.

More recently, a number of scholars have also used trade intensity indices to identify the strengths (or weaknesses) of trading relationships. For example, Sundar Raj & Ambrose (2014) have employed a trade intensity to evaluate force and nature of bilateral trade relation betwixt India and Japan and saw that intensity betwixt the two Nations is weak. Nevertheless, by the analysis wrought it is evident that the two Nations own important trade potential to collect betwixt them. Ademuyiwa et al. (2014) utilized “a trade intensity analysis” to examine the bilateral trade between Ethiopia and the BRICS countries in 1995-2012; and have concluded that BRICS countries are getting risely significant trading partners to Ethiopia, particularly as Ethiopia’s imports sources. They suggested that Ethiopia more intense trade along with BRICS will afford it a scope to harness its natural resources and utilize the profits to expand worth strings within else commodity ranges. Goyal & Vajid (2018) used the Trade Intensity to quest the major tendencies of bilateral trade betwixt India and UAE and founded that the Trade between India-UAE is on the right track and is more intense in comparison together with its other trading partners. Keeryo, Mumtaz, & Dayo (2020) used trade intensity index to examine the force and nature of Pakistan-India’s bilateral trade relation and noticed that the two countries own a big potential to improve their bilateral trade but possess certain barriers. They suggested that the two nations strengthen their mutual trust and cooperate in matters between them, in order that bilateral trade can be upgraded.

3.3. Data Sources

Data on World’s total import/export, China’s total import/export and EAC Countries total import/export are collected from World Trade Organization database except data on South Sudan’s total import/export which are collected from World Bank Data. Furthermore, data on China’s imports/exports to EAC countries are collected from United Nations Commodity Trade Database.

3.4. Trade Intensities Analysis

According to the collected trade data from WTO database, World Bank Data & UN Comtrade Database, trade intensity indices were calculated for EAC countries by the years 2000 through 2019. The results by country are reported in Table 3 & Table 4 and described below.

Burundi: The export intensity index of China to Burundi in 2000-2019 is less than 1, indicating that China and Burundi have weak export trade ties and the degree of relation in exports is not high. In addition, the degree of trade ties has undergone volatile fluctuations, which shows that the trade relations have not progressed well overall. The import intensity index of China to Burundi in 2000-2019 is lower than 1 except in 2011 as shown in Figure 1, indicating that the import trade links between China and Burundi are weak also and have a trend of decreasing year by year.

![]()

Table 3. The imports intensity indexes (MII) of China to EAC countries 2000-2019.

(Source): Authors’ calculations.

![]()

Table 4. The exports intensity indexes (XII) of China to EAC countries 2000-2019.

(Source): Authors’ calculations.

In general, the import and export intensity index of China to Burundi decrease from year to year. Considerable efforts should be made to stimulate the bilateral trade volume between the two countries.

Kenya: The export intensity index of China to Kenya in 2000-2019 is greater than 1, which shows that China and Kenya have strong export trade ties and the degree of relation in exports is too high. Contrariwise, the import intensity index of China to Kenya in 2000-2019 is lower than 1, showing that the import trade links between China and Kenya are weak and the degree of import relations is not high. Despite that, the degree of trade relations has been increasing year by year, which shows that the degree of trade ties is gradually close and there is the possibility of in-depth development.

Overall, the import and export intensity index of China to Kenya has been growing year by year. It can be observed that the import and export trade between the two countries will continue to grow in the future, which serves a good prospect for the development of bilateral trade.

Rwanda: On the one hand, the import intensity index of China to Rwanda in

![]() (Source): Authors’ calculations.

(Source): Authors’ calculations.

Figure 1. Import Intensity Indexes of China to EAC countries.

2000-2019 is high than 1 even if it regresses from 2015 (Figure 1), showing that the import trade links between China and Rwanda are great and the degree of relation in imports is too high. On the other hand, the export intensity index of China to Rwanda in 2000-2019 is less than 1, showing that the export trade links between China and Rwanda are weak and the degree of relation in exports is not high. In spite of that, the level of trade ties is increasing year by year, which means that the level of trade ties tightens continuously and there is a possibility of deep developing.

Generally speaking, the Trade Intensities of China to Rwanda has been growing year by year. It can be observed that the import and export trade between the two countries will continue to grow in the future, which is a good approach, for the development of trade partnership.

South Sudan: After gaining independence in July 2011, South Sudan and China officially began the trade partnership on Nov. 22, 2011. The export intensity index of China to South Sudan in 2014-2019 is lower than 1, revealing that the export trade links between China and South Sudan are weak and the degree of relation in exports is not high. Regardless of that, the degree of trade ties has been increasing year by year; which shows that the degree of trade ties is progressively close and there is the potentiality of thoroughly development. The import intensity index of China to South Sudan in 2014-2019 is greater than 1, which shows that the import trade relation between China and South Sudan is important even if the degree of trade ties decreased from 2017 as shown in Figure 1. In nutshell, the import and export intensity index of China to South Sudan has been growing year by year. We find that the import and export trade between the two countries will continue to grow in the future, which offers magnificent predictions for the progress of bilateral trade.

Tanzania: The export intensity index of China to Tanzania in 2000-2019 is greater than 1 and the level of exports between the two countries has increased year by year; which means that China and Tanzania have strong export trade ties and the degree of relation in exports is too high. However, the import intensity index of China to Tanzania in 2000-2019 is lower than 1 except the unexpectedly values greater than one for the years 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2013 (shown on Table 3 above). This shows that the import trade links between China and Tanzania is generally weak and the degree of cooperation in imports is not high.

Uganda: The import intensity index of China to Uganda in 2000-2019 is less than 1, indicating that China and Uganda have weak import trade ties and the degree of relation is not high. In addition, the degree of trade ties has undergone volatile fluctuations, which shows that the trade relations in imports have not progressed well overall. The export intensity index of China to Uganda in 2000-2019 is lower than 1 except in 2016 as shown in Figure 2 below, indicating that the export trade links between China and Uganda is weak but have a trend of increasing year by year; which shows that the degree of export trade ties is gradually close and there is the possibility of in-depth development.

3.5. China-EAC Trade Problems and Their Solutions

Based on trends of export intensities and import intensities between China and EAC Countries shown on Table 3 & Table 4 above, we can mention that Export

![]() (Source): Authors’ calculations.

(Source): Authors’ calculations.

Figure 2. Export Intensity Indexes of China to EAC Countries.

and import intensities have overall increased over the years but have been marked by some variations. However, China’s export intensity with respect to EAC Countries has declined over the years only for Burundi from 0.632 during 2000 to 0.515 during 2019. We can deduct from such a downward trend that China has not been able to intensify its export basket over the years to Burundi market. This is largely explained by the fact that Burundi is currently facing the existing problems related to poor results in the infrastructure dimension in terms of the AfDB’s infrastructure development index and by its weak global air connectivity. Moreover China’s import intensity compared to EAC Countries has declined during the years only for Burundi from 0.617 in 2000 to 0.569 in 2019, Rwanda from 1.392 in 2000 to 0.238 in 2019 and South Sudan from 9.809 in 2000 to 4.115 in 2019. We can explain this downward trend in imports to the fact that these three EAC countries record insufficient performance in terms of imports of intermediate goods, hence they end up with fewer manufactured products; and therefore few final goods. This clearly shows that these countries hold small shares in terms of trade and exports.

In view of these above-mentioned problems slowing down the good trade partnership between China and some of the EAC countries, considerable efforts must be made in these countries as well as the EAC as a whole even if the trade intensity between China and the EAC have indeed evolved overall. We suggest that the community must insistently improve its productive capacity in order to consolidate its trade intensity; this means that EAC Countries have to perform enough endeavors to branch out exports and enter the Chinese market because, in the current state, China offers to EAC Countries a large potential market. At the end china’s bilateral trade with the EAC countries will certainly progress much further than it is presently.

3.6. Extra Observations on China-EAC Economic Relations in Trade

Despite fluctuations, the trade intensities between China and EAC increased over the years 2000-2019 for Kenya, Rwanda and South Sudan, but decreased for Burundi while for Tanzania and Uganda only the export intensity index increased compared to the import intensity index which has decreased. The increase in trade intensities over the years 2000-2019 is very evident, as shown in the values of exports and imports and as measured more rigorously by the trade intensity indices. Increased bilateral trade between China and the EAC member states of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda is particularly evident, which can be easily explained by the fact that China has entered into bilateral trade agreements with the EAC Countries.

4. Potential Trade Advantage between China and EAC

4.1. China-EAC Comparative Advantage

In China, labor- and land-intensive industries such as manufacturing are what gives the country a comparative advantage. Many foreign firms such as Nike and Foxconn choose to locate their productions in China because of the lower opportunity cost to lower their cost of production and maximize revenue of their products.

China’s trading pattern is often seen as an illustration of the power of the Heckscher-Ohlin approach to explaining world trade: labor abundant China specializes in exporting labor intensive goods. A broader Heckscher-Ohlin worldview is also perfectly consistent with China’s role in performing the labor-intensive tasks in complex international supply chains. A key prediction of the theory is that relative transport costs by product and export destination influence China’s export success. In particular, the gravity model predicts that China will tend to export “heavy” goods (those with a high transportation cost as a share of value) to nearby export destinations, and will export “light” goods to more distant markets because it has comparative advantage in heavy goods in nearby markets, and lighter goods in more distant markets. Furthermore, heavy goods will be sent by ship, while light goods may be shipped by air (Harrigan & Deng, 2008). Chinese trade also requires accounting for local comparative advantage: products where China has a competitive advantage in some locations but not others.

Chinese manufactured products with comparative advantage in both world and US markets are increasing. Most of the products with comparative advantage are low technology (LT) products; the comparative advantage of Chinese medium technology (MT) products has largely improved in the world market; as a whole, Chinese manufactured exports are of greater comparative advantage in the world market than in the US market. Precisely, low technology (LT) products have the same position in world and US markets, while medium technology (MT) products and high technology (HT) products obviously have a greater comparative advantage in the world market (Hao & Zhao, 2012).

Kenya and Burundi both specialize in cut flowers. Uganda and Burundi both also specialize in cotton. Rwanda and Burundi both specialize in the same product, tungsten ores and concentrates. There is also a comparative advantage in the quality of tea (Chingarande, Mzumara, & Karambakuwa, 2013).

Burundi has a comparative advantage in the quality of the coffee. The EAC countries have a comparative advantage in tea, coffee, cotton.

The EAC exports progressively declined up to the lowest point around 1992-1994, again a general fall in export was recorded in 2002; followed by a modest growth up to date. They are two coffee export leaders in EAC, which are, Kenya and Uganda but with a quasi-dominance of Uganda since 1995. Burundi and Rwanda were the least coffee exporters in EAC because of limited factor endowment (land) and technology, though coffee was grown in a favorable environment and volcanic soils. While Burundi’s coffee export was greater than that of Rwanda since 1980, their export trends intertwined from 2003 onwards. The implementation of Rwanda’s coffee reforms and success attracted FDI which boosted its export (Ndayitwayeko et al., 2014). A rise in exports registered during 1986 and 1995 resulting from the severe rime and damage to the coffee crop of the leading exporter, Brazil, the coffee shortage of which pushed the Arabica coffee price up. This led to high volumes of coffee exports from Brasil’s coffee export competitors, EAC countries being among them (Ndayitwayeko et al., 2014: p. 142).

Balassa’s RCA index was used to establish member states’ comparative advantage. There is therefore evidence that all the members of the EAC have revealed comparative advantage. However, the product number in which they have comparative advantage is small and also produce the same products thereby restricting intra-EAC (Chingarande, Mzumara, & Karambakuwa, 2013). “In the modern theory of international trade, the comparative advantage of the different countries is explained not by the difference in technology, but by the difference in the factor endowments. Such a modern theory is generally known as Heckscher-Ohlin theory, because the groundwork for substantial developments in the theory is laid by (Negishi, 2001)”. “The proponent of the theory of comparative advantage, it is stated that absolute production cost difference rather than comparative cost difference is the reason for international trade. Thus, even if a country has absolute advantage in the production of goods, it can gain by importing the relative dearer good and exporting the relative cheaper good (Beyene, 2014: 164)”.

Generally, the EAC member states and China are gaining from international trade.

4.2. The Belt and Road Initiative

The BRI consists, on the one hand, of the Silk Road Economic Belt, which refers to the land connection through Central Asia and Europe and on the other hand is the 21st Century Maritime Silk, a connection through Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa, and, finally Europe (Figure 3).

Beneath the sponsorship of the BRI, 105 countries and international organizations have signed 123 documents. This involves 37 African countries and AU.

Over the past five years to June 2018, the trade volume between China and BRI countries has grown to over US$5 trillion. “Chinese FDI through the BRI has amounted to US$70 bn and over US$500 bn worth of Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) contracts were signed. More than 82 trade cooperation zones have been established, which in turn have created 244,000 jobs for host countries (Marais & Labuschagne, 2019)”.

The East Africa inshore area has been lead inside the enlargement of China’s sphere of trade impact across linking it to the so-called Maritime Silk Route. The Construction Trends report of Africa proves that the focus on activity by Chinese financiers and builders in Eastern Africa, particularly in the Shipping, transport & Ports sectors (Figure 4).

The major projects in the East Africa are the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway in Ethiopia, the Nairobi-Mombasa railway in Kenya.

In Tanzania, the Bagamoyo port actually underneath construction, is whole to become the greatest in East Africa. The partnership between Tanzania, Oman and China, the port is looking forward to existing in operation by 2022. Situated right 75 km from Dar es Salaam, it has links with a SEZ for export-oriented fabrication.

With an estimated cost of 3.2 billion dollars, the Nairobi-Mombasa railway was opened in June 2017 to replace the 4000 trucks that use the road daily. A lot of trucks use the road daily not only within Kenya but also from others EAC countries especially Burundi and Rwanda (Githaiga et al., 2019). As a part of a broader regional integration Agenda, China invests also in boosting the ambitiousness of EAC’s railway projects. The intent is to stretch out the railway to Ugandan capital, Kampala and then south to Kigali in Rwanda.

“According to the World Bank, a 1 percent reduction in trade costs is likely to increase bilateral trade between economies that participate in the BRI projects by 1.3 percent. The improvement in the network and capacity of railways and other cross-border transport infrastructure could therefore lead to more intra-African trade, as well as increased investment, the associated technology and skills transfers, and higher growth in African economies (Sylodium, 2020)”.

4.3. The China-EAC friendship

1) Culture Exchange

EAC leaders held up the concept that learning about Chinese language and culture upgrades employment competitiveness and eases best trade relations with China. The establishment of Chinese language into EAC countries’ school programs shows China’s rising impact on the Community as a worldwide superpower.

In Burundi, the Chinese Confucius Institute at the University of Burundi plays an important role in spreading the language, with many Burundian Chinese-speaking students praising the impact the institute has had on their lives and a taste of the language Chinese culture. Kenya has set up a program from 2020 which includes the learning of Chinese language as an optional subject in elementary schools. Nevertheless, Kenya remains the last country in the East African community to follow this tendency of establishing Mandarin in schools. The influence of the Chinese language in Rwanda has recorded significant recognition in its bilateral relationship with China. This comes off with the 12th edition of “Chinese Bridge”, a Mandarin proficiency contest welcomed by Rwanda in June 2019 and held for high school students. Chinese soft power is presented in South Sudan through its Confucius Institutes, humanitarian projects, and development assistance. Uganda is yet the solely country in EAC to include the Chinese language as a compulsory school subject. The former Tanzanian President John Pombe Magufuli declared in May 2019 that Chinese language had been appended to the Secondary Education Certificate Examination and that students should grab that Chinese language exam.

Overall, the Confucius Institute offers a better understanding Chinese language and Chinese culture to EAC citizens. Therefore, it helps in their localities to build and promote friendly relationship in different areas.

2) The Infrastructures

Infrastructure is a challenge for regional integration and market access in the EAC and the Chinese are good in the construction, engineering area. Although in the EAC, the largest partner in infrastructures and investments with China are Kenya and Tanzania, there are still a shortage of roads, building, ports especially in Burundi and Rwanda. There are many infrastructure and investment projects in the EAC: the main ones are the TAZARA project and the Bagamoyo port project which will be the largest port in the EAC when completed and is mainly funded by a Chinese government; but TAZARA project is currently the most important because the citizens of the EAC started to use the train.

These projects are benefit to the EAC countries in investment in railroad infrastructure significantly with reducing the costs of trading goods: the goods and commodities from China to the EAC will be cheaper but also from the EAC to China.

Overall, TAZARA provides a communication support for the three regional groupings as EAC, SADC and COMESA. It helps the trade, the exchange of goods & services between the countries of those regions but also the imports of goods outside the continent specifically in China. For importers & exporters in the Central & Southern African neighbourship with trade links to the nations in the Middle East and Asia, without forgetting china, TAZARA supplies the briefest way to the sea, across Dar es Salaam port and thus constitutes a vital railroad linkage. The TAZARA project also is a benefit of the whole East African Community especially the landlocked countries like Burundi and Rwanda because Tanzania is their neighbor country, it’s easy for those countries to take advantages of the TAZARA railway station for example for the imported products will be reduced and the transportation won’t cost much as before the construction of the railway.

3) Medical aid

Chinese government funded in 2008 the construction of Mpanda General Hospital and committed to provide the necessary materials for the equipment of this establishment, drugs for antimalarial as well as the deployment of the personnel to the hospital. Other projects include the construction and equipping of a Malaria treatment center in Bujumbura that was established in 2008. The completion of the facility came with additional donations of Malaria drugs (ACT) donated by China to the Republic of Burundi. The Chinese government is giving a training of health care force in Burundi by providing postgraduate scholarships and by accomplished training and skills transfer by the Chinese medical crews sent to Burundi (Gikiri, 2017).

Chinese Government donate medicine, health supplies, paper mill and other health consumable merchandise to Kenya. Through the Chinese government scholarship program, many Kenyan health care workers travel and do their training in China. Similarly, there are specific institution-to-institution collaborations between Kenyan tertiary institutions and their Chinese counterparts. Comprehensive Malaria Prevention and Control Trainings have been conducted in Kenya by Chinese experts.

Sino-Rwanda health relations started in the early 1980s. Since then, two district hospitals have been built with funding from the People’s Republic of China. One of these two hospitals, Masaka Hospital, which was completed in 2011 is intended to be the Central Hospital of Rwanda. Other schemes which have engaged the involvement of the Chinese include a Polyclinic constructed in Masaka and China started sending medical teams to Rwanda in 1982.

The oncoming of medical crews in Southern Sudan ascend to the early 1970s. Medical crews from China have been working in Juba, Wau and Malakal regions. Prolonged conflict occasioned by the civil war in Sudan led to the discontinuation of medical teams to Sudan in 1985, but the resumption materialized later in 2012 after the signing of a new memorandum of understanding on health aid. After gaining independence, a medical staff from Anhui province went to South Sudan at the Juba Teaching Hospital. The current Chinese Medical crews in Wau and Juba offering is not only treatment but equally the formation to native medical staff and internships. The Chinese medical staff detached to the Wau teaching hospital took liability for ensuring that most of the medical equipment and machines at the hospital were restored to functionality.

Tanzania has benefited from China sending experts to offer training to its health workers through the Medical teams seconded from China and through annual scholarships provided to Tanzanians to study in China. In 2009, China funded the establishment of a Malaria Treatment Center at Leah Amana Hospital. This Center is also used for the training of Tanzanian health workers.

Uganda has obtained some medical donations of China into the form medicines of Antimalarial collected in various facilities as Mulago hospital, Jinja Hospital and the China-Uganda friendship Hospital in Naguru. China also give donations of reproductive health medical material, computers and monetary donations have been sent to the Mulago Hospital.

5. General Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

This study has examined the strength, magnitude and direction of bilateral trade between EAC and China. Our findings show that EAC and China trade has intensified over the years, even if it has been marked by fluctuations. The method that has been used during this study namely the trade intensities clearly supports these conclusions.

The community’s comparative advantage is low and it also produces the same products thereby restricting intra-EAC but generally, the EAC member states and China are gaining from trade relations. China has been in surplus for a long time, and EAC in deficit; most of EAC’s exports to China are primary products and natural mineral resources; most of China’s exports to EAC are labor-intensive industrial products; the import trade links between EAC and China are weak; and the export trade links are relatively close.

From our findings, a lot of efforts need to be put together on both sides especially EAC by improving the productive capacity in order to consolidate in trade intensity, optimizing the trade structure of the two parties and make use of the cooperation platform the “Belt and Road” initiative. However, the import and export intensive index betwixt the two parts shows a rising trend year by year, and the future trade development tendency is better.

5.2. Recommendations

The government of the EAC countries should reinforce the economy of their countries by boosting the trade, investment in the industries which can produce things in order to export and increase the balance of trade because the EAC countries have a negative balance of trade. It can also privatize or semi-privatize some public industries which are crushing, it will help the country to boost the production and to increase the societies.

The unity is something powerful and positive between the countries when they are in a group, the EAC countries should be too united in order to develop the community. The powerful and strong countries in the EAC can help the weak ones to improve their economy or in a weak field.

To reinforce the cooperation between EAC and China, the EAC and China need to have good friendship relations that already exist, and others things will follow. When there are some Chinese projects, companies in the EAC countries, should employ in their companies more citizens of the EAC because the project should create the employment in the EAC’ states.

List of Abbreviations

ACT: Artemisinin-based Combination Therapy (ACT)

AfDB: African Development Bank

ASEAN: The Association of Southeast Asian Nations

AU: African Union

BRI: Belt and Road Initiative

BRICS: Association of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa

COMESA: Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa

EAC: East African Community

ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States

EU: European Union

FDI: Foreign Direct Investment

I&CP: Infrastructure and Capital Projects

MFN: Most Favored Nation

RCA: Revealed Comparative Advantage

SADC: Southern African Development Community

SEZ: Special Economic Zone

TAZARA: Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority

UAE: United Arab Emirates

WTO: World Trade Organization